In the 70s and 80s many a Bar general meeting was given over to motions that the Barristers Board Examinations be discontinued. Members of the Dark Side who introduced the motion would argue that the examinations were not rigorous enough to qualify the student for admission to the Bar. The supporters of the Board Examinations argued to the opposite effect.

The examinations had existed for decades. The Board appointed examiners in the various areas of study which, under the Barristers Board Rules, were considered necessary for the student-at-law (those who were enrolled in the course or some part of it) to qualify for the Bar.

Prior to 1936, degrees in laws were not available in Queensland so those who wished to practice at the Bar had either to seek an appropriate degree interstate or complete the Bar Board Exams. Luminaries such as the great Dan Casey, Justice Kevin Ryan and Justice Kiefel all qualified for the Bar through the Board Exams. Justice Graham Hart and Mr Rex King QC, for example, relied upon interstate degrees.

Each time the motion was argued at general meetings those opposed to discontinuing the exams would mention Dan Casey’s admission through them. Subsequently, Susan Kiefel’s name was added as an example of the course’s alumnae.

At the final meeting Darth Vader from the Dark Side took the initiative of mentioning “Casey” before it was raised in order to reduce the impact which that reference had on members and argued that it was no longer to the point to “embrace the corpse of Casey” to support the retention of the course. Luke Skywalker who supported the retention said in reply that he did not intend to embrace the corpse of Casey but he should like to spend a little time with the warm pulsating body of Kiefel. The motion was put and was once again lost.

At the final meeting Darth Vader from the Dark Side took the initiative of mentioning “Casey” before it was raised in order to reduce the impact which that reference had on members and argued that it was no longer to the point to “embrace the corpse of Casey” to support the retention of the course. Luke Skywalker who supported the retention said in reply that he did not intend to embrace the corpse of Casey but he should like to spend a little time with the warm pulsating body of Kiefel. The motion was put and was once again lost.

Members from the Dark Side then turned their attention to Bar Board Meetings. A motion to discontinue the exams was proposed. All silks were ipso facto members of the Board but no more than three or four ever attended. The normal attendance at meetings including the Judges’ representative and those from the Bar was about six.

When the motion was argued a bevy of silks, most of whom would hardly have known where the Board normally sat, attended. The room was full. The motion was passed by a small majority. Theoretically then, the exams were to be discontinued.

The judges had the last laugh. The Board owed its existence to Rules of Court agreed upon by the Judges. The exams were conducted pursuant to those rules. To discontinue the exams would require a rule change. It was no secret that only some of the judges favoured their removal. No directions were given as to their termination and no rule change occurred. Students-at-law went merrily along enrolling and sitting for the exams to qualify for the Bar. Finally after several years, directions preventing students from commencing the course were given. All those in the system were allowed to continue.

Even after the passing of that “on going” legislation “The Legal Profession Act 2004”, students were using the Board Exams to qualify to be admitted as legal practitioners. As a matter of record, the applicant Rebecca Clifford (Application 1384/07 heard on the 19 March 2007) relied upon her Board qualifications for admission. Indeed, there may still be some to come.

James Crowley QC

Discuss this article in the Hearsay Forum

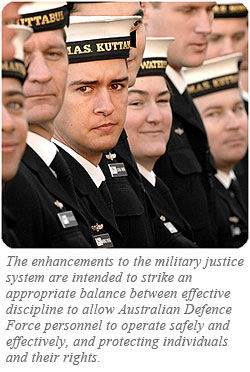

The Australian Military Court replaces the system of individually convened trials by Court Martial or Defence Force Magistrate. The court will be a ‘service tribunal’ under the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982. It is an important part of the military justice system, which contributes to the maintenance of military discipline within the Australian Defence Force.

Establishing the court is one of many reforms to the military justice system. The enhancements ensure a modern and effective approach to military justice, while striking an appropriate balance between effective discipline to allow Australian Defence Force personnel to operate safely and effectively, and protecting individuals and their rights.

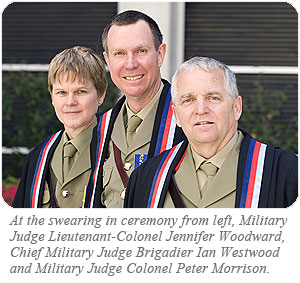

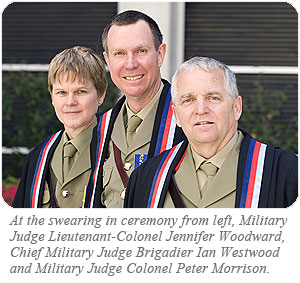

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence.

Brigadier Ian Westwood AM was sworn in as the first Chief Military Judge at a ceremony in Canberra on October 3. He has 24 years of military law experience gained through full-time Army service. He was admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1978 and appointed to the Australian Army Legal Corps in 1983. Brigadier Westwood, who resides in Canberra, is responsible for ensuring the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the Australian Military Court and managing its administrative affairs. He will also sit as a military judge on the court and report to Parliament annually through the Minister for Defence.

Two permanent military judges, Colonel Peter Morrison and Lieutenant Colonel Jennifer Woodward were also sworn in. Colonel Morrison, hailing from Townsville, has a combination of private and military legal experience spanning more than 26 years. He was a Judge Advocate and Defence Force Magistrate prior to his appointment.

Lieutenant Colonel Woodward was previously a senior prosecutor for the Australian Capital Territory and a commercial litigation practitioner. Prior to becoming a military judge, she was Director of Advisings, General Counsel Branch, Department of Defence. Lieutenant Colonel Woodward also spent seven years as a permanent legal officer in the Army.

At the swearing in ceremony, Chief of the Defence Force Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston said Defence was strongly demonstrating its commitment to improving the military justice system and delivering impartial and fair outcomes through enhanced oversight, greater transparency and improved impartiality.

“Since the beginning of my tenure as Chief of the Defence Force, I have been absolutely delighted with the progress we have made to our military justice system,” he said.

“It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.”

“It is critical to the Australian Defence Force’s operational effectiveness and the protection of individuals and their rights that we have a strong military justice system — one that not only underpins our discipline and command structures but also enables our personnel to work in a fair and just environment.”

The new court is judicially independent from the military chain of command and Executive and, although based in Canberra, is fully deployable and able to conduct trials within Australia and overseas, including operational areas.

The Australian Military Court has the same jurisdiction as Courts Martial and Defence Force Magistrates did previously. It only exercises jurisdiction under the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 where proceedings can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purposes of maintaining or enforcing discipline. The Australian Military Court meets the disciplinary needs of the Australian Defence Force in maintaining and enforcing Service discipline by trying more serious or complex Service offences.

How does it work?

As well as the Chief Military Judge and two permanent Military Judges sworn in recently, there will be a panel of part-time (Reserve) military judges. Military Judges are independent from the military chains of command and Executive in the performance of their judicial functions. They may sit alone or with a military jury. Military jurors perform a role akin to jury members in a civilian court system and determine on the evidence whether an accused person is guilty or not guilty of the Service offence.

Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.

Essentially, the trial procedures of the Australian Military Court are similar to those of civil courts exercising criminal jurisdiction. The general principles and laws of criminal responsibility as provided for within the Criminal Code (Commonwealth) apply in respect of Service offences prosecuted before the Australian Military Court, as do formal rules of evidence. The presumption of innocence to the accused applies as it does in a civil court which means that the prosecution is obliged to prove the case against an accused beyond reasonable doubt.

All prosecutions before the court are conducted through the office of the statutorily independent Director of Military Prosecutions, Brigadier Lynette McDade. This area consists of several full-time and Reserve prosecutors. The Directorate of Defence Counsel Services, led by Group Captain Chris Hanna, arranges legal representation for the accused. The directorate administers the Defence Counsel Services Panel, which contains more than 150 lawyers from Army, Navy and Air Force who are located across Australia. These lawyers are admitted to practise in a State or Territory of Australia and come from various branches of the legal profession.

Colonel Geoff Cameron, who is the statutorily independent Registrar of the Australian Military Court, assists the Chief Military Judge with the administration of the court and discharges statutory functions.

Other changes to the military justice system include introducing rights of appeal from decisions of the Australian Military Court to the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Tribunal (presided over by tribunal members who may be Federal Court, State or Territory Justices or Judges). In the case of the accused it is available on both conviction and punishment or court order. In the case of the Director of Military Prosecutions it is available for punishment or order only. Following the next tranche of legislative changes, an accused will also have the right to elect trial by the Australian Military Court for certain categories of disciplinary offences.

If an accused is found guilty, punishment as provided for by the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 is imposed by the presiding military judge taking into account mitigation evidence, the sentencing principles applied by civil courts and the need to maintain discipline in the Australian Defence Force.

Enhancing impartiality and fairness

Enhancing impartiality and fairness

The selection of the Chief Military Judge and Military Judges was through an independent merit process. They were selected from current qualified Permanent and Reserve Australian Defence Force legal officers and any other person who satisfied the statutory selection criteria.

Key features of the Australian Military Court include:

- statutory appointment of legally qualified military judges,

- security of tenure (10 year fixed terms),

- remuneration set by the Commonwealth Remuneration Tribunal,

- mid-point promotion during tenure,

- the necessary para-legal support to be self administering,

- judges to sit alone or with a jury in the case of more serious offences (military judge presiding), and

- appeals on conviction or punishment to the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Tribunal.

The Australian Military Court proceedings are open to the public except where the Military Judge orders otherwise (for example, if it is contrary to the interests of security or defence of Australia, the proper administration of justice or public morals).

Further enhancements to the military justice system

The Australian Military Court is one of a range of enhancements to the military justice system being introduced by Defence. With the two-year implementation schedule due to finish at the end of this year, Defence is well advanced in putting in place the most significant changes its military justice system has seen in more than 20 years. Twenty-three of the 30 agreed recommendations from the 2005 Senate Report ‘The effectiveness of Australia’s Military Justice System’ are now complete.

Major achievements to date include:

- A new joint Australian Defence Force investigative unit now investigates serious incidents with a service connection.

- There is no longer a backlog of complaints and redresses of grievance due to the additional resources being provided and the hard work of Defence personnel.

- A civilian with judicial experience now presides over Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) Commissions of Inquiries into deaths of ADF members in service or other matters as determined by the CDF.

- The Learning Culture Inquiry Report into ADF Schools and Training Establishments was released in December 2006. It followed the military justice inquiry, which found that some aspects of ADF culture may be related to deficiencies in the military justice system. Action to reinforce ADF culture consistent with core values has reduced the risks of inappropriate behaviour, improved the care and welfare of trainees, and improved the management of minors in particular. More than half of the agreed recommendations are now underway.

For further information about the range of enhancements to the Military Justice System visit, www.defence.gov.au/mjs

Cristy Symington

The taking of security to ensure the appearance of the accused at trial is far older than one might expect. It dates back at least to the early days of ancient Rome. There is a record of bail being taken as far back as about 461 BC.

Just how far back this is, is made clear when it is put in the context of major events of Roman history. It occurred roughly 300 years after the traditional date for the founding of the city of Rome (753 BC), 50 years after the monarch Tarquin the Proud was overthrown to found the Roman Republic and about 250 years before Hannibal and his elephants invaded Italy in the second Punic war.

In the context of the Greeks, this precedent occurs about 50 years after Cleisthenes’ reforms led to the establishment of democracy in Athens (510-508 BC), about 20 years after the failure of the Persians’ last attempt to conquer Greece (Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea — 480-479 BC), before the construction of the Parthenon (447 – 432 BC) and about 130 years before Alexander the Great burst forth to overrun the Persian empire.

In the context of the Greeks, this precedent occurs about 50 years after Cleisthenes’ reforms led to the establishment of democracy in Athens (510-508 BC), about 20 years after the failure of the Persians’ last attempt to conquer Greece (Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea — 480-479 BC), before the construction of the Parthenon (447 – 432 BC) and about 130 years before Alexander the Great burst forth to overrun the Persian empire.

For those interested in Biblical history, this precedent occurred less than 1 generation after Esther saved the Jews of the Persian empire from Haman’s proposed pogrom, at about the same time as Ezra’s visit to Jerusalem in 458 BC and about 16 years before Nehemiah rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem.

This brief review of the setting of this precedent in the context of Rome and Greece suggests 2 points. First, that the practice of taking bail from an accused prior to trial is nearly as old as democracy itself. It may not precede democracy as such a procedure has little role in a tyranny. Secondly, that the procedure was known and used before the occurrence of many significant events of the ancient world that are still within the common knowledge of the modern Western world.

The evidence of bail being taken this early is in Titus Livius’ (Livy in English) book, Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City or History of Rome). Livy was one of the great Roman historians. Born at Patavium (Padua) in about 59 BC, he lived through the fall of the Republic to die 3 years after Augustus in 17 AD. His history consisted of 142 books, 35 of which survive. It is a gripping tale of the rise of Rome from its foundation through, amongst other things, the establishment of the Republic and the 3 Punic wars. In doing this, Livy addresses many matters of interest to lawyers. One of them is the following account of bail being taken from an accused.

The early days of the Roman Republic suffered from heightened tension between the aristocracy (patricians) and commoners (plebeians). One dimension of that tension concerned the complex constitutional structure of Rome.

The early days of the Roman Republic suffered from heightened tension between the aristocracy (patricians) and commoners (plebeians). One dimension of that tension concerned the complex constitutional structure of Rome.

The highest political office of the state was that of consul. The powers of the office were immense and akin to those of a King. The restraints on that power included that there were 2 consuls and elections to the office were held annually. The consuls were patricians.

The plebeians were represented by tribunes, a less powerful office.

One tribune, Gaius Terentillus Arsa, proposed that commissioners be appointed to codify the laws limiting and defining the power of the consuls. The patricians vehemently opposed the proposal arguing that consular authority was checked by the power of the tribunes to bring a former consul to trial for misconduct during the consul’s term of office.

The political conflict led to riots. A champion of the patrician’s cause was a young nobleman, Caeso Quinctius, described by Livy as “a man of action, tall and strongly built, whose physical endowments were enhanced by a distinguished record both as a soldier and a forensic orator.”1 He led attacks that hounded the tribunes out of the Forum and scattered the “mob” “like a beaten enemy”.2

In the face of such aggression, one tribune had strength that his colleagues lacked. Aulus Verginius summoned Caeso to stand trial on a capital charge. One allegation against Caeso turned on the evidence of Marcus Volscius Fictor, a former tribune. He said that his older brother, when recovering from the plague, had come across a riotous group of aristocrats, that a quarrel developed that led to his brother being knocked down by a punch from Caeso and that, subsequently, the brother died as a direct result of the blow.

Tribune Verginius wanted to keep Caeso in custody pending trial. The other tribunes disagreed and ordered him to appear before the Court stipulating that in the event of his non-appearance a sum of money should be pledged to the people. The amount was left to the Senate. It said that it would provide sureties, each for the sum of 3,000 asses. That was a considerable sum. The Senate left it to the tribunes to determine the number of sureties. The tribunes required 10 sureties. Verginius then admitted Caeso to bail.

Tribune Verginius wanted to keep Caeso in custody pending trial. The other tribunes disagreed and ordered him to appear before the Court stipulating that in the event of his non-appearance a sum of money should be pledged to the people. The amount was left to the Senate. It said that it would provide sureties, each for the sum of 3,000 asses. That was a considerable sum. The Senate left it to the tribunes to determine the number of sureties. The tribunes required 10 sureties. Verginius then admitted Caeso to bail.

From this one can see that the process of setting bail was addressed by officers and institutions that we would describe as political rather than legal. Trials in those days were highly political affairs. Our concepts of relevance had little application.

The case is also an early illustration of an accused skipping bail. The night after he was admitted to bail, Caseo fled Rome for Etruria [Tuscany]. That had at least 2 consequences.

First, the trial did not proceed. Caseo’s supporters argued that he had gone into exile. Notwithstanding these arguments, the strong tribune Verginius wished to try Caseo in absentia. The other tribunes did not agree. To this extent, Caseo gained from his flight.

Secondly, at least one of the sureties was compelled to pay up. Caseo’s father “had to sell everything he possessed and leave the city. He found a deserted hovel across the river, and lived there like a banished man.”3 Quite a fall for an aristocrat. Livy does not record Caseo as doing anything to remedy this position. Several years later, his father is still recorded as working on a small farm.

The tapestry of this tale is embroidered by a silken thread. Caseo’s father was none other than Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. The US city of Cincinatti commemorates his name. Livy portrays him as a man of substance, selflessly devoted to the service of the Republic. One indication that this was no ordinary man is that several years after suffering financial ruin, he was elected a consul.

Approximately 3 years after Caseo’s flight, charges were brought against the witness Marcus Volscius Fictor whose testimony was the foundation of the case against Caseo. He was charged with giving patently false evidence about Caseo. Two sources of evidence were relied upon as the basis for the charges. First, witnesses said that the sick brother allegedly attacked by Caseo had never appeared in public from the time that he fell ill and, after lingering for many months, died of consumption. Secondly, other witnesses said that during the relevant period Caseo had been on active service and had not gone on leave. Thus Marcus Volscius Fictor could not have witnessed the events that he claimed to have observed.

Before moving on, one might speculate that at least the second group of witnesses would have been available to Caseo to call at his trial. His flight may thus reflect his apprehension that the outcome of his trial before the people would be determined by the political climate of the day rather than the merits.

This prosecution was explosive politically. It could be seen as patrician revenge for the plebeian assault on Caseo. The tribunes delayed the prosecution for political reasons. They refused to allow it to proceed unless the patrician controlled Senate allowed debate on the proposal to codify the powers of the consuls. The Senate steadfastly refused to do this.

This impasse was not the only source of tension for the Republic. Foreign relations were creating their own pressures. Rome was attacked by one of its neighbours, the Aequians. The military situation became critical when the enemy surrounded at Algidus an army commanded by one of the 2 consuls.

To deal with the potential military disaster, the Senate decided to appoint a dictator. As the title suggests, this was an office attended with absolute powers that were not subject to appeal. A dictator could act free of restraint by the consuls or tribunes. Such appointments were made usually for a specific time or purpose.4

The Senate chose Cincinnatus for the office and its envoys found him at work on his 3 acre farm. As we have seen above, he was living in such circumstances because he had gone surety for his son, Caseo. The scene is commemorated by the oil painting by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696 — 1770) that is now exhibited in the Hermitage and by the work by Alexandre Cabanel (1823 – 89) [see illustration]. Cincinnatus accepted the appointment, led a forced march by another Roman army and surrounded the Aequians who were themselves encircling the consular army. The ensuing battle led to the surrender of the Aequians.

When Cincinnatus returned to Rome he celebrated the triumph that the Senate had granted him. The thread he wove in this tale and the story of Rome is silken for he was appointed Dictator twice and each time discharged his duties successfully and then relinquished absolute power voluntarily. For this reason, US citizens like to compare him with George Washington.

When Cincinnatus returned to Rome he celebrated the triumph that the Senate had granted him. The thread he wove in this tale and the story of Rome is silken for he was appointed Dictator twice and each time discharged his duties successfully and then relinquished absolute power voluntarily. For this reason, US citizens like to compare him with George Washington.

This is not to suggest that as Dictator he did not do things that gave personal satisfaction beyond that inherent in serving the general public interest. After saving the consular army by vanquishing the Aequians, Cincinnatus refrained from resigning immediately as Dictator. The trial of Volscius for giving false evidence about the Dictator’s son Caseo was pending. The tribunes who had blocked it were so in awe of the Dictator that they did not continue to impede the proceedings. Volscius was found guilty and sent into exile. Cincinnatus then resigned. This process did not take long — Cincinnatus was Dictator for only 15 days before he resigned! One has to be sceptical about how fair was that trial by our standards.

There is a further twist to the tale which might be expected given the conviction of the accuser Volscius. Caseo returned to Rome without his trial being resumed. So the first recorded instance of bail being granted in ancient Rome had the accused skip bail yet return without facing a trial or a conviction recorded in his absence. While this account suggests that some things used in the present are taken from the distant past, hopefully this part of the historical precedent has been left firmly in the past.

Andrew Lyons

To comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum, click here.

Endnotes

- Livy (translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt); The Early History of Rome; Penguin; p. 196

- Ibid, p. 196.

- Ibid, p. 199.2.

- It was Julius Caesar’s appointment as dictator perpetuus (dictator without term) that gave the impression that he had lost interest in restoration of the republic prompting his assassination in 44 BC.

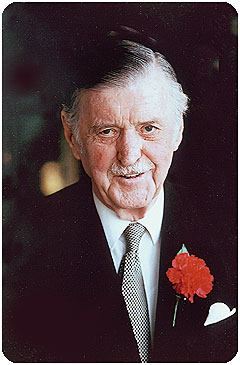

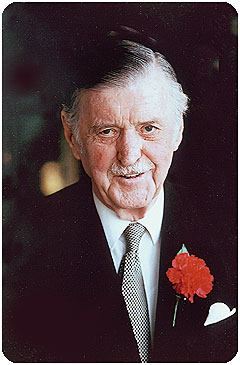

After Sir James Killen’s funeral I was talking to Archbishop Bathersby who remarked that there would never be another service in Queensland like that one. I had to agree. The present Governor-General, the Prime Minister, three former Prime Ministers, two former Governors-General, the Queensland Governor, the Premier and Deputy Premier, the Minister for Defence, members of the Federal Senate, the head of the Defence Force, Church leaders and leaders of Industry, Supreme, Federal and District court Judges, lawyers and other friends in their hundreds all attended. The congregation overflowed into the grounds of the Cathedral and onto the footpath in Ann Street. There is no possibility of a repetition of such a gathering.

A member of the Bar told me that he admired Killen because Killen always recognised him and spoke to him. That is a common response. That was his style. To walk down the street with him was an experience. He would be stopped every twenty metres with people wishing him well. They all loved him. He had a rugged face and a typical Air Force moustache which made him instantly recognisable. He was regularly sought for comment in newspapers and on television. He had a very public profile. His image was a “household word” one might say.

A member of the Bar told me that he admired Killen because Killen always recognised him and spoke to him. That is a common response. That was his style. To walk down the street with him was an experience. He would be stopped every twenty metres with people wishing him well. They all loved him. He had a rugged face and a typical Air Force moustache which made him instantly recognisable. He was regularly sought for comment in newspapers and on television. He had a very public profile. His image was a “household word” one might say.

He entered Parliament in 1955, finishing his degree in law whilst a backbencher and was called to the Bar in 1964. His career at the Bar was interrupted by his ministerial life. In the early days when only a backbencher, he did a bit of everything but probably mostly crime. His compassion was always evident. He had done it tough as a lad, and when about 15 he ran away from Brisbane Grammar School. He went west and became a jackeroo. That experience shaped his later life and nurtured the common touch and generosity of spirit for which he became noted.

He enjoyed an early triumph at the Bar. It occurred when his client was charged with obscene language. The defence was that the language was not the defendant’s but his parrot’s. It had learnt a few obscenities in the course of a long life. When it came to the defence case Killen tendered the parrot. It obliged with some ill chosen words and the complaint was dismissed.

His peers at the Bar, in the early days, treated Killen with mild amusement. Many took the view that his kind of advocacy belonged more to the other place. Yet he was successful in a variety of actions, so Judges and juries must have seen him differently.

His peers at the Bar, in the early days, treated Killen with mild amusement. Many took the view that his kind of advocacy belonged more to the other place. Yet he was successful in a variety of actions, so Judges and juries must have seen him differently.

When he obtained a Ministry his legal pursuits ceased, but after his retirement from Parliament in 1983 he was back at the Bar in all his glory. Pleas of guilty were his forté. His submissions were irresistible. Courts were delighted to note his presence. Magistrates were mesmerised by him. I led him for the Plaintiff in a medical negligence case in the early 1990’s. The trial Judge welcomed him and remarked that it was wonderful to see him back before the court. An appearance in the Court of Appeal a few years later brought a similar response.

His career in politics was stellar. The Defence Ministry suited him admirably and he was on top of his portfolio. Prior to 1976, hundreds of officers had been commissioned but their commissions had not been prepared, some had been waiting since at least 1968. Jim arranged that all commissions be executed and distributed. This may not be a particularly important matter but several ministers before him had not managed it.

An important accomplishment was the purchase of the FA18 aircraft. The competition had been between the famous “Tomcat” (the F15) and the other. The Tomcat was a super fighter plane, and when your force had plenty of heavy aircraft as well, it was tops. Australia needed something with a bit of both types, a fighter and a bomber and so Jim made his choice. It was the largest purchase, in monetary terms made by Defence to that time — hundreds of millions of dollars. MacDonnell Douglas showed its appreciation by giving Killen a neck tie. Modern politicians should take note!

His repartee in Parliament is legendary. but a litany of stories is not appropriate here. One should be retold. Brian Toohey the Canberra journalist had raised hackles in Parliament by a particular report. Killen commented that in his experience Mr Toohey, “could not be relied upon to report accurately a minute’s silence”.

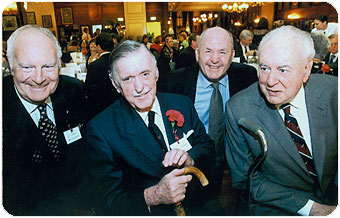

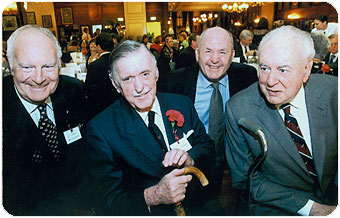

He had a wonderful eightieth birthday party at the Irish Club. Gough Whitlam spoke and so did Alexander Downer. Gough was Gough of course, and Downer’s words were marvellous, yet he had not been in Parliament with Jim. Downer climbed off a plane from Korea, came to the Club, made the speech and was off again. Others spoke too, the Irish Pipe Band played, Irish Dancers danced and Brian Nason added a touch of Australiana with “The Man from Snowy River”. (Tony Morris was late). It was the best night.

He had a wonderful eightieth birthday party at the Irish Club. Gough Whitlam spoke and so did Alexander Downer. Gough was Gough of course, and Downer’s words were marvellous, yet he had not been in Parliament with Jim. Downer climbed off a plane from Korea, came to the Club, made the speech and was off again. Others spoke too, the Irish Pipe Band played, Irish Dancers danced and Brian Nason added a touch of Australiana with “The Man from Snowy River”. (Tony Morris was late). It was the best night.

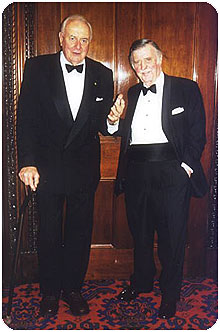

Lord Denning ranked amongst his friends. Denning inscribed the first of his quintet of autobiographical tomes for Sir James. George Bush senior also shared his friendship. James had flown in US Air Force 2 when Bush senior was Vice President. He was a close friend of several members of the Dixon & Barwick Courts, especially Barwick, Menzies and Taylor. One might perhaps feel that Killen related best to the “larrikin” element on the Court.

Lord Denning ranked amongst his friends. Denning inscribed the first of his quintet of autobiographical tomes for Sir James. George Bush senior also shared his friendship. James had flown in US Air Force 2 when Bush senior was Vice President. He was a close friend of several members of the Dixon & Barwick Courts, especially Barwick, Menzies and Taylor. One might perhaps feel that Killen related best to the “larrikin” element on the Court.

He was a favourite for eulogies and his contribution was always full of generosity and warmth. He delivered the eulogy at the funerals of Sir Garfield Barwick, Senator Neville Bonner and General Sir Arthur McDonald and at so many others that there hardly seemed a week pass, that he was not at a funeral. He said he would have to start charging appearance money. I attended with him on several occasions. He sang lustily and was staunchly devout. It was part of his spiritual life. Worship was important to him.

His charity of thought and speech was signal. I would rail against someone for a gross breach of decorum. He would excuse the breach by saying it was mere “social exuberance”. Criticism was not in his makeup no matter how blatant the offensive behaviour.

He was asked incessantly to give references or to intercede for friends or friends of friends. He lent his help generously and his intercessions were always with sincerity and concern. He received a torrent of mail from people seeking his help. He was forever phoning or writing to Officials. Organisations as diverse as the Border Collie Club of Queensland, the Queensland Jockeys Association, the 139 Club and the Guards Association proudly boasted his patronage. There were others. He had thousands of friends and was loyal to them. They reciprocated.

He liked to talk of his appearance in the High Court in Anderson v Liddell & Ors [1968] 117 CLR 36. He was but a callow junior and was opposed by the august Sir Arnold Bennett QC leading Alan Demack. He did not win but from his description I gather Sir Arnold had some worrying moments. In another High Court matter, Killen was led by Senator Condon Byrne so political logic (if there is such a thing) would have been much to the fore. He related how the members kept stopping Byrne and conducting discussions between themselves. When it came to 4.30pm Dixon CJ asked how long Byrne expected to be the following morning. “A further hour,” was Byrne’s response. “That long?” responded the Chief Justice; “of course we’ve been interrupting you.” “Not at all Your Honour” was Byrne’s reply. “We had the distinct impression that we were interrupting the Court.”

He loved horse racing. He was not a big punter but he was a dedicated one. Over the years he owned a number of horses with Eddie Broad (later Judge Broad) and his great friend Jim Kennedy. For years he went to Melbourne for Derby Day and the Melbourne Cup, but unlike a certain Bob Douglas (sadly now deceased) he sometimes backed a loser.

He sat on the Racing Appeals Tribunal for some years in the late 1990s and early this century. Mr Leo Williams was Chairman and Mr Dennis Standsfield the second member. Sir James was a “softie” when it came to penalising owners, trainers etc. The other Tribunal members had to keep a tight rein. He would tell me of the hearing and when referring to the penalty would invariably add “The poor beggar”. One greyhound owner said he had his dog in the car and would like to bring it into the court. “You would get on well with him,” he told Killen, “you have similar personalities”.

He sat on the Racing Appeals Tribunal for some years in the late 1990s and early this century. Mr Leo Williams was Chairman and Mr Dennis Standsfield the second member. Sir James was a “softie” when it came to penalising owners, trainers etc. The other Tribunal members had to keep a tight rein. He would tell me of the hearing and when referring to the penalty would invariably add “The poor beggar”. One greyhound owner said he had his dog in the car and would like to bring it into the court. “You would get on well with him,” he told Killen, “you have similar personalities”.

He was one of the Government’s nominees at the Constitutional Convention in February 1998. His address followed Mr Neville Bonner’s (formerly a member of the Senate). Bonner ended with a chanted lament. The effect was electrifying. He received a standing ovation with prolonged clapping. To follow him was a challenge which few could have successfully accepted, but Sir James was equal to the task. With supreme sensitivity and judgment he first took the Bonner theme, continued it for a little, (he must have composed this on the spot) then turned to his own thoughts which were delivered (as was common for him) without notes. It was a superb effort.

Much time was taken up on the lecture circuit. He delivered “A Reflection”, the R D Sherington lecture in 1994, “Humanity & Technology: “Where is the Master”, the David Boughen Memorial Lecture in 1995, “Our Fragile Liberty”, at the Conference of Prison Chaplains in 1996, “Is Parliament Expiring”, the Professor Tess Brophy lecture in 1996, “A Passing Shadow”, the Churchill Lecture in 1998 and “Speech is of Our Time”, the Dr Allan Martin lecture in 1999, to name but a few. He took enormous pride in researching the topics and delivering the lectures. Nothing less than a perfect performance would suffice.

After his return to the Bar we had a civil jury trial acting for the Plaintiffs and Killen knew one of the jurors quite well (you could not have drawn a panel without him knowing someone on it). I asked Killen how he knew him, “From the races” was his reply. I asked what he did, “He’s tied up with Insurance”. “What the hell did you let him on for”, I asked, a bit annoyed. “Well he’s good with figures and we need someone to divvy up the damages”.

Killen fired another bon mot in the course of that trial. Ron Ashton was on the other side and when he turned up early one morning (a novel event for Ron), Killen said, “Good morning Ron, that is a wonderful organisation you run”. Ashton not unnaturally and in the context of legal affairs took the remark as a reference to Minter Ellison, where Ron was the Managing Partner, and thanked Jim for his remark, “Yes” Killen continued, “They came and changed a tyre for me yesterday”. Ashton was President of the RACQ at the time.

Des Draydon when a member of the Inns 20th level (where Killen had chambers) organised a party for Jim’s 70th Birthday. It was held at the Guineas Room at Eagle Farm with a star studded cast. Whitlam and John Gorton both spoke beautifully of this character who was gracious to all and loved by all. Joy, his first wife, also spoke. Draydon thoughtfully called the occasion “A Knight of no Divisions”.

The Bar’s sympathy is extended to his wife Benise, to his daughters Diana and Heather and to his sister Dawn. DENIS JAMES KILLEN AC KCMG, the knight of no divisions, will be missed by all.

James Crowley QC

To comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum, click here.

Examination in chief is not the most important part of a trial; your opening address is, in my view, the most important. Examination in chief is not hardest; cross examination is the hardest. It is not the most fun, your closing address is the most fun. Unfortunately, examination in chief is necessary if you are to put on a prima facie case or a good defence. Sadly, the principal feature of examination in chief is that it is boring.

Examination in chief is not the most important part of a trial; your opening address is, in my view, the most important. Examination in chief is not hardest; cross examination is the hardest. It is not the most fun, your closing address is the most fun. Unfortunately, examination in chief is necessary if you are to put on a prima facie case or a good defence. Sadly, the principal feature of examination in chief is that it is boring.

Courts have responded to this by increasingly replacing live examination in chief with affidavits and statutory declarations for percipient witnesses and reports for experts. Despite this trend, there are still many occasions where we have to lead a witness in our case and conduct examination in chief. This brief article, and next month’s will suggest some techniques to make this necessary evil as effective and interesting as possible. This month we will focus on the witness’s role and next month on your role as the examiner.

As a barrister your job is to orchestrate the witnesses who will be telling your client’s story while being as interesting as possible. Except in the most unusual matter, where you have a case with sex appeal and engaging witnesses, it will still be, despite your best efforts, boring. Many lawyers make it even more boring by using formal language, incantations, stupid questions, and poor use or non-use of demonstrative evidence.

In America we spend a great deal of time preparing witnesses. While that practice is far more limited here, some preparation is both proper and necessary.

A brief anecdote will illustrate the need for at least agreeing with your key witnesses on what you will be doing. The scene is a criminal court in the US, the case is murder. The case against the defendant is circumstantial, but compelling. The prosecution’s major obstacle is the lack of a body – the police never found the body of the victim. The prosecution evidence has gone in and it is damning, despite the lack of the body. The lawyer for the defence has put on no witnesses and it is time for closing arguments. He is left with only one issue: reasonable doubt.

A brief anecdote will illustrate the need for at least agreeing with your key witnesses on what you will be doing. The scene is a criminal court in the US, the case is murder. The case against the defendant is circumstantial, but compelling. The prosecution’s major obstacle is the lack of a body – the police never found the body of the victim. The prosecution evidence has gone in and it is damning, despite the lack of the body. The lawyer for the defence has put on no witnesses and it is time for closing arguments. He is left with only one issue: reasonable doubt.

He stands to address the jury:

“Ladies and gentlemen, I have a surprise for you, in exactly one minute the alleged victim, the alleged decedent, will walk through the doors of this court room.”

He looks conspicuously at his watch. The jurors all swing their heads and stare intently at the doors of court. Silence is total. A minute creeps by. Nothing happens. The lawyer again addresses the jury:

“Ladies and gentlemen, I hope you will forgive me, I actually had no idea whether or not the decedent would walk through the doors of the court room. But I want you to note – each and every one of you looked at the doors. That means you must have held some doubt, some reasonable doubt, that he was in fact dead, and thus under the law you must acquit my client.”

The judge instructs and the jury goes to deliberate. In 10 minutes they’re back.

“Ladies and gentlemen have you reached a verdict?”

“We have your Honour.”

“What is your verdict?”

“Guilty”

The defence lawyer is shocked. After the defendant is taken away and the court is in recess, the lawyer goes to chat with the jurors as is permitted in the United States once the case is over.

“What happened? You all looked.”

“Yes we all looked… but your client didn’t.”

A lot of preparation will frankly be useless, witnesses often ignore instructions and advice, but some things should still be done. First and foremost, witnesses should be cautioned to tell the truth. They should be told not to worry if they think an answer might harm their case; a lie will be far worse and the answer may not be as harmful as they might think.

They should be told that you cannot ask leading questions and thus they need to be prepared to tell a story in narrative form, a few sentences at a time.

If there is a jury, they should turn toward the jury for all but the briefest answer, or toward the judge if the trial is to the court alone.

Your question should be of the form “Tell the ladies and gentlemen of the jury about…” or “Tell her (or his) Honour about..”

In the increasingly rare case where you are leading a technical or expert witness in examination in chief be sure they are told to avoid the mealy mouthed qualifications that doctors and scientists so often use. If they are morally certain of their diagnosis or opinion they should avoid the caveats they might put in their journal article as any equivocation will be exploited by the other side.

Likewise they should carefully explain, in layman’s terms, any special concepts or technical vocabulary. This is particularly important where a scientific or technical opinion might be counter-intuitive to a judge or juror.

Some other points:

Some other points:

- Don’t rehearse or insist on pat phrases. Apart from the obvious ethical issue, it makes witnesses sound implausible if they respond to questions with repeated pat answers.

- Agree on a stop sign, perhaps a raised hand, so you can interrupt a narrative that is going on too long or going off track.

- Alert them to the possibility of objections, and that they should stop speaking and look to the court for direction after an objection.

- Tell them that they should not guess or speculate.

- Tell them also that they should not give evidence about things outside their personal knowledge.

- Remember that a nervous witness might be taken to the court in advance to watch an unrelated matter, to see the setting and get a feeling for how things proceed.

Witnesses also need to be told about the prospect of cross-examination. This is a good time, again, to remind witnesses to tell only the truth. That said, witnesses should not allow fear or deference to the cross-examiner to allow them to be lead to agree with a proposition of fact that they do not fully agree is true.

In addition witnesses should be cautioned not to modify their body language or attitude when the questioning shifts from you to the cross-examiner. An open aspect and friendly attitude should not become a closed, defensive posture (arm crossed tightly across the chest, for example) and terse mono-syllabic answers. Answers should be brief, and limited to the question, but spoken in the same friendly, open manner as when under examination in chief, regardless of the demeanor of the cross-examiner.

Witnesses should be reminded to give up bad stuff, what they might think of as adverse information, if the proper question is put. Witness should be told not to be evasive, as that often can cause more harm than a truthful answer.

Witnesses must be instructed to listen to the questions carefully, and ask the examiner to repeat or re-phrase if the question not clearly heard or understood. Likewise witnesses must be told to wait for the examiner to fully complete the question before attempting to answer, and to pause just briefly to allow time in case you have an objection. Witnesses should give short, honest answers and stop when the question has been answered. They should never volunteer information – they should not answer a question that no one has asked.

Let’s now talk about what witnesses we will call, to the extent we have a choice. Working with the instructing solicitor, think about selecting witnesses. There are three types of witnesses.

- Witnesses you need to make your prima facie case or establish your defence. You are stuck with these. Unfortunately these are usually the least articulate, least credible or most boring, but you have to use them.

- Witnesses whom you don’t need for your prima facie case or defence, but help your theme or theory. These might include expert witnesses to the extent current rules or court practice permit a party having its own experts. Experts may also be a witness you need, but in most cases the identity of the expert is not fixed – your team may have some options on which expert to engage. With current practice limiting expert testimony to reports this may not provide much benefit, but the expert might be able to re-enforce his opinions during cross-examination, particularly if the cross-examiner is not skilled. Experts might be the topic of a separate article in this series.

- The third type of witness is one who is not strictly necessary but is one that the judge or jury will like and identify with – doesn’t matter what they’ll say. This requires some imagination so they are not excluded as irrelevant. In a criminal case these might be character witnesses, for example. The point of these witnesses, particularly in jury trials, is to establish rapport between your side in the jury. If you lead witnesses the jurors can identify with, they are more likely to identify with your client.

Finally, for this month, let’s look at one typical problem witness – the smart arse.

The other problem witness is the smart arse. He or she (though far more often he) knows more than you, more than the other lawyers and has an attitude about the courts, the judicial system and, in particular, the case at hand.

These witnesses are likely to try to prove themselves more clever than the lawyers and usually inflict great harm on themselves and their cases. They are very, very hard to control. The only technique that I have had any luck with is boost their egos by telling them how they are the real experts in whatever it is they do in life, but despite their vast legal knowledge gained from watching LA Law, that they might be well served to follow your advice when it comes to what to do in court.

You can expand on that by saying that the other side will expect them to argue and make inappropriate comments and thus self-destruct, but that the witness is far too clever for that and so will take your advice on how to answer questions and behave in court. That said, good luck, they will still blow up at least half the time and if you somehow avoid having them give evidence at all that is by far the safest course.

Next month we’ll talk about the actual questioning of the witnesses you are leading and how to make the most of what you have.

Peter Axelrod

To comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum, click here.

Superannuation is one of the most effective savings vehicles available and the Simpler Super changes taking effect on 1 July 2007 are set to increase the attractiveness of super even further.

However, many Australians are not fully aware of the changes taking place. A recent survey by Mercer1 indicates that 70 per cent of working Australians over 50 years of age cannot articulate any of the Simpler Super changes.

Members of super funds need to understand how the Simpler Super changes will effect them, both before and after 30 June 2007, so they can make immediate changes to their super arrangements and benefit from the opportunities that exist now, and to optimise their financial planning over the longer term.

The tax-free super window

Between 10 May 2006 and 30 June 2007 the Government will give you a one-off opportunity to contribute up to $1 million of after-tax money to super.

While Simpler Super changes mean withdrawals from taxed super funds become tax-free for those over 60, it is always recommended that members seek expert advice when considering making additional contributions or converting non-super assets into super in the lead up to the changes.

The $1 million opportunity has already had a significant effect on contribution levels. legalsuper can report that member contributions in the 9 months ended 31 March 2007 have increased by a factor of three over the same period as last year.

The $1 million opportunity has also lead to growth across all types of super funds and in particular in Self Managed Super Funds (SMSFs, also known as ‘DIY Funds’).

While SMSFs may be appropriate for some, many experts are advising caution because of their inherent complexities, costs and limitations, a point recently underlined in a joint statement issued by the Australian Tax Office and Australian Securities & Investments Commission, which observed that:

“…you need around $200,000 in super to make the costs of a SMSF worthwhile…[W]ith less than this amount, the fund may have difficulty earning enough to make set-up and running costs worthwhile. SMSFs can typically cost around $1,700 to run each year, and quite often cost more.”2

Recognising the interest Australians have in investing in shares, some non-SMSFs are now offering investment options that give members greater control over where their super is invested without the added burden of administration and compliance. Options like legalsuper’s ASX 200 option let members invest up to 50 per cent of their super in ASX200 companies.

Contributing to super after 1 July 2007

Arguably the biggest change under Simpler Super is that withdrawals from a taxed super fund (such as legalsuper) will be completely tax-free after age 60 — whether paid as a pension or lump sum.

However, the Federal Government has also introduced limits on how much people can pay into super, including limits for after-tax and before-tax contributions.

After-tax contributions (now known as ‘non-concessional’ contributions)

After-tax contributions (now known as ‘non-concessional’ contributions)

From 1 July 2007 the maximum personal after-tax contribution will be capped at $150,000 per year, although three year’s worth — $450,000 — can be put in at once.

The sting in the tail is a 46.5 per cent tax on any after-tax contributions that exceed the cap.

Before-tax contributions (now known as ‘concessional’ contributions)

Before-tax contributions include superannuation guaranteed contributions, salary sacrifice contributions, and personal contributions claimed as a tax deduction by self-employed persons.

From 1 July 2007 there is a cap of $50,000 per annum for before-tax contributions. The existing aged-based limits will be abolished from 1 July 2007.

For Australians aged 50 and over, the cap has been increased to $100,000 per annum between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2012.

Before-tax contributions above in excess of the $50,000 cap will be taxed at 46.5 per cent, including the existing 15 per cent tax levied upon super funds.

For Australians aged 50 and over, the cap has been increased to $100,000 per year between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2012.

What all this means is that in future it will limit the possibilities for Australians to ‘top up’ their super at the last minute before they retire. Rather, Australians will need to start saving earlier and build their super over a longer timeframe. It is anticipated this will encourage Australians to take a longer-term view of their retirement planning.

Andrew Proebstl, Chief Executive, legalsuper

Andrew Proebstl, Chief Executive, legalsuper

legalsuper is a not-for-profit, no-commission super fund that returns all profits back to members.(www.legalsuper.com.au)

To comment on this article in the Hearsay Forum, click here.

Endnotes

- Mercer Wealth Solution’s Simpler Super Study, May 2007

- ‘Is self managed super right for you?’ published by the Australian Taxation Office and Australian Securities & Investments Commissions, May 2005

The Junior Bar

Welcome again to the Junior Bar Report.

As you may recall, Queensland barristers of not more than five years standing were recently invited to participate in a web survey in relation to pupillage.

I am delighted to report that around 75% of the Junior Bar responded, which is a fantastic proportion. Of those that responded, well over half provided further comments in the space provided at the end of the survey. Indeed, there are 11 pages of comments in total and every single comment is thought-provoking in some way. The responses are currently being broken down into bar and pie charts and will be ready for presentation in next month’s edition of Hearsay. I am sure that they will prove to be of great interest not only to the Junior Bar but to the Bar as a whole.

As part of my role on the Bar Council, I was recently asked to deliver a short presentation during Law Week about going to the Bar. It was very well well-attended and the audience had a number of questions and seemed genuinely interested about a career at the Bar. Having said that, one or two people did get “off-topic” and asked how barristers could live with themselves defending criminals everyday. I tried my best to highlight the respective roles of the DPP and defence counsel (and the fact that I don’t seem to get a lot of criminal briefs) but the experience underscored for me that the general public still have many misconceptions about the legal profession. Law Week serves a very useful purpose and it is I think important to remember that our legal system is, in reality, underpinned only by the faith that the general community has in it. Events such as Law Week are a real opportunity for the Bar to explain exactly what it is that we do and to encourage the community to “keep the faith”. For that reason, I hope that the Bar Association maintains and strengthens its commitment to Law Week.

If anyone has any topics or issues they would like me to raise in this column then I encourage them to use the Forum or to contact me on crawford@qldbar.asn.au

Chris Crawford

The translation in format, from PDF to Web-page, should render Hearsay even more attractive to the reader or browser.

I commend the Bar Council for its support for this initiative, and Martin Burns and his team for their valuable contribution.

The liveliness of the issues confronting the contemporary barrister more than warrants a publication on this regular and comprehensive basis; and it has the added attraction of being interesting and even, not infrequently, entertaining.

The Hon Paul de Jersey AC

Chief Justice of Queensland

The taking of oaths and the making of affirmations by witnesses in the courtroom are solemn occasions. The avowal of a witness that he or she will tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” is central to the integrity of the evidentiary process. The vow is so serious that a person who breaches it is subject to penal sanction for perjury.

The short ceremony during which the oath or affirmation is administered has traditionally been accorded great respect by all those present in the courtroom. The tradition in Queensland, as in other states and in England, is that strict silence should be observed while this step is carried through. That means that there should be no conversing or shuffling of papers at the bar table while oaths and affirmations are being administered.

The short ceremony during which the oath or affirmation is administered has traditionally been accorded great respect by all those present in the courtroom. The tradition in Queensland, as in other states and in England, is that strict silence should be observed while this step is carried through. That means that there should be no conversing or shuffling of papers at the bar table while oaths and affirmations are being administered.

Members are reminded of the importance of this tradition. It is a mark of our respect for an event which is not mere ritual, but is of great significance to the court and the witnesses.

I f a person is denied committal proceedings, “the accused is denied (1) knowledge of what the Crown witnesses say on oath; (2) the opportunity of cross-examining them; (3) the opportunity of calling evidence in rebuttal; and (4) the possibility that the Magistrate will hold that there is no prima facie case or that the evidence is insufficient to put him on trial …”. (See: Barton v The Queen (1980) 147 C.L.R. 75 at p.99)

Whilst all of the above is undoubtedly correct, it does not follow that in every case oral evidence ought be called at committal nor witnesses cross-examined.

However, it is at committal stage that careful advice must be given to defendants to enable them to understand the options they have as to the future progress of their case and the consequences of the option taken.

This is so because optimum prospects of success at trial usually depend on testing evidence at committal, but equally, the best chance of securing the most favourable sentence for a defendant often involves the deliberate avoidance of oral evidence at committal.

Whether You Should Require Oral Evidence At All?

The answer to this depends upon the case you are dealing with.

If it seems likely that the matter will ultimately result in a plea of guilty in a superior Court, it may well be better to have a full hand-up committal. In some cases, the saving of every skerrick of mitigation, including saving Crown witnesses from the ordeal of giving evidence and being cross-examined at committal, may be the difference between a custodial and non-custodial sentence. Whatever the case, not putting Crown witnesses through committal proceedings should always be taken into account by a Judge in favour of the defendant when determining sentence.

This is so because a hand-up committal goes hand-in-glove with the later plea of guilty. It may demonstrate, at an early stage of the process, remorse and co-operation, and it also achieves a saving to the State. These are significant mitigating factors when it comes to sentence.

Of course, it is often difficult to assess whether or not the matter will result in a plea of guilty. One does not wish to waste mitigation and thereby fail to achieve the most favourable sentence for a defendant, should he subsequently plead guilty, by unnecessarily conducting contested committal proceedings. On the other hand, one does not wish to miss the opportunity of testing relevant witnesses at committal should the matter be going on to trial.

Notwithstanding strong cases against defendants at committal, at that early stage of the criminal justice process, before the reality of the benefits of maintaining every piece of mitigation really hits home for a defendant, some defendants will not even countenance the possibility of a plea of guilty.

Notwithstanding strong cases against defendants at committal, at that early stage of the criminal justice process, before the reality of the benefits of maintaining every piece of mitigation really hits home for a defendant, some defendants will not even countenance the possibility of a plea of guilty.

It is, of course, very difficult for defendants to make these decisions. Some defendants, though innocent, may be tempted to plead guilty and therefore have a hand-up committal in an attempt to secure the most favourable sentence. On the other hand, some defendants may have little prospect of succeeding at trial, but, for any number of reasons, they may insist on contesting committal proceedings and marching on to trial.

A lawyer can do no more than in every case explain to the client in detail the pros and cons of a hand-up committal and the pros and cons of a contested committal. It is then for the client to give instructions in relation to the conduct of the committal.

In cases of multiple charges, a defendant may contest at committal certain charges and not others. If, subsequently, those contested charges are defeated and the defendant pleads guilty to the others, no mitigation will be lost.

In some cases, a defendant may contest the severity of the charge. For example, whilst prepared to plead guilty to assault occasioning bodily harm, the defendant contests at committal the circumstances of aggravation alleged. If, subsequently, the circumstances of aggravation are defeated, the defendant will have lost no mitigation upon a plea of guilty to assault occasioning bodily harm.

Further, a defendant may test evidence at committal with a view to establishing the proper factual basis of the offence for sentence purposes. For example, the defendant may be prepared to plead guilty to dangerous driving causing death on the basis of some speed, but deny that he was travelling anywhere near the speed alleged by the pursuing police.

If ultimately the defendant is sentenced on the basis of the less serious circumstances, then, again, of course, the defendant’s mitigation remains intact.

There are two other considerations at committal stage when looking at securing the most favourable sentence for a client.

Firstly, consideration may be given to whether one should by-pass committal proceedings altogether and consent to an ex-officio indictment.

Firstly, consideration may be given to whether one should by-pass committal proceedings altogether and consent to an ex-officio indictment.

Experience suggests that this course has practical difficulties. Before an ex-officio indictment may be presented, the Crown and defence must be in agreement as to the factual basis for sentence. Logistically, it is often very difficult to achieve this agreement because the Director of Public Prosecution’s office is extremely busy and work must be prioritized. It can happen that it takes longer for a defendant to be sentenced on an ex-officio indictment than if he had proceeded through a hand-up committal.

Experience also suggests that there is not a significant advantage, if any, for the defendant at sentence in proceeding by way of an ex-officio indictment. Consenting to an ex-officio indictment is a clear indication of an early plea of guilty. But, so too is consenting to a hand-up committal followed by having the sentencing Court informed of the plea of guilty on presentation of the indictment.

Secondly, consideration may be given to pleading guilty at the committal proceedings. In my opinion, this course is open to problems. For example, once the defendant is recorded as pleading guilty to the charge it may be difficult to achieve concessions from the Crown as to the factual basis for the sentence. Or, as months pass between committal and presentation of the indictment, a defendant may change his mind as to the plea, prompted by any number of things.

In my view the safer course at committal is to advise the defendant to not enter any plea. Then, upon confirming the intention to plead guilty once the indictment has been presented, the defendant attracts the benefits resulting from an early intimation of a plea of guilty.

There is no doubt that the best chance of securing the most favourable sentence for a client involves careful advice and decision-making at the committal stage.

If it seems likely that the matter is to proceed to trial, the testing of evidence at committal is usually essential to achieving optimum prospects of success at trial.

I say “usually” because there are exceptions to requiring and testing oral evidence at committal, even when intending to go on to trial.

In some matters, for example importation of drugs, the case may depend on incontrovertible circumstances including video and telephone surveillance proving the importation of the package by the defendant. Subject to considerations of testing the validity of warrants, there may be nothing in the Crown case to contest. Rather, the guilt or otherwise of the defendant may depend upon his explanation at trial as to what the telephone conversations really meant and why the package he imported contained drugs. The explanation that he thought the package contained diamonds and not drugs has been done before both with and without success.

Again, in some cases all witnesses for the Crown may be friendly with and sympathetic to the defendant. The defence may take signed proofs of evidence from such witnesses, clarifying and qualifying their Crown statements without the need for committal proceedings. This process has the obvious advantage that the prosecution may not know about the clarifications and qualifications which these witnesses would undoubtedly give at trial.

There are also cases in which a defendant contests the charge but on the face of the police statements there is a hiatus in proof of one of the elements of the offence. If one embarks upon oral evidence, the relevant missing evidence may tumble out. The prosecutor, upon looking more closely at the brief if it is a contested matter, may take the opportunity to augment the evidence in the statements and fill the evidentiary gap. It therefore becomes tempting to have a hand-up committal and then argue on the face of the statements that the charge is not made out and have the defendant discharged at committal. However, the victory may be short-lived. The Director of Public Prosecutions may present an ex officio indictment, having secured the missing evidence. The defendant has then lost the opportunity of testing all of the relevant evidence at committal. If it is demonstrated that a defendant would suffer unfairness in not cross-examining relevant witnesses before trial, a judge would permit cross-examination on a voir dire. However, leaving aside consideration of any Crown evidence obtained after committal, it may not be easy to demonstrate unfairness in circumstances in which the defence made a tactical decision to avoid cross-examining any witness at committal.

The benefits for the defence of requiring oral evidence at committal are substantial:

(a) The defence gets to know precisely the case against the defendant. The witnesses are made to articulate in detail what they claim to have seen and heard etc. and to detail the circumstances in which they say everything occurred. Any shortcomings in what they can say about the matter become apparent. There is far greater clarity to the case than that which is described in police statements.

(b) The defence gets to see the witnesses and learn how they will perform before a jury. One learns whether a witness is likely to be flexible or likely to give no concessions to any suggestion made by the defence. This assists in determining how to cross-examine each witness before the jury.

(c) The defence learns what questions to ask at trial, and, importantly, what questions not to ask at trial. Getting a damaging response to a non-essential question from a witness in cross-examination at committal is generally not harmful to a defendant. The defence knows not to ask that question before the jury. On the other hand, if a Crown witness responds to questions in a way favourable to the defendant, one can ask those questions with safety before the jury. If the witness gives an inconsistent answer before the jury, the person’s answer at committal may be proved.

There are disadvantages for the defence in requiring oral evidence at committal:

(a) The Crown witnesses get something of a dress rehearsal before trial. It is true that some witnesses may suffer a rough cross-examination at committal and therefore be fearful of cross-examination at trial, resulting in their being less dogmatic before the jury. However, often witnesses draw strength from having survived the committal proceedings and are better prepared for cross-examination at trial. Some Crown witnesses may then present better before the jury than they did at committal.

(b) There is the potential that cross-examination at committal may inadvertently enliven a line of inquiry by the prosecution, disadvantageous to the defence and previously unknown to the prosecution.

Notwithstanding disadvantages or potential disadvantages, generally speaking, defendants who are going on to trial should undoubtedly require oral evidence at committal.

The Nature and Scope of Questioning

Questioning is usually quite unconfined (but relevant) and persistent (that does not mean repetitive) since the purpose is to know precisely what a witness will and will not say about the case. However, as referred to above, care must be taken with the questioning not to provoke a valuable line of inquiry for the prosecution. For example, in an assault case, wide cross-examination of a witness to the alleged assault may cause the witness to mention for the first time that the witness saw the defendant involved in an earlier altercation with a person other than the complainant. Or, the witness may mention for the first time that another person, previously unknown to police, also witnessed the alleged assault. The prosecution would no doubt be interested in further proofing the witness as to the defendant’s aggressive demeanour and behaviour during the day prior to the alleged assault and in proofing the other potential witness to the alleged assault.

The defence is not obliged nor expected to, and, in my view, usually should not, put the defence case or any part of it, at committal. No doubt there will be circumstances which justify exception to the rule, but they would be rare. Generally speaking, there is not only no benefit to a defendant, but there is potential damage, in broadcasting at an early stage to the prosecution and the Crown witnesses the defence case or that which the defendant says about certain parts of the Crown evidence. For a start, it gives the prosecution the opportunity to gather further evidence to rebut propositions put at committal. It also alerts the witness to what will be suggested at trial and thereby enables the witness to give a more considered response before the jury.

It is also important to remember that the conduct of committal proceedings can be revisited by the prosecution at trial. If the defence puts a proposition to a witness at committal and a different proposition is put to the witness at trial, the apparent inconsistency in instructions by the defendant to his lawyers can be explored in cross-examination of the defendant at trial.

In circumstances in which the defence believes that it has very good prospects of defeating the charge, permanently, at committal, exposing the defence case may be warranted. For example, having cross-examined a police officer to the point where he asserts without any doubt that the conversation between him and the defendant is the inculpatory conversation which he swears it to be, the playing of an audio tape of that conversation revealing nothing but exculpatory statements by the defendant, could be well justified. It must be remembered that the assessment of the credibility/reliability of a witness called at committal is “a matter which has relevance in determining whether evidence there adduced is sufficient to put an accused person on trial before a jury. One object of testing the evidence of a witness upon committal proceedings is to test the strength of the case brought against the defendant to see if it justifies putting him on trial”. (See: Purcell v Venardos (No. 2) (1997) 1 Qd.R. 317 at p.322)

In circumstances in which the defence believes that it has very good prospects of defeating the charge, permanently, at committal, exposing the defence case may be warranted. For example, having cross-examined a police officer to the point where he asserts without any doubt that the conversation between him and the defendant is the inculpatory conversation which he swears it to be, the playing of an audio tape of that conversation revealing nothing but exculpatory statements by the defendant, could be well justified. It must be remembered that the assessment of the credibility/reliability of a witness called at committal is “a matter which has relevance in determining whether evidence there adduced is sufficient to put an accused person on trial before a jury. One object of testing the evidence of a witness upon committal proceedings is to test the strength of the case brought against the defendant to see if it justifies putting him on trial”. (See: Purcell v Venardos (No. 2) (1997) 1 Qd.R. 317 at p.322)

Questioning of witnesses as to any criminal history and as to matters of credit unrelated to the circumstances of the offence is often productive. Whilst the Crown is obliged to provide criminal histories of witnesses if requested, most witnesses are unaware of this. Sometimes a witness is silly enough to deny any criminal history, or, minimise it. Of course, lawyers must be aware of and comply with Section 15A of the Evidence Act when questioning as to a person’s criminal history. Again, one must be aware of Section 15 of the Evidence Act. If the defence attacks the character of a Crown witness at trial and the defendant gives evidence at trial, the prosecution may seek leave to cross-examine the defendant as to his criminal history.