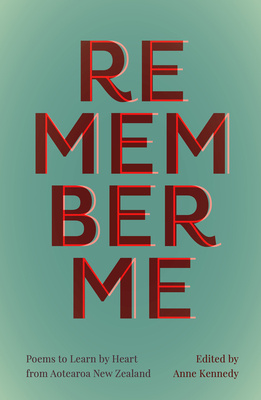

Editor: Anne KennedyPublisher: Auckland University Press 2023Reviewer: David W Marks KC*

- This is not simply another anthology of New Zealand verse.

- The editor, Anne Kennedy, is serious in her intention that you be able to memorise – nay recite – its memorable contents.

- Many notable authors are represented, and even a few old standards.

- Thus, there is an extract from “Home Thoughts”, by that pivotal, South Island figure, Denis Glover. Dismissing thoughts of England, Glover wrote:

I think of what may yet be seenin Johnsonville or Geraldine.

- He thus immortalised two South Island hamlets. The sentiment is also seen in Australian poetry, as we slipped the colonial apron-strings. Thus, Dorothea Mackellar’s “My Country” poses the same question, in Australia.

- Naturally, Kennedy also gives us Glover’s best known: “Magpies”, which every schoolchild can recite in New Zealand. But more than half of Kennedy’s selections are new to me, even if the names of the poets are often familiar. There is a surprise at every turned page.

- Anna Jackson’s “The Treehouse” is a smoothly-crafted, 14-line song of passion, originally from her 2003 collection Cattullus for Children.

- The name of Jackson’s 2003 collection gave the clue, since this poem is finely-crafted to be read to children, but to have a wholly different significance for adults:

… as if we lie awake

In a treehouse, shining a torchinto the forest around us,

losing the beamin the dark.

- There are poems in te reo Māori, usually also rendered in English. Individual te reo words have bled into standard New Zealand English seamlessly, but translation remains necessary.

- But the master Māori poet, Hone Tuwhare’s “Nocturne” was composed in English, his second language. That English version is given, with a translation into te reo by Selwyn Muru.

- One way of reading this anthology is as a way of re-imagining how such a book might now be compiled in Australia. Are we at the point where Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker) might be translated into Moondjan? The parallels of a “settler” society, and the consequences of “settlement”, cannot be ignored, though.

- The quality of the poetry, selected for its memorability, shines through.

- It is always possible to argue with what is not included in an anthology. I have pasted Elizabeth Morton’s “Storyteller” and Charles Brasch’s “Winter Anemones” in the back of this collection. That is everyone’s solution, instead of arguing the toss on selection.

- This is a good, informative and modern collection of New Zealand verse, taking in favourites, and introducing newer poets.

- The editor, Anne Kennedy, is a noted poet and novelist. Her first novel, The Last Days of the National Costume, a story set in the dog-days of the Mercury Power electricity outage in Auckland in 1998, was good enough to cause a difference between friends (one hates it, one loves it). Her latest collection of poems is The Sea Walks into a Wall, 2021.

*David is an Australian who keeps a close eye on our cousins across The Ditch.

Paper written by David Marks KC, and co-presented with Rebecca Rose of Bankside Chambers, Auckland, at the 2023 BAQ Annual Conference held at the W Brisbane Hotel on 3-4 March 2023.

Technique in Trust Litigation – A Worked Scenario

Most chambers in Brisbane are 10 minute’s walk to the State Library of Queensland (SLQ).

Up North, you can use the electronic services, and order physical books delivered via your municipal library.

If you are a professional or student in Queensland, you should register, get your card number, and start using it. (See end for links.)

And join the National Library of Australia (NLA). The electronic services are different. The services are different. For example, NLA will scan you a chapter cheaply. You need both memberships.

I’m also an interstate member of SA and Victorian State libraries. (See “Bolt-hole”, below.)

Why join?

Borrow stuff the Council library does not hold

I’m currently reading a book that our (large & excellent) municipal library does not own. I’ve borrowed from the SLQ.

Yes, you can borrow from SLQ.

Not everything. And note that some State libraries, eg SLSA, don’t lend. So ask.

But I’m on a Hugh Trevor-Roper binge at the moment.

Most of this historian’s more academic stuff is for loan at SLQ. Most is of no interest to the municipal library (with its different mandate).

Really surprising databases

During a recent trial, I needed a scientific journal paper about avian health.

It was available through an NLA subscription service, free.

Note it wasn’t a subscription service SLQ offered.

SLQ was actually my first port of call, as it has excellent access to these academic databases.

NLA was the only ready source for that journal.

You need membership of both SLQ & NLA to provide this kind of cover.

Strong service

Years ago, an expert witness disappeared. We had heard he had died, but it had evidently taken a toll on the next of kin who weren’t responding. I needed to check for a death/funeral notice in the (late, lamented) Bundaberg News-Mail.

I rang SLQ. The September bundle of papers was retrieved from archive to SLQ within the hour.

We ran our application to rely on a new expert witness based principally on that funeral notice.

More recently, when the Pandemic was but new, I got instructions from out-of-state to advise about privileges & immunities of an obscure international entity.

This is important but finicky stuff. That’s why I fight to keep this stuff at the Queensland Bar.

But how to service such instructions, during a Pandemic?

The Supreme Court of Queensland Library (SCLQLD) and the NLA remained open to remote requests for most of the Pandemic. Their service was truly exceptional. These 2 great institutions just powered on, in ways that made colleagues in New Zealand and England marvel.

Most of the material I needed was available via SCLQLD requests.

But this was a truly obscure corner of public international law, given the kind of entity involved.

I wanted background to the history & treaties. A lot of public international law is grounded in custom, sometimes centuries old. You need to know your history.

I asked NLA for a chapter of a book they held.

The scanned chapter turned up the next day, for $18.

(Service standard at NLA is longer. But they had no walk-ins, since the front door was locked at that point of the Pandemic!)

Accuracy and authority of sources

One example.

Why rely on web searches for basic general knowledge?

Barristers practise across a lot of industries and topics.

For important, basic knowledge about an industry or theme – I have my SLQ access to Britannica bookmarked.

Bolt-hole

I am interstate enough for this topic to matter.

Between meetings, the State libraries are quiet bolt-holes, for silent work with good wifi.

A library membership greases the wheel.

I’m a member of SLV and SLSA. (In Sydney, I use my NSWBA interstate membership, and retreat to the excellent NSWBA library in the sub-basement in Phillip Street. But come fully charged, and do ask for help with the wifi.)

Which to join? How?

Obviously, join SLQ and NLA. If you live interstate, join your State’s library.

But first, dust off your municipal library card, or join now. The municipal libraries are fundamental, since they are your gateway, up North, to getting a physical loan from SLQ. The collections are good, just different, and you can indulge your recreational reading pleasurably.

Now, the point of my pitch —

SLQ and NLA application pages are linked. I’ve made the case.

What if you are reading this interstate? State library digital rights seem to be linked to State of residence. If you’re reading this interstate, join your own State library for digital rights.

As Molly Meldrum would say – “Do yourself a favour.” Join your State and National libraries today.