Stuart Bywater Design is widely recognised throughout Queensland and Australia as one of the leading furniture designers and makers in the country.

www.bywaterdesign.com.au

I will commence this review by saying that over the past 40 plus years of practice, I have been involved in a great number of jury trials, both in the criminal and civil jurisdictions, albeit not in Queensland. When I saw this book advertised, my interest was immediately sparked and you will see why, as this review proceeds.

The 12 good people and true are a time honoured method of determining guilt or otherwise in criminal trials and, in the many in which I have been involved, only twice did I think they got it wrong. In one of those cases, I later changed my mind when my client committed another crime using the identical procedure. In the other, to this day, I continue to think their decision was wrong.

Thus, I remain an advocate of jury trial. But my mind could not help but think about whether our approach to these trials was keeping abreast with the times and with the increased use of computer animation, power point presentations and the like. We remain very conservative in our approach to how we present our evidence to a jury. In contrast, we would not think of giving a lecture to the public without modern aids.

This excellent book is written by Dr. Horan, an academic Victorian barrister who has taken my thoughts to a much more refined level, resulting in a text from which anyone who engages in jury trials, or intends to do so, can gain a great deal.

The book considers juries from the beginning, that is, jury selection, right through to the presentation of evidence to them. Juries in the 21st Century considers the results of jury polling in a number of States as well as the results of some mock jury trials. The book, generally, tries to use this feedback to guide the legal profession in attaining a better understanding of how jurors are selected and what makes a jury tick.

Perhaps to me, the most informative chapter of this book is that which considers scientific evidence. I include in that subject, statistical evidence. Very few of us would ever forget the Lindy Chamberlain cases and how forensic evidence seemed so important to that jury’s decision. Since then, we have had a proliferation of cases apparently decided almost solely on DNA evidence. But as Dr. Horan points out, the legal profession accepts, without reservation and perhaps too readily, statistical evidence which is probably not within the expertise of the witness and which, in any event, may be suspect. She considers, albeit briefly, mock jury research with 571 Australian high school students in which they were willing to convict even when presented with evidence having low statistical significance. The mock jurors recorded the same conviction rate for random match probabilities of 4000 and 400,000 and were more likely to convict when the figure went up to 4 million.

I have sometimes seen what Dr. Horan and others have called the “CSI effect” where juries are so attuned to crimes being solved within an hour, purely by scientific evidence, that they expect the prosecution to present them with the case, all gift wrapped, in the same way. We know that, in real life, this rarely happens. I refuse to watch such television shows, I hasten to add, because it is so easy to pick holes in them.

Dr. Horan also considers expert evidence in the sense of joint experts, single experts, concurrent expert evidence and, importantly, the problems that arise where the prosecution experts and defence experts give their evidence days or weeks apart, making it particularly difficult for the jury to compare them.

Finally, I commend to you the discussion of what evidence should be made available to the jury when it considers its verdict and in what form. We all know how juries are directed that they must not make their own inquiries but must base their decision on the evidence heard in the Court. In a matter I was involved in some years ago, notwithstanding this direction, the foreman went out at lunch time and obtained documents from a local council which he then shared with the other jurors. That jury was discharged and a retrial ordered. Dr. Horan discusses detective juries in some thought provoking depth.

Let me leave you with the suggestion that every page of this book contains thoughtful material of how we can better present our evidence to a jury. I did not agree with everything that was said. But every comment that I read was thought provoking and challenged my own personal views. Surely, that is the hallmark of a first rate textbook.

This newly published book is highly recommended.

Brian Morgan

Chambers

27 February 2013

Ethics: “How to Handle Complaints”

Date: Thursday 21 March 2013

Time: 5.00pm — 6.00pmVenue: Banco Court, Supreme Court Complex, George Street

Presenters: Peter Davis S.C., John Briton Legal Services Commissioner and panel

Accreditation details: BAQ1304, 1 CPD point, ethics strand

The nab North Queensland Law Association Conference 2013

-

- DIVERSITY & EQUALITY IN THE WORK PLACE – Kevin Cocks, Commissioner of the Anti-Discrimination Commission Queensland

- THE 2013 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY MAYO LECTURE – The Honourable Justice Susan Kiefel AO, High Court of Australia

- THE MALAYSIAN RIGHTS PROJECT: KEY TRENDS AND WINS POST 2008 – Edmund Bon, Partner, Chooi & Company, Malaysia

Commercial Stream:

- UNINTENDED ADEMPTION BY AN ATTORNEY AND THE END OF THE RE VIERTEL EXCEPTION -Tony Collins, Barrister

- PPSA — A YEAR ON AND COUNTING: WHAT WE HAVE LEARNT – Scott Butler – Partner, McCullough Robertson

- ACCESSORIAL LIABILITY OF LAWYERS UNDER THE CORPORATIONS LEGISLATION – Dr Tom Middleton – Lecturer, James Cook University

- THE TOP 10 ISSUES IN AGRIBUSINESS TRANSACTIONS IN THE CURRENT ENVIRONMENT Mark Woolley – Principal, McInnes Wilson Lawyers

- A PANEL DISCUSSION ON ANDREWS v ANZ AND OTHER RECENT CASES -Â The Honourable Justice David North SC, Supreme Court of Queensland; Dean Morzone SC, Barrister;Â Tony Moon, Â Barrister

- PLAIN ENGLISH DRAFTING – Don Fraser QC, Barrister

Family Law Stream:

- SIGNIFICANT & SUBSTANTIAL CHANGE — RICE V ASPLUND – Janice Mayes , Barrister

- ADVOCACY IN THE FAMILY COURT The Honourable Justice Peter Tree Family Court of Australia

- PLUS CA CHANGE… THE DOMESTIC AND FAMILYÂ VIOLENCE PROTECTION ACT 2012 Stephen Page, Partner, Harrington Family Lawyers

- A TALE OF SEVERAL CITIES — DIFFERENCES IN APPROACH TO RELOCATION CASES – Michael Fellows, Barrister

- PROPERTY CASE LAW UPDATE – Justine Woods – Partner, Cooper Grace Ward Lawyers

- POST MORTEM ON THE ITALIAN CASE — THE JUDGE’S PERSPECTIVE – The Honourable Justice Colin Forrest, Family Court of Australia

Litigation stream:

- CCTV FOOTAGE AND EXPERT EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL TRIALS — WHAT ARE THE LIMITS? – Justin Greggery, Barrister

- NDIS, NIIS: HOW THEY COULD AFFECT COMMON LAW RIGHTS – Rod Hodgson, Principal, Maurice Blackburn

- IS AN ADVICE ON EVIDENCE NECESSARY? Tim Matthews, Barrister

- PREPARATION AND PRESENTATION OF A SUCCESSFUL APPLICATIONS TO THE COURT – The Honourable Justice James Henry, Supreme Court of Queensland

- PERSPECTIVES FROM THE P & E COURT – The Honourable Justice Michael Rackemann & The Honourable Justice Stuart Durward, District Court of Queensland; John Taylor, Registrar of the Planning & Environment Court

- VOIDABLE TRANSATIONS (BANKRUPTCY) – Tina Hoyer, Solicitor, Australian Tax Office; Michael Brennan – Principal, Offermans Partners

Barrister’s Compulsory CPD

- ETHICS FOR THE BAR – Roger Traves SC – President, Bar Association of Queensland; Peter Davis SC – Vice President, Bar Association of Queensland

- ADVOCACY FOR THE BAR – Roger Traves SC – President, Bar Association of Queensland; Peter Davis SC – Vice President, Bar Association of Queensland

- BUILDING RESILIENCE FOR LAWYERS – Dr. Qusai Hussain – Director, Psylegal

Voiceless Animal Law Lecture Series 2013

1 CPD point per hour of attendance.

Strand: Non-allocated

Accreditation codes:

9 May at Griffith University, Brisbane: VALLS130509

10 May at Clayton Utz, Brisbane:VALLS130510

13 May at Bond University, Robina:VALLS130513

When the New Press published The New Jim Crow in hard back in 2010, the print run was a commendable 3,000 copies for a scholarly work. When the paperback edition was published in January, 2012, the book sold 175,000 copies in less than two months. Even as The New Jim Crow has been a publishing phenomenon of extraordinary proportions, it has been an even greater phenomenon in the world of ideas.

The thesis of The New Jim Crow is simple. As the author, Michelle Alexander acknowledges, in the introductory pages, the book’s seminal arguments have been put forward for some time but have not reached the wide circle of listeners that is necessary for change to be possible.

Alexander argues that the impact on Afro-Americans of incarceration and the other control systems of the criminal justice system have created a new caste system similar to that maintained by the Jim Crow laws that took hold in the United States after the Reconstruction efforts faltered and remained effective until dismantled by the Civil Rights legislation in the early 1960s. The United States legal system is designed to maintain the vast majority of Afro-Americans as part of a caste that has reduced opportunities for success and a vastly increased probability of reduced rights; reduced living standards; and the high probability of spending much of their lives being shuffled between prison and parole.

The pervasiveness of the caste system has been greatly enhanced by the War on Drugs, a legislative and administrative complex of activities that commenced in the early 1980s and was persuasively articulated, for the first time, by President Reagan. The War on Drugs has been overwhelmingly applied against Afro-American and, to a lesser extent, Latino communities. Alexander quotes persuasive data from surveys and hospital emergency centres that indicate that white Americans indulge in illicit drugs to the same extent (or more) as Afro-Americans. But it is Afro-American communities who bear the brunt of law enforcement and a slanted legal system under the state of war.

The War on Drugs has been heavily resourced by all administrations since 1982. Local and state police forces have been lured into the practices of the war by the promise of generous resourcing. The tactics promoted have included random stops of vehicles and random searches of pedestrians. Police forces have been heavily armed and riot police and their associated methods have been used to carry out these tactics and to execute drug search warrants. All of this behaviour would have been politically suicidal if used against most white communities. However, because the methods have been applied on racial lines, the political outfall has not been negative and the powerlessness of ghetto neighbourhoods has been reinforced as has the racial stereotype of the drug criminal.

The effect on individuals caught up in the drug war has been exacerbated by laws passed making serious crimes of possession of small amounts of relatively harmless drugs. The widespread use of mandatory sentencing has meant that young black men have spent years in jail while white college boys, factory workers and financial industry heavies continued to enjoy their recreational use of various illegal drugs. The laws concerning the use of crack cocaine (principally, a drug of choice among Afro-American users) have been much more punitive than the laws governing sentencing for powder cocaine, a drug more popular with white users.

The creation of a permanent caste was reinforced by punitive laws passed against anybody convicted of a felony. These continue to affect the lives of Afro-American men after they are released from prison. Convicted prisoners lose their rights to public housing; to various kinds of welfare including food stamps; and often to the chance to obtain employment through restrictions on obtaining licences for a plethora of occupations. Difficulties in obtaining private transport and the vagaries of public transport mean that the few far away jobs are difficult to gain or maintain. And complying with conditions of parole is equally fraught. The net result is a by no means merry go round by which released prisoners find their way back to prison. Even participation in the political life of society is denied as most states have laws preventing ex-prisoners and those convicted of felonies from voting.

The law fails the members of the new caste on many levels. Public defence lawyers are under resourced and few in number. The odd wealthy white person who stumbles into the cross-fire of the War on Drugs is able to hire a lawyer and, with the threat of a well-resourced defence case, earn a favourable deal at the plea bargaining table. Meanwhile those arrested in the racially directed sweeps through the ghetto are lucky to see a lawyer for more than a few minutes and are forced to plead guilty to one set of charges, even when the evidence is weak or they are innocent, under threat of charges that produce even higher sentences. Plea bargaining is a great system for those who come to the table with power. The system ensures that Afro-Americans constitute those without.

A wave of decisions of the Supreme Court have validated and legitimised the racist biases of the system. In McCleskey v Kemp, a death penalty case, the Court received overwhelming evidence that the death penalty in the State of Georgia was applied on racial lines both in respect of the colour of the defendant and the colour of the victim.2 However, in a decision that has been called the Supreme Court’s worst decision, it was ruled that such statistical evidence was not only unpersuasive but inadmissible. Only evidence of overt racial bias in the particular case would be admissible to set aside a decision. Such evidence is very hard to come by in a system that protects the secrecy of the reasoning process of jurors.

In United States v Clary, Judge Clyde Cahill of the Federal District Court of Missouri, challenged the 10-1 discrepancy in the sentencing laws between crack and powder cocaine and carefully analysed the lynch mob mentality by which such discrepancies had been written into the statute books. He refused to sentence an eighteen year old first offender to 10 years in federal prison and, instead, sentenced him to four years, as if the substance was powder cocaine. The Appeals Court overturned the decision and Mr. Clary, who had served his four years, was ordered back to prison to serve the remaining six.

Another key part of the racist structure was preserved in Armstrong v United States. This time, the Supreme Court overruled decisions in the courts below them that would have allowed defnce counsel to have access to the files of prosecutors in other cases. The defence was seeking to argue that the clients were being hit with federal charges (and more severe penalties) in circumstances where prosecutors would not have done the same thing to white defendants. The Supreme Court ruled that the defendants had to have specific evidence of a white defendant who had been treated differently before discovery would be ordered. This was, of course, a classic Catch 22 in that the only way in which clear evidence of such racially biased exercise of prosecutorial decisions could be found was in the files of previous decisions.

Purkett v Elm put beyond reach the racist use of peremptory challenges in jury selection to obtain all-white juries even to the point of saying that prosecutors could get away with nonsensical and contradictory reasoning providing they did not actually come out and admit a racist reason.

A series of decisions have blessed the racially biased approach to law enforcement by police officers and the forces for whom they work. The most effective dismantling of the Constitutional and legislative protections that might have been available occurred in Alexander v Sandoval. Sandoval was about driver’s licence tests being administered only in English. However, it dismantled the effect of key parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 holding that regulations made under Title VI of that Act gave no private right of action. As a result, those who suffered racist discrimination, including in law enforcement, could not make any effective claims against that discrimination.

The dismantling of protections against racially slanted law enforcement has been accompanied by another line of cases that has dismantled Fourth Amendment protections against searches without cause carried out as part of the War on Drugs. Florida v Bostick, Schnecklothe v Bustamonte, Ohio v Robinette, Atwater v City of Lago Vista and Whren v United States form part of this series of cases. The lack of limits on police stopping and searching forms a powerful tool in the racially biased enforcement of drug laws.

The New Jim Crow is not an arid academic study. Alexander tells the stories of the individuals caught up in the War on Drugs, including many of the defendants who have lent their names to the cases that now stand as lighthouses marking the rocks of racial injustice. These personal stories are harrowing as the statistics are shocking.

In the period of less than three decades since the War on Drugs was launched,3 the population incarcerated in United States jails have grown 800 per cent from around 300,000 to over 2 million. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, beating countries like Russia, China and Iran. In Germany, 93 people per 100,000 are in jail. In the United States, it is 750 per 100,000.

The United States has a higher proportion of its black population incarcerated than did South Africa at the height of apartheid. In Washington DC, it is estimated that 3 out of 4 young black men (and nearly all of those in the poorer neighbourhoods) can expect to serve time in prison. And Washington DC is no different to black communities located across America.

These figures arise despite the studies which reveal that whites, particularly white youth, are more likely to engage in drug crime than people of colour. And despite the fact that drug use was on the decline when the great War on Drugs was released.

I was particularly fascinated by the final chapter of The New Jim Crow. Alexander discusses the strategies to wind back the creation and maintenance of caste using the justice system and the structural and conceptual barriers that lie in the way.

The structural issues include the financial dependence of often remote rural communities on their new found prison industries including the jobs that prisons create. They include the financial and social addiction of state and local government to police funding that includes the bankrolling of the latest weapons as well as the employment of many staff.

The conceptual problems include the commitment of civil rights and Afro-American rights and legal advocacy groups to the dream of a colour blind discourse and the defence of affirmative action within the educational and employment spheres. Alexander identifies her own educational experience as benefiting from affirmative action.

The New Jim Crow describes a racial bribe offered to privileged Afro-Americans to gain respectability, opportunity and success while their fellow citizens are stuck in the new caste enforced by a racist law enforcement and legal systems. It also describes the way in which disadvantaged whites have always been seduced by caste systems aimed at racial minorities including the system she describes. Disadvantaged whites, while they suffer at the hands of the economic system which keeps them poor and others rich, can always rejoice that they are not black and do not have assault vehicles proceeding through their neighbourhoods administering body, vehicle and dwelling searches and carrying their young men back and forth to prison.

Alexander examines these concerns and more and, tentatively, charts a way forward to fight for real change to dismantle the new caste system.

The New Jim Crow will not stand on book shelves slowly gathering dust. At time of writing, a Google news search for the book’s title found discussion groups at Plymouth; at Princeton; and at Pasadena among others examining and sharing the ideas articulated in The New Jim Crow.

The caste system described by Michelle Alexander exists because most people do not believe it exists. Hopefully, The New Jim Crow, in describing the system, has started the movement for change that will dismantle it for ever. And, hopefully, sooner than later.

Stephen Keim

Clayfield

24 February 2013

Footnotes

1. The New Press is an independent publisher founded in 1992. It is dedicated to widening the audience for serious intellectual discussion and seeks to publish titles which promote serious debate. It also seeks to deal with subjects and audiences which are underrepresented in the work of commercial publishers.

2. A black defendant accused of killing a white victim was most disadvantaged.

3. The statistics in The New Jim Crow tend to come from just past the middle of the last decade. This is a factor of time of publication and writing of the book and the time it takes for reliable statistical studies to be published.

It was Sir Robert Megarry FBA PC who, with his life-long interest in the detail of the law, authored Miscellany-at-law (1955), Arabinesque-at-law (1969), Inns Ancient and Modern (1972), A Second Miscellany-at-Law (1973) and A New Miscellany-At-Law (2005).

At Cambridge, Sir Robert was the recipient of a third class degree in that his focus had been on music, football, tennis and even the obtaining of a pilot’s licence. His ‘miscellany’ books are, perhaps, indicative of the personality of Sir Robert. The 2005 book was his last before his death in October 2006.

The Honourable Keith Mason AC refers to Sir Robert’s series in his preface to Lawyers Then and Now and modestly states that Megarry set standards of scholarship and literary verve that could not be emulated. Mason also refers to many years of conversations with Leslie Katz; Katz, himself, being known for his interesting legal articles on matters as diverse as Conan Doyle and Dickens.

In this 2012 publication, Mason, for example, states: “For judges, long years of sitting literally on a pedestal where counsel invariably laugh outwardly at one’s jokes are poor training grounds for humility and frank self-assessment”.

Lawyers Then and Now is an interesting and entertaining book. It is a combination of light-hearted legal history and the author’s broad experiences of a life ‘in the law’. Graduating from the University of Sydney in 1970, Mason was admitted as a solicitor before commencing at the Bar in 1972. He was appointed as a QC in 1981 and held office as the Solicitor-General of New South Wales from 1987 to 1997. Mason concluded his time as President of the Court of Appeal in 2008 and is currently a visiting professorial fellow at the University of New South Wales. The book also ‘reflects’ the broad and significant group of legal-related persons who provided stories and assistance to His Honour, as referred to in the preface.

The author’s interest in legal history is displayed throughout, with appropriate context provided for each entertaining anecdote. The contents of the work are divided into four general parts: “beginnings”, “people of the law”, “law and the wider world” and “epilogue”.

In addition to the frequent humorous legal ‘exchanges’, the author has managed to incorporate a significant amount of historical background into the text, appropriately expanding upon what might otherwise be bare stories. Using this methodology, the book has a fluent ‘manner’ in articulating what might otherwise be dry historical occurrences within the law.

His Honour expounds confidently in the book upon many matters that could be said to be controversial. For example, at page 142, Mason refers to “a growing list of … QC imposters” being former superior court judges now retired who continue to use the post-nominal.

As the book is read, the reader gains a consciousness of the depth of knowledge contained from which the book has been drawn. This work is an interesting balance to other rigorous publications by Mason, such as Mason & Carter’s Restitution Law in Australia.

This text has more substance and detail than the title suggests. It is well referenced and answers questions about matters which are of importance in terms of understanding the Australian legal system today.

Lawyers Then and Now is an easy read for anyone with an interest in the law.

Dominic Katter

Chambers

15 March 2013

CIVIL APPEALS

CIVIL APPEALS

HM Hire Pty Ltd v National Plant and Equipment Pty Ltd & Anor [2013] QCA 006 Margaret McMurdo P, Fraser and Gotterson JJA 5/02/2013

General Civil Appeal — where an adjudicator determined the appellant should make a progress payment to the respondent — where the first respondent hired mining equipment to the appellant — where payment claim made under the Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 (Qld) (“the Act”) — where subcontract required appellant to perform clear and grub works, topsoil stripping and placement at site — where work performed was excavation and removal of timber and topsoil from site — whether work carried out under subcontract was “construction work” — whether work carried out fell within the exclusion under s 10(3)(b) of the Act — whether adjudication determination was outside jurisdiction — whether rental agreement between appellant and first respondent was a “construction contract” — whether rental agreement is contract where equipment was supplied for use “in connection with” carrying out construction work — where the hired equipment was to be used by the hirer in carrying out work a substantial quantity of which was “construction work” and some of which was not — where the equipment supplied by NPE to HM Hire was suitable for use by HM Hire in constructing roads and drains — where even though the construction work was not expressly identified by the parties as an intended use of NPE’s equipment and even though it remained open to HM Hire to decide which equipment in its fleet would be used in which work, the rental agreement should be regarded as a contract under which NPE undertook to supply equipment to HM Hire for use “in connection with” the carrying out of construction work. Appeal dismissed with costs.

Borhani v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board [2013] QCA 014 Chief Justice and Fraser JA and Dalton J 12/02/2013

Application for Admission — where the applicant began his legal studies at the James Cook University in 1999 — where between 2001 and 2004 Mr Borhani was enrolled as a student of QUT studying towards the dual degrees of Bachelor of Business and Bachelor of Laws — where Mr Borhani enrolled in 34 subjects of which he failed nine with a grade point average of 3.563 — where between 2004 and 2009 Mr Borhani undertook no legal studies — where QUT introduced a new Bachelor of Laws in 2009 — where Mr Borhani resumed his studies in 2009 and was granted advanced standing for previous legal studies by the Queensland University of Technology — where the applicant completed four subjects for which he was awarded grades of 5, 7, 6 and 6 — where QUT accorded him with a grade point average of 6 — where Mr Borhani’s enrolment was cancelled due to him not having paid a required fee — where upon paying fee and re-enrolling, Mr Borhani found that his GPA was listed as 4.73 — where in the middle of March 2010 Mr Borhani complained to the ombudsman at QUT as part of a formal student grievance procedure to achieve his aim of reinstating his academic record as it appeared prior to January 2010 — where pursuit of this grievance procedure was, surprisingly and disconcertingly given the true facts of the matter, successful, and his academic record was returned to its pre-January 2010 state so that it showed “Course GPA: 6.000” — where it is undoubtedly the case that QUT did issue a degree with First Class Honours to Mr Borhani — where the evidence was that with a grade point average of 4.73 Mr Borhani was not entitled to a degree with honours of any kind from the QUT, much less a degree with First Class Honours — where it was remarkable that QUT was prepared to issue the academic transcript in the form which was exhibited to Mr Borhani’s affidavit of 2 December 2011, and to award Mr Borhani a law degree with First Class Honours — where it cannot be imagined that a student in Mr Borhani’s position could reasonably have understood that he or she was entitled to a degree with First Class Honours, or had a grade point average of 6 over the entirety of their law degree — where Mr Borhani correctly recognises in his affidavit that his reliance upon the degree showing an award of First Class Honours, and a transcript showing a course GPA of 6, without explanation, was misleading — where it is apparent from the correspondence that Mr Borhani was aware of the significance of his grade point average to his employment prospects, and aware that untruthfulness in relation to his academic results would be regarded in the legal profession as a very serious matter — where it is relevant in assessing whether Mr Borhani is a fit or proper person for admission that he was nearly 30 when he made his application for admission and was therefore some years older than the average applicant — where it is also relevant that between 2004 and 2010 he worked as a land developer and as a consultant to land developers so that he had more commercial and business experience in the real world than the average university graduate at the time of the events in question. Application refused.

Application for Admission — where the applicant began his legal studies at the James Cook University in 1999 — where between 2001 and 2004 Mr Borhani was enrolled as a student of QUT studying towards the dual degrees of Bachelor of Business and Bachelor of Laws — where Mr Borhani enrolled in 34 subjects of which he failed nine with a grade point average of 3.563 — where between 2004 and 2009 Mr Borhani undertook no legal studies — where QUT introduced a new Bachelor of Laws in 2009 — where Mr Borhani resumed his studies in 2009 and was granted advanced standing for previous legal studies by the Queensland University of Technology — where the applicant completed four subjects for which he was awarded grades of 5, 7, 6 and 6 — where QUT accorded him with a grade point average of 6 — where Mr Borhani’s enrolment was cancelled due to him not having paid a required fee — where upon paying fee and re-enrolling, Mr Borhani found that his GPA was listed as 4.73 — where in the middle of March 2010 Mr Borhani complained to the ombudsman at QUT as part of a formal student grievance procedure to achieve his aim of reinstating his academic record as it appeared prior to January 2010 — where pursuit of this grievance procedure was, surprisingly and disconcertingly given the true facts of the matter, successful, and his academic record was returned to its pre-January 2010 state so that it showed “Course GPA: 6.000” — where it is undoubtedly the case that QUT did issue a degree with First Class Honours to Mr Borhani — where the evidence was that with a grade point average of 4.73 Mr Borhani was not entitled to a degree with honours of any kind from the QUT, much less a degree with First Class Honours — where it was remarkable that QUT was prepared to issue the academic transcript in the form which was exhibited to Mr Borhani’s affidavit of 2 December 2011, and to award Mr Borhani a law degree with First Class Honours — where it cannot be imagined that a student in Mr Borhani’s position could reasonably have understood that he or she was entitled to a degree with First Class Honours, or had a grade point average of 6 over the entirety of their law degree — where Mr Borhani correctly recognises in his affidavit that his reliance upon the degree showing an award of First Class Honours, and a transcript showing a course GPA of 6, without explanation, was misleading — where it is apparent from the correspondence that Mr Borhani was aware of the significance of his grade point average to his employment prospects, and aware that untruthfulness in relation to his academic results would be regarded in the legal profession as a very serious matter — where it is relevant in assessing whether Mr Borhani is a fit or proper person for admission that he was nearly 30 when he made his application for admission and was therefore some years older than the average applicant — where it is also relevant that between 2004 and 2010 he worked as a land developer and as a consultant to land developers so that he had more commercial and business experience in the real world than the average university graduate at the time of the events in question. Application refused.

Attorney-General for the State of Queensland v Fardon [2013] QCA 016 Muir JA 14/02/2013 (delivered ex tempore)

Application for Stay of Execution — where the respondent had a history of sexual offending — where the respondent was detained in custody for an indefinite term for care, control or treatment — where the respondent sought a periodic review of the continuing detention order — where the primary judge ordered that the continuing detention order be rescinded and that the respondent be released from prison by 4.00 pm on 14 February 2013 — where the applicant seeks a stay pending appeal of the orders of the primary judge — where the respondent placed reliance on a number of press reports, or comments, made by the Corrective Services Commissioner, and the Police and Community Safety Minister — where relevant considerations on stay applications include: the principle that judgments are not to be regarded as merely provisional; whether the applicant may suffer irretrievable harm if successful on the appeal; and whether the applicant has an arguable case — where the applicant has the onus of proof — where the ordering of the stay will deprive the respondent of the personal liberty to which the order under consideration would entitle him at 4 pm today — where a countervailing consideration is the risk to the community arising from the possibility of the respondent committing a sexual offence, if released — where having regard to the fact that this Court is able to hear the appeal on 27 February, and that the parties are able to proceed on that day, it is concluded that the balance of convenience favours the grant of a stay — where it would not be in the respondent’s best interests that he be released into the community and at the same time exposed to the risk of being returned to prison within a very short period should the appeal succeed — whether a stay should be granted. Orders of 13 February 2013 be stayed, pending determination of the appeal, respondent be detained in custody until 4 pm on 27 February 2013 pursuant to the Dangerous Prisoners (Sexual Offenders) Act 2003 (Qld).

Weis Restaurant Toowoomba v Gillogly [2013] QCA 021 Margaret McMurdo P and Fraser JA and Daubney J 15/02/2013

Application for Leave s 118 DCA (Civil) — where the respondent suffered personal injury at Weis Restaurant after his chair collapsed under him, thus leading him to fall to the floor — where limitation period for personal injuries action extended pursuant to order under s 31 Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) — where the respondent had resolved to pursue his claim against Weis Restaurant for personal injuries — where appellant contended that identity of defendant was not material fact of decisive character — where the proceeding the respondent had decided to pursue could have simply been instituted against the ‘Weis Restaurant’ business name, regardless of whether it was a registered business or unregistered business name — where importantly, for present purposes, the respondent expressly agreed in evidence that by the middle of 2009, when he first consulted with Mr Booby, his then solicitor, the respondent “had decided to pursue a claim against Weis’s Restaurant” for his injury — where a discretion to extend the limitation period for a personal injuries action when, relevantly, it appears to the Court, inter alia, “that a material fact of a decisive character relating to the right of action was not within the means of knowledge of the applicant” until the date specified in s 31(2)(a) — where the central finding below that the actual identity of the company operating the restaurant was a material fact of a decisive character because it was “critically important to know against whom an action might succeed” cannot be sustained — where on his own evidence, the respondent had, by mid-2009, resolved to pursue his claim against Weis Restaurant for the personal injuries he had suffered as a consequence of the incident on 14 January 2009 — where it is clear that the respondent not only knew of all of the facts which showed (from his perspective) that he had an action with reasonable prospects of success, he had in fact decided to pursue that action — where it was not necessary for him to know the precise legal identity of the owner of the restaurant in order to pursue the action — where on his own evidence, he knew its business name, i.e. “Weis Restaurant” — where the proceeding he had decided to pursue could have simply been instituted against that business name, regardless of whether it was a registered or unregistered business name. Application for leave granted. Appeal allowed, order below set aside, and in lieu thereof, the originating application be dismissed, costs.

Application for Leave s 118 DCA (Civil) — where the respondent suffered personal injury at Weis Restaurant after his chair collapsed under him, thus leading him to fall to the floor — where limitation period for personal injuries action extended pursuant to order under s 31 Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) — where the respondent had resolved to pursue his claim against Weis Restaurant for personal injuries — where appellant contended that identity of defendant was not material fact of decisive character — where the proceeding the respondent had decided to pursue could have simply been instituted against the ‘Weis Restaurant’ business name, regardless of whether it was a registered business or unregistered business name — where importantly, for present purposes, the respondent expressly agreed in evidence that by the middle of 2009, when he first consulted with Mr Booby, his then solicitor, the respondent “had decided to pursue a claim against Weis’s Restaurant” for his injury — where a discretion to extend the limitation period for a personal injuries action when, relevantly, it appears to the Court, inter alia, “that a material fact of a decisive character relating to the right of action was not within the means of knowledge of the applicant” until the date specified in s 31(2)(a) — where the central finding below that the actual identity of the company operating the restaurant was a material fact of a decisive character because it was “critically important to know against whom an action might succeed” cannot be sustained — where on his own evidence, the respondent had, by mid-2009, resolved to pursue his claim against Weis Restaurant for the personal injuries he had suffered as a consequence of the incident on 14 January 2009 — where it is clear that the respondent not only knew of all of the facts which showed (from his perspective) that he had an action with reasonable prospects of success, he had in fact decided to pursue that action — where it was not necessary for him to know the precise legal identity of the owner of the restaurant in order to pursue the action — where on his own evidence, he knew its business name, i.e. “Weis Restaurant” — where the proceeding he had decided to pursue could have simply been instituted against that business name, regardless of whether it was a registered or unregistered business name. Application for leave granted. Appeal allowed, order below set aside, and in lieu thereof, the originating application be dismissed, costs.

MSI (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Mainstreet International Group Ltd [2013] QCA 027 White and Gotterson JJA and Applegarth J 26/02/2013

General Civil Appeal — where the appellant sought to recover as a debt an overdue loan repayment, interest thereon and costs — where the appellant commenced proceedings without leave of the Supreme Court — where a submission was made by counsel on behalf of Mainstreet that the proceeding itself was invalid because, as his Honour summarised, it was a proceeding “purporting to be brought by a receiver without authority from the Supreme Court pursuant to section 471B of the Corporations Act” — where the learned judge accepted the submission and that day made an order striking out the proceeding, with costs reserved — whether leave of the Supreme Court was required in order for the appellant to commence proceedings for the recovery of a debt — where by virtue of s 471C, the prohibition of the commencement or continuation of legal proceedings in the circumstances which it addresses, except with the leave of the Court, does not affect the right to realise or otherwise deal with a security interest of a secured creditor — where plainly the charge created by the Deed in favour of the Chargor was a security interest as defined — where at the time of commencement of the District Court proceeding, Central Coast, as Chargor under the Deed, was a secured creditor of MSI: there was a debt owed by MSI to Central Coast under the Loan Agreement which was secured by the charge — where the commencement and continuation of the District Court proceeding is apt to be characterised as a realisation of Central Coast’s security interest for the purposes of s 471C — where it was submitted that it is only when a debt is uncontested, that it is capable of being realised for the purposes of the section — where no authority was cited for the submission — where this is plainly wrong — where legal proceedings to recover a charged debt which, by the course of pleadings, require the making of a judicial determination of whether or not the debt exists are no less a process of realisation of the security interest than are legal proceedings in which the existence of the debt is not contested — where the Court’s attention was drawn to the newly enacted s 118B of the District Court of Queensland Act which, if applicable to this application, would have required that leave to appeal the costs order be obtained from a District Court judge and not from this Court under s 118(3) — where to determine how this section operates transitionally is regulated by the Civil Proceedings (Transitional) Regulation 2012, s 22 of which provides that s 118B does not apply if, immediately before commencement of it, a person having, under the pre-amended s 118, a right to appeal to this Court has started the appeal but it has not been determined — where its character as a right to appeal was not diminished by reason of its being exercisable only with the leave of this Court — where s 118(3) therefore continues to govern this application. Appeal allowed, orders below set aside, matter remitted to the District Court for further consideration and determination, costs.

CRIMINAL APPEALS

R v Jobsz [2013] QCA 005 Chief Justice, White and Gotterson JJA 5/02/2013

R v Jobsz [2013] QCA 005 Chief Justice, White and Gotterson JJA 5/02/2013

Sentence Application — where the the applicant pleaded guilty to five drug-related offences of varying severity — where the applicant was sentenced to four and a half years imprisonment to be suspended after 16 months with other lesser concurrent sentences — where the judge did not impose a separate sentence in respect of each offence — where the sentence imposed would be excessive for the less serious offences committed — whether the failure to impose separate sentences in respect of each offence requires that the applicant be re-sentenced — whether addiction is a mitigating circumstance for a drug offence in light of positive rehabilitation prospects — where the need for general deterrence in sentencing for this sort of crime must be given appropriate weight: this was, as said, a case of not insubstantial trafficking in two schedule 1 drugs, albeit carried on over a shortish period — where the applicant did not participate in a record of interview, and save for his pleas of guilty, did not subsequently cooperate with the authorities — where notwithstanding the seriousness of the trafficking, bearing in mind the comparatively short timeframe and the applicant’s personal circumstances, it was not a case calling for a salutorily high sentence. Application granted, appeal allowed, sentence set aside and replaced with imprisonment for four years imprisonment to be suspended after 12 months with other lesser concurrent sentences.

R v Dowel; Ex parte Attorney-General (Qld) [2013] QCA 008 Muir and Fraser JJA and Dalton J 8/02/2013

Sentence Appeal by Attorney-General (Qld) — where the respondent pleaded guilty to one count of unlawful trafficking in Schedule 1 drugs — where the respondent was 19 at the time of offending — where the respondent had no prior criminal history — where the respondent made a considered decision to sell Schedule 1 drugs for profit — where the respondent voluntarily ended his involvement with drugs — where the respondent continued in full time employment and studied for his apprenticeship throughout the 21 months he was on bail for the subject offence — where on a Crown appeal, the Court is required to have regard to the circumstances existing at the time of hearing the appeal and there is a reluctance to disturb a situation in which a respondent has availed himself or herself of a non-custodial sentence to gain, or remain in, employment and pursue a life free from crime and criminal influences — where the respondent was sentenced to four years imprisonment, wholly suspended — whether the sentence was manifestly inadequate. Appeal dismissed

Sentence Appeal by Attorney-General (Qld) — where the respondent pleaded guilty to one count of unlawful trafficking in Schedule 1 drugs — where the respondent was 19 at the time of offending — where the respondent had no prior criminal history — where the respondent made a considered decision to sell Schedule 1 drugs for profit — where the respondent voluntarily ended his involvement with drugs — where the respondent continued in full time employment and studied for his apprenticeship throughout the 21 months he was on bail for the subject offence — where on a Crown appeal, the Court is required to have regard to the circumstances existing at the time of hearing the appeal and there is a reluctance to disturb a situation in which a respondent has availed himself or herself of a non-custodial sentence to gain, or remain in, employment and pursue a life free from crime and criminal influences — where the respondent was sentenced to four years imprisonment, wholly suspended — whether the sentence was manifestly inadequate. Appeal dismissed

Constable S J Miers v Blewett [2013] QCA 023 Holmes and Fraser JJA and Atkinson J 22/02/2013

Application for Leave s 118 DCA (Criminal) — where the respondent was convicted in the Magistrates Court of two offences under s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 (Qld) — where the respondent had previously been convicted of two offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 (Qld) — where prosecution sought to tender the whole of the respondent’s criminal history — where prosecution did not seek to rely on the criminal history to  raise the maximum sentence, but to increase the penalty that could be imposed on the respondent — where no notice was served by the prosecution under s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) in relation to the prosecution’s reliance on the respondent’s previous convictions — where Magistrate rejected the tendering of the whole of the respondent’s criminal history — where on appeal in the District Court the judge upheld the Magistrate’s decision — where none of the respondent’s criminal history was taken into account in determining the sentence — whether the lack of notice under s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) had the effect of preventing the court from taking the two previous convictions against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 (Qld) into account — whether evidence of the two previous convictions for offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act should be admissible — whether other prior non-domestic violence offence convictions of the respondent should have been taken into account in determining the sentence — where at the heart of the proposed appeal is a challenge to the construction of s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 in Washband v Queensland Police Service [2009] QDC 243 — where in some cases, taking previous offences into account in obedience to those provisions will result in a more severe penalty than would otherwise be imposed, but a previous conviction which only has that potential effect is not caught by s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 — where s 47(5) treats a previous conviction as an example of a circumstance which, in terms of s 47(4) “…renders the defendant liable…to a greater penalty than that to which the defendant would otherwise have been liable” — where s 47(4), and thus s 47(5), refer to a circumstance which increases what otherwise would be a defendant’s potential liability for punishment for the offence — where s 47(5) refers to a circumstance, two previous convictions for the same offence, which results in a greater maximum penalty — where accordingly s 47(5) did not require notice to be given of any of the respondent’s previous convictions for offences which were not offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 — where those previous convictions should have been taken into account by the Magistrate if and to the extent that they were material to the sentences to be imposed for the current offences — where the decision to the contrary in Washband should be overruled — where on the authority of The Queen v De Simoni (1981) 147 CLR 383, the inadmissibility of the two previous convictions could not be avoided merely by the prosecutor disclaiming reliance at the sentence hearing upon them as a circumstance rendering the respondent liable to the increased penalty of two years imprisonment — where the prosecutor asked the Magistrate to rely upon both convictions — where that was not open to the Magistrate — where the Magistrate was correct in holding that the evidence of the two previous convictions for offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 should not be received but was in error in not taking into account the respondent’s other previous convictions — where the omission to take them into account may have had an effect upon the sentence, however it is not appropriate to reconsider the sentence or to grant leave for that purpose — where the respondent’s sentence was completed years before the application for leave to appeal was heard by this Court — whether the sentence was manifestly inadequate. Leave to appeal granted, appeal dismissed, applicant to pay the respondent’s costs.

raise the maximum sentence, but to increase the penalty that could be imposed on the respondent — where no notice was served by the prosecution under s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) in relation to the prosecution’s reliance on the respondent’s previous convictions — where Magistrate rejected the tendering of the whole of the respondent’s criminal history — where on appeal in the District Court the judge upheld the Magistrate’s decision — where none of the respondent’s criminal history was taken into account in determining the sentence — whether the lack of notice under s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 (Qld) had the effect of preventing the court from taking the two previous convictions against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 (Qld) into account — whether evidence of the two previous convictions for offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act should be admissible — whether other prior non-domestic violence offence convictions of the respondent should have been taken into account in determining the sentence — where at the heart of the proposed appeal is a challenge to the construction of s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 in Washband v Queensland Police Service [2009] QDC 243 — where in some cases, taking previous offences into account in obedience to those provisions will result in a more severe penalty than would otherwise be imposed, but a previous conviction which only has that potential effect is not caught by s 47(5) of the Justices Act 1886 — where s 47(5) treats a previous conviction as an example of a circumstance which, in terms of s 47(4) “…renders the defendant liable…to a greater penalty than that to which the defendant would otherwise have been liable” — where s 47(4), and thus s 47(5), refer to a circumstance which increases what otherwise would be a defendant’s potential liability for punishment for the offence — where s 47(5) refers to a circumstance, two previous convictions for the same offence, which results in a greater maximum penalty — where accordingly s 47(5) did not require notice to be given of any of the respondent’s previous convictions for offences which were not offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 — where those previous convictions should have been taken into account by the Magistrate if and to the extent that they were material to the sentences to be imposed for the current offences — where the decision to the contrary in Washband should be overruled — where on the authority of The Queen v De Simoni (1981) 147 CLR 383, the inadmissibility of the two previous convictions could not be avoided merely by the prosecutor disclaiming reliance at the sentence hearing upon them as a circumstance rendering the respondent liable to the increased penalty of two years imprisonment — where the prosecutor asked the Magistrate to rely upon both convictions — where that was not open to the Magistrate — where the Magistrate was correct in holding that the evidence of the two previous convictions for offences against s 80(1) of the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 1989 should not be received but was in error in not taking into account the respondent’s other previous convictions — where the omission to take them into account may have had an effect upon the sentence, however it is not appropriate to reconsider the sentence or to grant leave for that purpose — where the respondent’s sentence was completed years before the application for leave to appeal was heard by this Court — whether the sentence was manifestly inadequate. Leave to appeal granted, appeal dismissed, applicant to pay the respondent’s costs.

Footnotes

61. Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd v State of Victoria (2002) 211 CLR 1, [50] per Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ “The position of the plaintiffs in the proceeding may be contrasted with those whom they represent – the group members. Subject to some exceptions that do not matter for present purposes, the consent of a person to be a group member is not required. Group members may neither know of the commencement of the proceeding nor wish that it be brought or prosecuted, although Pt 4A does provide for notice to be given to group members of (among other things) the commencement of the proceeding.”

62. see for example ss 33L and 33N

63. P Dawson Nominees Pty Ltd v Brookfield Multiplex Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 176, [16]

64. Thomas v Powercor Australia Ltd (Ruling No 1) [2010 VSC 489, [39].

65. [2002] FCA 1560

66. see for example [2011] VSC 401

67. Ibid [32] to [33]

68. Vincent Morabito, the Second Report, above n 5, 35; Paul Miller, ‘Shareholder class actions: Are they good for shareholders?’ (2012) 86 ALJ 633.

69. Nicholas Pace, Class Actions In The United States Of America (Globalisation of Class Actions Conference, Oxford University, 2007); Marc Galanter, ‘The Vanishing Trial: An Examination Of Trials And Related Matters In Federal And State Courts’ (2004) 1 J. Empirical Legal Stud., 459.

70. Ken Adams, Issues And Challenges In Resolving Class Actions (Commercial Law Conference, Supreme Court of Victoria, 2012).

71. Ibid [16] to [17].

72. [2010] VSC 489, [39]

73. Ibid [49]

74. [2012] VSCA 168

75. [2012] VSCA 221

76. Ibid [15].

77. [2013] FCA 115

78. There is though a question as to the basis of the respondent’s concerns that they may become unable to claim contribution from the class members’ financial advisors by effluxion of the limitation period (as accepted by Nicholas J). For example, s 24(4)(a)(i) of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) allows a contribution claim to be made at any time within which the action might have been commenced against the party seeking contribution. The relevant limitation period is six years for the causes of action under the Corporations Act. However the time limit is suspended for all class members by operation of s 33ZE of Pt IVA which provides: (i) Upon the commencement of a representative proceeding, the running of any limitation period that applies to the claim of a group member to which the proceeding relates is suspended. (ii) The limitation period does not begin to run again unless either the member opts out of the proceeding under section 33J or the proceeding, and any appeals arising from the proceeding, are determined without finally disposing of the group member’s claim.

79. [2001] 2 S.C.R. 534; 201 DLR 385

80. David Herr, Annotated Manual for Complex Litigation (Thomson West, 4th ed 2007)[21.41]

81. Thomas v Powercor Australia Ltd (Ruling No 1) [2010 VSC 489 [56] to [57] where Forrest J said: “…Powercor should be provided with sufficient information, relevant to the group members, to enable it to have some idea as to the size of the claim it has to meet in the event it is found liable to the group. As I have said, the provision of discovery by all group members is out of the question; however there should be a process by which Powercor can obtain such information in the form of particulars of loss and with accompanying substantiating documentation from, if possible, a representative sample of members.”

Footnotes

19. Section 33D of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 provides that in for the purpose of commencing a class action under Pat IVA a person who has a sufficient interest to commence a proceeding on his or her own behalf against another person has a sufficient interest to commence a representative proceeding against that other person on behalf of other persons. The threshold requirements of s 33C(1) are required to be satisfied. This provides that a class action may be commenced by one or more persons as representing some or all of the members of the class where: (a) 7 or more persons have claims against the same person; and (b) the claims of all those persons are in respect of, or arise out of, the same, similar or related circumstances; and (c) the claims of all those persons give rise to a substantial common issue of law or fact.

20. As to what is a ‘matter’, see e.g. Abebe v Commonwealth (1999) 197 CLR 510.

21. See e.g. s 33Q(2) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976.

22. See e.g. s 33Q(3) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976.

23. Section 33(1)(a) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976.

24. Nixon v Phillip Morris (Australia) Ltd (1999) 95 FCR 453

25. See e.g. Bray v Hoffmann LaâRoche (2003) 130 FCR 317; Mc Bride v Monzie Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1947 (Finkelstein J).

26. Civil Justice Review, Report No 14, Victorian Law Reform Commission, 2008, chapter 8

27. Ibid at 529.

28. Section 58 (2) Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW)

29. See e.g. the discussion of these issues in the recent judgment of Nicholas J in Hopkins v AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 115 [30]â[40]

30. See e.g. s 33C(1)(c) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976.

31. See e.g. Practice Note CM 17, Representative Proceedings Commenced under part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) 2.1

32. See Konneh v State of NSW [2011] NSWSC 1170.

33. See the decision of the Federal Court in Dorajay Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Leisure Ltd (2005) 147 FCR 394 (Stone J) and the decision of the Victorian Supreme Court in Rod Investments (Vic) Pty Ltd v Adam Clark [2005] VSC 449 (Hansen J).

34. See P Dawson Nominees Pty Ltd v Multiplex Limited [2007] FCAFC 200 (French, Lindgren and Jacobsen JJ).

35. See Kalajdzic J, Cashman P and Longmoore A, ‘Justice for Profit: A Comparative Analysis of Australian, Canadian and U.S. Third Party Litigation Funding’, The American Journal of Comparative Law [Vol. 61, 2013] 93.

36. In Pathway the Victorian Supreme Court recently ordered by consent that those who register as group members, rather than opt out, do so on the understanding that they will, if they are to receive any money on resolution, pay their share of costs and a percentage to the funder. The orders were made without debate about the source of the power: Pathway Investments Pty Ltd and others v National Australia Bank Ltd SCI 2010 06249, 24 August 2012

37. A number of these cases are referred to in the article referred to above.

38. See the discussion in the following cases: Williams v FAI Home Security Pty Ltd [199] FCA 1771; Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1123; Peter Hanne & Associates Pty Ltd v Village Life Limited [2008] FCA 719; Mathews v SPI Electricity Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] VSC 66.

39. See ss 33Q & R, Federal Court of Australia Act 1976

40. Section 43 (1A) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976

41. Cook v Pasminco (No 2) (2000) 107 FCR 44

42. See e.g. s 33K Federal Court of Australia Act 1976

43. Kelly v Willmott Forests Ltd (in liquidation) [2012] FCA 1446

44. See e.g. the following decisions: King v GIO Holdings Ltd [2002] FCA 1560; Hurley v McDonalds Australia Ltd [2001] FCA 209; Wright Rubber Products Pty Ltd v Bayer AG [2010] FCAFC 85; Meaden v Bell Potter Securities Ltd [2011] FCA 136; Kirby v Centro Properties Ltd [2011]; National Australia Bank Limited v Pathway Investments Pty Ltd [2012] VSCA 168; Regent Holdings Pty Ltd v State of Victoria [2012] VSCA 221; Winterford v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 1199; Hopkins v AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 115. See also Legg M, ‘Discovery and particulars of group members in class actions’ (2012) 36 Australian Bar Review 119â136

45. Hopkins v AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 115

46. Section 33ZE of the Federal Court of Australia 1976 (Cth) suspends limitation periods for group members from the date of commencement of the class action. Query whether or not this may keep alive the respondent’s right to make a cross claim pending a determination of each class members claim.

47. In Federal Court proceedings pursuant to s 33ZF(1) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976

48. See e.g. Courtney v Medtel Pty Ltd (2002) 122 FCR 168. In Courtney Sackville J held that while the respondent could communicate with group members in the circumstances of that case, where it was ‘communicating with a group member in a manner which is not misleading or otherwise unfair and which does not infringe any other law or ethical constraint’, the Court might intervene pursuant to s 33ZF where that was not the case (at 183 [52]). See also Pampered Paws Connection Pty Ltd v Pets Paradise Franchising (Qld) Pty Ltd (No 5) [2009] FCA 1053. See also Grave D, Adams K and Betts J, Class Actions in Australia, second edition, Law Book Company, 2012 at 14.310.

49. Federal Court, Practice Note CM 17âRepresentative Proceedings Commenced under Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976, 6. The respondents in a product liability class action concerning prosthetic hips recently instituted a ‘compensation regime’ outside of the class action (Stanford v DePuy and Johnson and Johnson Federal Court NSD213/2011) The applicants’ injunction application was dismissed by consent after the respondents agreed to deliver corrective information to affected group members.

Welcome to the March 2013 edition of Hearsay. This edition carries an article by branding specialist, Nicki Lloyd, of Lloyd Grey Design, about branding of the profession of barristers on the whole.

At our recent State Conference a paper was presented by Belinda Cohen, on what might be described as marketing for barristers individually.

Nicki Lloyd’s article is distinctly different however. Its focus is on the branding of the profession rather than the individuals within it.

As Ms Lloyd explains, a brand provides an emotional connection with its target audience. The audience for the bar as a profession are litigants (on each side of the case), solicitors and judges. Little as we may think of it in such a way, there is an emotional connection, for good or for bad, between each of them and the Bar. The Bar has a brand, whether we appreciate it or not.

Brands of course have to be nourished and maintained. They can also be developed or enhanced. Historically, in this country at least, these propositions have been, we here at Hearsay suspect, largely unappreciated, if not ignored.

Our President has recently written to the members of the Bar Association of Queensland advising of issues confronting the Bar and its place in our market and certain initiatives intended to advance the profession (http://www.qldbar.asn.au/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=232). Reading Ms Lloyd’s article may give some insight into some aspects of that strategic thinking that may be further developed.

The reality is that the Bar in this state (and probably in this country) has never really considered having a branding strategy, let alone put in place the resources to develop or manage the strategy. We here at Hearsay think that it is time we give it serious consideration.

In our view Ms Lloyd’s introduction to the concept of the branding of our profession is critical reading for those with an interest in the maintenance and advancement of the profession into the future. Pursuit of the ideas referred to in it by way of development and implementation of a strategy would be for the benefit of current members of the Bar and, as importantly, for the generations to come. We urge you to read it, and read it more than once, and reflect on the ideas within it.

Otherwise, in this month’s edition of Hearsay we have perhaps the finest collection of papers that we have been able to present in one edition in a long time. Gathered largely from the Australian Lawyers’ Alliance Conference recently held as well as our own State Conference, they canvas a wide range of fields and will deliver great value to the reader.

The quality of them and of the contributors is such that we are reluctant to single out any individual papers, but in the end we must commend especially to our readers the paper that was the keynote address at the State Conference by Lady Justice Rafferty DBE and the paper by Chief Justice Keane, as his Honour then was, from the ALA Conference entitled “Advocacy: The View from the Bench”. We are sure that the pre-eminence of those authors alone will compel you to read the pieces and you will be glad that you did.

We also have the usual miscellany including a number of book reviews, for which we take the occasion to especially thank Stephen Keim SC and his team for their regular contributions.

Happy Easter.

Geoffrey Diehm SC

Editor

You strike me as of widely differing seniority and I know your areas of practice differ too. Not to mention your incomes. Not to mention your genuine level of interest in this keynote speech. Thank goodness for the enduring politeness of today’s legal audience — I very much hope — important to someone like me, who stands before you with so many obvious deficiencies: not native Australian, first visit to the continent, old, boring, a lawyer, no amusing novelty value — really nothing for you to laugh at at all. That of course may shortly change, whether I like it or not. But stay strong, I have one hidden claim to presence here. We’ll come to it in due course.

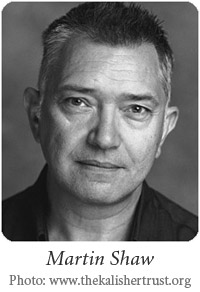

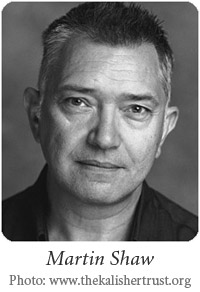

Last October in London the prestigious Kalisher Lecture was given by the actor Martin Shaw. He is both a Bencher of Gray’s Inn and, like me, a Kalisher trustee. Set up in 1996 to commemorate the outstandingly able and irreverently amusing Michael Kalisher QC — he could almost be Australain — it looks for talent from any background which would otherwise find the costs of training for the Bar prohibitive. His title was “Excellence is Through Industry Achieved” — hands up if you can name the play from which the quotation comes. No, neither could I. His central theme was support for the existence of a top layer of the best, rising through the ranks, recognized by virtue of star quality honed in the arena — the courts. He said:

Last October in London the prestigious Kalisher Lecture was given by the actor Martin Shaw. He is both a Bencher of Gray’s Inn and, like me, a Kalisher trustee. Set up in 1996 to commemorate the outstandingly able and irreverently amusing Michael Kalisher QC — he could almost be Australain — it looks for talent from any background which would otherwise find the costs of training for the Bar prohibitive. His title was “Excellence is Through Industry Achieved” — hands up if you can name the play from which the quotation comes. No, neither could I. His central theme was support for the existence of a top layer of the best, rising through the ranks, recognized by virtue of star quality honed in the arena — the courts. He said:

The court is an unforgiving crucible in which the competent survive, the inadequate dissolve, but the good are burnished. You all remember or still experience the toiling into the small hours mastering the brief, slogging to court, coping with someone unappealing, hostile, and less intelligent than you — and as well as the Judge, the defendant. Those are your training grounds. The attritional honing of your individual skills and style, in the arena, against an opponent.

The Bar is a profession of competitors. Against one another, against the odds, against the individual’s own notional 100%. Competition is the one sure guarantor of excellence. And Aristotle had a few thoughts: Excellence is an art won by training and habituation. We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.

It’s so simple to set out. It’s less simple to translate into how the legal profession functions or ought to function in 2013. In England and Wales (Wales is a country with connections to England going back hundreds of years but where what they’re saying is hard for the English to understand. The natives have mixed views on people from England. Sometimes they are welcoming, sometimes not. For the visitor it can be difficult to tell. Nervousness is common). As I was saying, in England and Wales we confront a time of financial constraint unknown before now. There is little money for the profession and all the indicators are that in 2014 and 2015 there will be less.

Consequently, not only are we in the age of instant communication and relentless pursuit of speed of response but also of trying to make those factors redound to our benefit against a backdrop of reduced and dwindling resource. The legal profession is flooded at the incomers’ end with youngsters who can call themselves barristers but who stand little chance of a pupillage, let alone a tenancy. Those who win a permanent place in chambers then face the next precipice: getting work. Those who stay in the profession face yet another: retaining work. In the crucible, the unforgiving now starts from Day One.

So, what to do? What advice to give the school-leaver deciding on a next step? There’s this: The cast of mind of a lawyer is useful across the piece. Lawyers think analytically, express themselves clearly, are careful bordering on the pedantic, and aim to get it right the first time because they know that clearing it up means the Court of Appeal. And time spent in the Court of Appeal is horrible. I should know. In 2013, when so much of society is dumbed down, the young are at risk of not expressing themselves well, or sometimes at all, let alone attractively — texting and social networking militate against it. But if they can think, write, and speak clearly they can skilfully advance or oppose a proposition.

It is the mark of the educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it. Aristotle again.

It is the mark of the educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it. Aristotle again.

Skills you have at your fingertips, which by now come naturally to you, will help them pass exams, get jobs, and do well in any interview. It means that when they speak they are unconsciously an ambassador for the life they have chosen. I agree with the actor Kevin Spacey. If you’ve been lucky and have made something of yourself within your chosen profession, it’s your duty to send the elevator back down. He’s colonial. I think he means “lift”.

Additionally, as Mr Shaw explained during the Kalisher lecture, in a small but collegiate profession, the trust and confidence of one advocate in another is crucial. “Being as straight as a die”- is key. The sharp, the dodgy, the “don’t turn your back on him” cannot hide. Everyone relies on this deep-seated tradition of probity, not least the Judges. They have neither opportunity nor time nor inclination to descend into the well of their court to unpick the behaviour of counsel. They must be able to consider the arguments, not concern themselves with what manner of man or woman advances them.

We are now in the business of ensuring that the 2013 and onwards legal profession continues to shine against the ordinary and, I’m afraid, there are obstacles. Standards, due to influx of number or other reasons can be lower than one would want, the young potential entrant is arguably paying to join a profession which can’t feed him/her, there is both reducing money and the white noise of competing public entities baying for their share of the pot.

Striking any chords?

I wonder if trials need to change their shape? In England and Wales we have modified and are modifying our attitude to the oral tradition, the change amounting to broad highways in civil and administrative procedure, country lanes in crime. There are two things in play: the attitudes of counsel and the mindset of the judge, and the prevailing mood of the meeting. A happy confluence of all three might make a major difference. Is it worth pulling back from the amount of time we spend ventilating issues in court? The first question I’d ask is whether the time we currently spend pays proportionate dividend. Let’s look together at some examples.

Economy of expression is always good. The Lord’s Prayer: 65 words. The Gettysburg Address: 258. The European Directive on Duck Egg Production: 12, 921. Economy of presentation is good – most of the time. There will always be occasions when some part of the case requires more rather than less and much of that is in the sense, the feel, of what’s happening. You know that. And you know when “more” is genuine, not a money-maker for the shyster.

Experts. We still, certainly in civil or in crime where we think a jury needs it, take an expert through his/her report in examination in chief. We are better now at translating the technical terms but we still tend to include the technical first and then explain it. It’s a small point but not I think insignificant because it shows mindset. “Cut” not “laceration” and “graze” not “abrasion” is a graceful concession to progress but really not best practice, more an acceptable second best. Is it?

We are increasingly good at locking experts in an airless room and making them reduce to an agreed document the areas in dispute. Do they need to be together? They need to communicate, but it is 2013, and there is e mail and the videocon. There are occasions when eyeballing the other chap is the best way but it isn’t always so. What’s wrong with a rebuttable presumption making the attendance of more than one expert the exception not the rule?

And if experts can do it why not some other category of witness? I am on my guard because I want to keep clear of appearing to suggest a move to an inquisitorial system. Foreigners cause enough problems already – I can see you thinking exactly that. But as so often there are aspects of another way of working which might withstand intelligent translation. Many more consequential questions in advance of a hearing? Once again in civil we are streets ahead of administrative law and of crime and exactly this is unexceptionally done. Not often enough, but done nevertheless. In crime if it’s happening at all it is the exception. But quite often, in a robbery or a personal injury fraud, whether the car were parked on the north or the south of the street matters but isn’t crucial. It’s which way it was facing and the line of sight that are important. Three disinterested householders one pedestrian and a passing motorist have to come to court and that may be unavoidable. We all know that setting the scene and settling the witness — or unsettling him, dependent on whom one represents — is often part of the skill and what counsel is paid for. But there are legion instances when either some need not come or, more often I suspect, might still have to come but the time spent in the witness box could be reduced. Trials cost money because time costs money. Reduce the time per contest and the advantage might seem so slight as not to justify the effort. But add up the saving over a year and nationwide and the picture might change.

Tablets. We are creeping — unconfidently — towards using tablets. It’s common now to see counsel with their Ipads, often alongside their achingly slender designer cutting-edge laptops, and the Court of Appeal Criminal Division is trying a pilot of ipad use instead of or as well as textbooks and reports. You like it or you don’t. You are prepared to try it or you’re not. You’re willing to kidnap a passing eight year old and learn how to use the thing, or you’re not. So far so good.