The ABA Journal website can be accessed at http://www.abajournal.com/

A selection of recent items are listed below and members are invited to explore the vast array of articles that are continually posted.

Trial observer who took photo of victim in high-profile case wins motion to suppress phone search.

This article raises some of the issues that can attend the advance of mobile phone technology into court rooms. It is a case of an observer at a high profile trial who took a photo of a victim in a high-profile sexual abuse case using a mobile phone. The trial judge had earlier ordered that no photos be taken. A court officer suspected that the owner of the phone had taken a photo of him, so he seized the phone to check. The court officer found no photo of himself, but did find the offending photo of the sexual abuse victim taken in contravention of the order. The owner of the phone succeeded in having the contents of the phone suppressed, as the court officer did not have a warrant to search it.

View blog

Law firms that sued HP want to represent it as part of settlement; objecting lawyer says deal a joke

This item reminds us that the imagination of many lawyers knows no bounds. It involves the court refusing to sanction an agreement settling a suit against Hewlett Packard in which the plaintiff’s lawyers had inserted a term requiring HP to engage them for future litigation at fees of up to US$48 million. One other lawyer said of the proposed deal: “If it was a carcass, animals would walk around it, it stinks so much”. The court apparently agreed.

View blog

Looking back on Zubulake, 10 years later

This article “Looking back on Zubulake, 10 years later” looks at the Zubulake decision, that broke new ground for the obligations of lawyers to seek out and preserve documents (most notably electronically stored documents) for discovery.

View blog

Another article, from the Michigan Bar Journal, discussing the decision may be accessed here:

View blog

What judges really think of the phrase “May it please the court”:

View blog

Edward Pollentine & Anor v The Honourable Jarrod Pieter Bleijie Attorney-General for the State of Queensland & Ors [2014] HCA 30

Today the High Court unanimously upheld the validity of s 18 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1945 (Q) which allows a trial judge to make directions for the indefinite detention of a person found guilty of an offence of a sexual nature committed upon or in relation to a child.

Section 18 of the Act provides that a judge presiding at the trial of a person found guilty of an offence of a sexual nature committed upon or in relation to a child may direct that two or more medical practitioners inquire as to the mental condition of the offender, and in particular whether the offender “is incapable of exercising proper control over the offender’s sexual instincts”. The section provides that if the medical practitioners report to the judge that the offender “is incapable of exercising proper control over the offender’s sexual instincts”, the judge may, either in addition to or in lieu of imposing any other sentence, declare that the offender is so incapable and direct that the offender be detained in an institution “during Her Majesty’s pleasure”. An offender the subject of a direction to detain is not to be released until the Governor in Council is satisfied on the further report of two medical practitioners that it “is expedient to release the offender”.

In 1984 Edward Pollentine and Errol George Radan each pleaded guilty in the District Court of Queensland of sexual offences committed against children. In each case, on the report of two medical practitioners, the District Court declared that Mr Pollentine and Mr Radan were incapable of exercising proper control over their sexual instincts and directed that they be detained in an institution during Her Majesty’s pleasure. Mr Pollentine and Mr Radan brought proceedings in the original jurisdiction of the High Court challenging the validity of s 18 of the Act on the ground that it was repugnant to or incompatible with the institutional integrity of the District Court, thereby infringing Ch III of the Constitution.

The High Court upheld the validity of the provision. The Court held that while a court may direct the detention but not the release of an offender under s 18, the court has discretion whether to direct detention. Furthermore, release of an offender is not subject to the unconfined discretion of the Executive and does not lack sufficient safeguards. Rather, a decision to release is dependent upon medical opinion about the risk of an offender reoffending, and the decision is subject to judicial review. The Court held that the provision is not repugnant to or incompatible with that institutional integrity of the State courts which bespeaks their constitutionally mandated position in the Australian legal system.

Anthony Charles Honeysett v The Queen [2014] HCA 29

Today the High Court unanimously allowed an appeal brought by Anthony Charles Honeysett against his conviction for armed robbery.

In 2011, Mr Honeysett was convicted following a trial by jury in the District Court of New South Wales of the armed robbery of an employee of a suburban hotel. The robbery was recorded by closed-circuit television cameras (“CCTV”). The head and face of one of the robbers (“Offender One”) was covered, as was the remainder of Offender One’s body, save for a small gap between sleeve and glove. At trial, over objection, the prosecution adduced evidence from an anatomist, Professor Henneberg, of anatomical characteristics that were common to Mr Honeysett and Offender One. Professor Henneberg’s identification of these characteristics was based on looking at the CCTV footage of the robbery and at images of Mr Honeysett taken while he was in police custody.

Mr Honeysett appealed against his conviction to the Court of Criminal Appeal of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, submitting that Professor Henneberg’s evidence was inadmissible evidence of opinion. The Court of Criminal Appeal agreed with the trial judge that Professor Henneberg’s evidence was admissible because it was evidence of an opinion that was wholly or substantially based on his “specialised knowledge” within the meaning of s 79(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW). The Court accepted that Professor Henneberg’s specialised knowledge was based on his study of anatomy and his experience in viewing CCTV images.

By special leave, Mr Honeysett appealed to the High Court. On the hearing of the appeal, the prosecution did not maintain that Professor Henneberg had specialised knowledge based on his experience in viewing CCTV images. The prosecution relied solely on Professor Henneberg’s knowledge of anatomy. The Court held that Professor Henneberg’s opinion was not based wholly or substantially on his knowledge of anatomy: his opinion regarding each of the characteristics of Offender One was based on his subjective impression of what he saw when he looked at the images. As Professor Henneberg’s opinion did not fall within the exception in s 79(1), the Court held that it was an error of law to admit the evidence. The Court quashed Mr Honeysett’s conviction and ordered a new trial.

Daniel Glenn Fitzgerald v The Queen [2014] HCA 28

On 19 June 2014, the High Court unanimously allowed an appeal against a decision of the Court of Criminal Appeal of the Supreme Court of South Australia, which had upheld the appellant’s convictions for murder and aggravated causing serious harm with intent to cause serious harm contrary to ss 11 and 23(1) respectively of the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA). The High Court allowed the appeal, quashed the appellant’s convictions and directed that a judgment and verdict of acquittal be entered. Today, the High Court delivered reasons for making those orders.

On 19 June 2011, a group of men forced their way into a house in Elizabeth South in South Australia and attacked two of the occupants with weapons including a gardening fork and a pole. One victim died four days after the attack and another sustained serious brain injuries. After a trial before a judge and jury in the Supreme Court of South Australia, the appellant was convicted and was sentenced to a term of life imprisonment with a non-parole period of 20 years.

At the appellant’s trial, the prosecution contended that the appellant was a member of the group that had forced entry into the house armed with weapons and was a party to a common plan to cause grievous bodily harm to persons inside the house. There was no direct evidence that the appellant inflicted harm on the deceased or the other victim. The prosecution relied on DNA evidence obtained from a sample taken from a didgeridoo found at the crime scene to establish the appellant’s involvement in the attack. The prosecution’s circumstantial case was that the DNA in the sample derived from the appellant’s blood and was transferred by him to the didgeridoo at the time of the attack. The appellant argued that alternative hypotheses consistent with his innocence were open on the evidence. One such hypothesis was that a member of the group who was present at the crime scene had transferred the appellant’s DNA onto the didgeridoo, after the two men shook hands the night before the attack.

The appellant appealed unsuccessfully against his convictions to the Court of Criminal Appeal, arguing that the verdicts were unreasonable and could not be supported by the evidence. By special leave, the appellant appealed to the High Court.

The High Court unanimously held that the prosecution’s main contention, that the appellant’s DNA in the sample obtained from the didgeridoo derived from his blood, was not made out beyond reasonable doubt. Further, the recovery of the appellant’s DNA from the didgeridoo did not raise any inference about the time when or circumstances in which the DNA was deposited there. The Court held that it could not be accepted that the evidence relied on by the prosecution was sufficient to establish beyond reasonable doubt that the appellant was present at, and participated in, the attack. The jury, acting reasonably, should have entertained a reasonable doubt as to the appellant’s guilt. As the evidence was not capable of supporting the appellant’s conviction for either offence, no question of an order for a new trial arose.

Given in the Banco Court, at the official opening of the Path to Abolition, a History of Execution in Queensland — 18 June 20141

I was very humbled to be invited to speak at this event, because I am not much of a history scholar. Much of what I read in preparation for this evening was new to me.

Before being invited to speak tonight, I did not know that Queensland was the first state in the British Empire to abolish capital punishment – the first state in the Empire to make this humanitarian and socially sophisticated move.

And as a Queenslander that made me proud.

So, expanding on the theme of this exhibition — the path to abolition — I wanted to look into what it was that drove Queensland to take this step — what provided the impetus for this significant change.

I have been helped greatly in preparing for tonight by the library and its excellent researchers — in particular Adam Connolly and Zack George — and by my own excellent researcher Jemima Welsh.

The materials I’ve drawn upon include a published thesis by Ross Barber, from 1967, which was part of his Honours degree in Government, entitled Capital Punishment in Queensland and an article by Mr Anthony Morris QC, from 2002, about the Trial of the Kenniff Brothers; Australia’s last bushrangers.

The other source of my content for this evening has been the newspaper reports from the 18 and 1900s about the trials which led to executions in Queensland and about the executions themselves – which were obtained for me by the library.

I found in those reports opinions about the skill of trial judges, comments and opinions about the skill or otherwise of the executioner and an emphasis on the conversion to Christianity of the condemned at the gallows. I found often a report of an execution accompanied the details of a confession said to have been made by the prisoner to prisoner warders before their death, in what seemed to be an attempt at proving that the execution was justified. And there was often a comment at the end of an article that the process of execution itself was a sad and ghastly affair.

But what struck me most about the articles on executions was how matter-of-factly they were reported and the inclusion in the reports of details of the death and the deceased’s final seconds of life in a way which would be considered, I thought, too macabre for today.

And when I checked that idea by looking at current reports of executions in other parts of the world, I found that it was very rare for the detail of the manner of death to be included.

The change in the content and nature of the reports of executions, for Australian consumption at least, of course reflects the change in the thinking of the community about capital punishment at the different times. Then it was thought to be a distasteful necessity. Now, there is recognition that capital punishment is abhorrent to human dignity and there is no desire or demand for details of the executions.

Coming back to the path to abolition in Queensland and the impetus for change — it will come as no surprise to you that they were many factors at play. And as with almost all social change, it took the abolition movement some time to achieve its goal.

It seems to me that in Queensland, abolition was achieved at a time when there was a coincidence of, or a coexistence, of

- majority, though slim majority, political will in favour of abolition — of course;

- public sentiment in favour of abolition; and

- and enough favourable media.

So we find in the years leading up to abolition —

- Queensland politicians passionate about it & ultimately in a position to do something about it;

- a growing unease or moral discomfort about capital punishment in the community & a desire to become, or to be seen to be, more sophisticated and less barbaric;

- And then one or two hangings which particularly troubled the consciences of many;

It was in that environment that abolition was achieved.

The Act which abolished the death penalty in Queensland, the Criminal Code Amendment Act, received Royal Assent on the 31st of July 1922.

Ted Theodore was the premier at the time, having succeeded TJ Ryan, who’d moved on to Federal politics in 1919. The Labor party had been in power in Queensland since 1915.

A good ‘point’ on the path to abolition to start consideration of the political impetus for change is the mid 1890s — so just before Federation, with Queensland having been a separate colony since 1859.

By the mid-1890s, there had already been a significant winding back of the offences which attracted a death sentence.

By the mid-1890s, the arguments in favour of capital punishment had evolved beyond those which focused on revenge — the life for a life arguments — to those which focused on what was said to be its deterrent effect.

At that time, in all but the most brutal cases, arguments were made, usually successfully, particularly in the cases of white Australians, for commutation of the death sentence to one of imprisonment for life.

In 1899, the Criminal Code Bill was introduced into the Queensland Parliament.

At that time, the majority of the Parliamentary Labor Party was opposed to the abolition of capital punishment, although in the years immediately before its introduction, there had been no executions in Queensland.

The Criminal Code Bill proposed that rape and armed robbery with wounding be removed from the list of capital offences but it retained the death penalty for murder and a couple of other offences like treason.

The public mood at the time was against the execution of persons for murder which was not premeditated. This prompted Sir Samuel Griffith to draw a distinction in the draft code between murder and wilful murder. Wiful murder was a killing with an intention to kill. At its simplest, murder was a killing with an intention to inflict some grievous bodily harm.

Sir Samuel Griffith proposed that in the case of a conviction for a murder other than a willful murder, the sentence of death could be ‘recorded instead of being actually passed’ as was then the case in almost every other capital case.

The distinction between murder and wilful murder was adopted in the Code as passed, and the original section 652 of the Code permitted a sentencing Court, in the case of any capital offence, except treason or wilful murder, to record rather than pass a judgment of death where the Court thought it was proper that the offender be recommended for Royal mercy. That was the means by which the Court could convey its evaluation of the offence to the government.

The first member of the Queensland Parliament to call for more than just a winding back of capital punishment and to call for its total abolition was Joe Lesina, who gave the first speech in response to the Attorney General’s second reading speech relating to the Criminal Code Bill.

He was then a lone voice without support from influential members of the Labor movement. He spoke for two hours against what he called judicial murder.

He began his speech by talking about the gradual reduction in capital offences which had taken place over the century and reforms in European states.

He suggested that there had been an elevation in the moral tone of society — which allowed him to appeal for the abolition of the last vestiges of punishment by mutilation — the lash and the gallows.

And he continued (these are extracts):

I am opposed to these punishments because they are forms of mutilation and are altogether foreign to civilized ideas of punishment.

Our punishment today is largely punitive instead of being reformative. Instead of hanging criminals we should place them in correctional institutions.

The purpose of punishment should be to cure the offender. The criminal is not a wild beast. My view of him is that he is an erring brother whose feet have wandered from the narrow path which we all weakly strive to follow. Undoubtedly he must be punished, but to take his life is not the way to cure him.

Crime is largely a social product – it is the outcome of our present social conditions. It’s greatest breeding grounds are the highly centralised cities of modern industrialized society

Poverty and ignorance are the chief causes of crime.

The alteration of our social and industrial conditions are reforming influences which will have the effect of reducing crime.

I say that murder is just as much murder when authorised and directed by the executive as when it is committed on cold-blood by the private individual.

He also said:

If I should fail it is only I who have failed [for] somebody else as surely as the sun will rise tomorrow will take the matter up where I leave it. I feel perfectly sure that it will not be many years longer before the humanitarian feeling which is now spreading through this colony, and all civilized countries, will demand once and for all the abolition of the death penalty.

We hear in that language appeals to humanitarian ideals and a plea for a civilized approach to punishment in Queensland.

To test Mr Lesina’s statement about the elevation of the moral tone of society, I looked at the newspaper reports from the 1860s onwards. And what I found, generally, supported that observation.

Execution was considered at the least a distasteful practice and there was a certain respect in the reports for those who gave it an aura of respectability — so respect for priests and clergy who saved the soul of the condemned, respect prisoners who were calm and brave, an respect for hangmen who performed the execution ‘well’.

On the whole though the reports of executions were matter-of-fact and only in rare cases given prominence.

In newspapers for colonies outside Queensland, there were usually single columns dealing with the news from other colonies or States — and it was not unusual to find a brief report of an execution in Queensland followed immediately by a report about the Queensland weather and the shipping news.

In Queensland itself, for example, in 1864, a report of the death sentence passed on Alexander Richie was sandwiched between reports about the Warwick races, a police officer being given a gold watch and an evening tea meeting of the ladies of the Wesleyan denomination.

Some reports included what the condemned person had for breakfast on the morning of their execution and almost all commented on their demeanor — whether they were composed or anxious. And as I said, there was respect paid to those who accepted their punishment calmly or who ‘walked firmly’ to the scaffold or who ‘bore themselves well’ and much time spent on the conversion of the condemned and the saving of their soul.

The articles include reports of sentencing judges speaking of their duty in passing the death penalty as a painful one – of it being not their sentence but the sentence required by law – reports about sentencing judges being deeply affected and praying in Court that God would have mercy on the soul of the prisoner.

Side-tracking just a little — there was one particularly commentary which caught my eye. In 1872, the Brisbane Courier said that the judge in the trial of Patrick Collins summed up in a ‘masterful manner’, and after 35 minutes, Collins was convicted of murder. And about that same case, the Queensland Times said that the case had been ‘so wonderfully got up by the Crown’ that anything but a conviction was out of the question.

But mostly, the articles conveyed repugnance. The condemned were referred to as unfortunate or miserable, weak-minded, neglected or misguided.

In 1865, the Courier described the execution of Rudolph Mourberger as a disgusting ceremony and added that it was rendered more so by the cool and off-hand way in which the hangman performed his duty. In 1868, the Courier referred to a hangman making his ghastly preparations. In 1870 the Courier called a hangman disgustingly brusque and officious ‘and rather to relish the work before him’. In the 1870s, the Darling Downs Gazette referred to the morbid taste of the multitude.

So we do find the elevation in moral tone detected by Mr Lesina — though as I said, he was then without much support.

It has been suggested that one reason for the lack of support was that Labor then stood for a White Australia and many members of the Labor movement were then hostile towards ‘coloured aliens’ — in particular, Kanakas (workers imported from the Pacific Islands) and the Chinese because they were an economic threat to white laborers and to unionism.

There was a disproportionately high crime and execution rate among Kanakas and a point to be made about the corrupting influence of Kanakas at each execution.

Even after the passing of Federal legislation which terminated the transportation of Kanakas to Australia there was a tendency to ignore the executions of Kanakas and Chinese.

It was more effective to publicly protest against capital punishment when it was possible to generate public discontent — or to take advantage of existing public discontent — about the person to be executed.

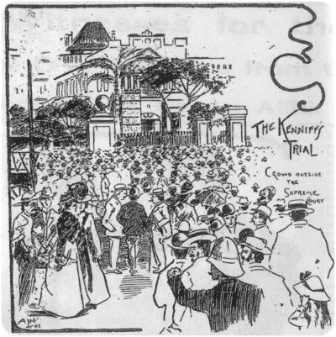

And that can be seen in the case of the Kenniff Brothers — an example which particularly invigorated public opposition to capital punishment.

The Kenniff brothers – James and Patrick – were horse stealers from Roma.

In 1902, they were pursued by police and indigenous trackers and James was caught.

He was bound and left with two police officers while the rest of the police and the trackers continued to hunt for Patrick.

They could not find Patrick & when they returned to where James and the two police officers had been left, no one was there — although there were bullet marks in surrounding trees and indications that human remains had been burnt.

After a massive man hunt, James and Patrick were arrested and charged with murder of the two police officers.

The brothers were not tried in Roma — as would have been usual — instead they were brought to Brisbane.

Their trial was before the Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Griffith — but instead of being tried by a jury of 12, they were tried by a special jury of 4.

From left: Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith, Justice Sir Pope Cooper, Justice Patrick Real, Justice Charles Chubb

Legislation existed which permitted the Crown to apply for a special jury rather than a common jury. A special jury was not a jury selected randomly, but rather a jury made up of affluent people like property owners or business men.

The idea behind special juries was that they might be required in cases of particular complexity. One of the complexities relied upon by the Crown in this case was that the evidence against the brothers was circumstantial. But it was of course likely that men of the class included in special juries would have no sympathy for the Kenniffs.

The brothers had no barrister at trial. They were represented a solicitor. They were both convicted — in about an hour — of wilful murder.

At that time, there could be no appeal from that verdict, but instead, questions of law could be reserved to the Full Court.

A report of their trial and the verdicts included this:

When, after an hour, the jury returned

with their verdict, the prisoners were visibly

nervous. The jury announced that they

found both the prisoners guilty.

Patrick Kenniff was asked had he anything

to say before sentence was passed. ‘Yes,’

he said, in a husky voice, ” I know the

sentence that is going to be passed on me.

Before your Honor passes it, I would like

you to understand that I am an innocent

man. I hope before you depart from this

world that you will find I am an innocent

man.”

James Kenniff was then asked if he had

anything to say. He replied : Yes, your

Honor, I wish to comment upon your summ-

ing up to day. You never gave us one atom

of justice. I have no other witnesses to

call, except Almighty God, to show that I

am an innocent man to-day. I hope when

your Honor shuffles off this mortal coil you

will find I am an innocent man.”

The Chief Justice then intimated to Mr.

M’Grath, prisoners’ counsel that he would

reserve to the Full Court counsel’s points,

namely, that there was no evidence to go to

the jury that the prisoners committed the

murder.

…

Addressing the prisoners, he said he entire-

ly agreed with the verdict of the jury. His

Honor them donned the black cap and passed

sentence of death, adding that the execution

would be respited pending the result of the

appeal to the Full Court.

The prisoners heard the sentence in sil-

ence. They looked at each other, and ex-

changed a few words. Before leaving the

dock they briefly conversed with their coun-

sel, and also shook hands with his business

partner. The prisoners walked from the

dock with firm steps.

Although the Chief Justice told the jury that he entirely agreed with their verdict, he sat, with three other Justices, on the Full Court to determine the questions referred.

The four Justices agreed that there was sufficient evidence to convict Patrick Kenniff.

Three of the four Justices agreed that there was sufficient evidence to convicted James — but Justice Real, in a strong dissent, argued that the police officers may have been shot while Patrick tried to free James, and without James being involved at all.

One of the papers described Justice Real’s dissent as a small detail in an otherwise unanimous conclusion about guilt — but the public did not miss that small detail.

There had been already public concern about the venue for the trial, the special jury, and the newspapers effectively convicting the Kenniffs even before they were arrested.

There was a concert held to raise money for an appeal to the Privy Council — Joe Lesina arguing that murder had not been clearly proven in the case.

Petitions were signed in Rockhampton, Brisbane, Toowoomba, Charters Towers and Townsville.

On the 24th of December 1902, the brothers’ solicitor informed Premier Philp that there would be a petition to the King-in-Council seeking permission to appeal to the Privy Council. On the 31st of December, then Executive Counsel announced that the sentence imposed upon James would be commuted to life imprisonment but that Patrick would be hanged on the 12th of January.

The Government’s attitude, as reported in the Courier, was that it was not controlled by any intention on the part of the prisoners to appeal.

But this show of force or determination, in the case of these men, just served to strengthen the position of the abolitionists in Queensland.

Patrick abandoned his appeal, because he would have been dead before any reply from England.

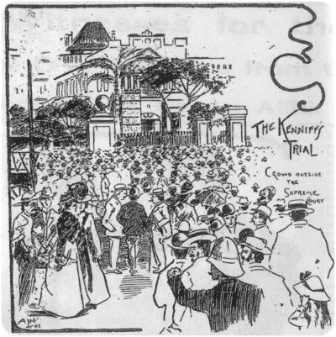

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause.

Despite petitions and deputations and 4000 people standing in heavy rain to hear Joe Lesina speak about how justice would suffer were the execution not postponed — the government — supported by the Courier — was immovable. As a consequence the Kenniffs became heroes and martyrs — ‘poster boys’ for the abolitionists’ cause.

So too Arthur Ross, who in 1909 was convicted of the murder of a bank teller. He was 21 and the jury had expressly acquitted him of willful murder and strongly recommended mercy because he was so young. Nevertheless, the government decided to execute him.

On the Saturday before his execution, Albert Hall was filled to overflowing with people calling for the commutation of his death sentence. Petitions containing thousands of signatures were presented to the Governor. A deputation was made to the Premier said to be on behalf of all classes of the community.

The Premier’s reply — that the gallows were a bulwark of society was met with scorn by the Worker – which was the newspaper affiliated with the Labor party — and you will see in the exhibition downstairs the front page of the edition containing the cartoon which was part of the response of the Worker to that comment.

The Worker’s editorial response included this statement — that:

the time has arrived for the enlightened modern spirit to repudiate the grisley gospel of the gallows —

and the editors also praised as a ‘manly and enlightened deliverance’ a sermon by a Methodist minister in favour of the abolition of capital punishment, which had attracted a large crowd.

Less than a year after the execution of Arthur Ross, the sixth Labor-in-Politics convention was held. By now, abolitionists had influence in the party — and without debate, a motion that the abolition of capital punishment should become part of the Party’s general program under the heading of social reform was accepted.

The inner-party battle was won at a time which seemed to coincide with a step up in public opinion in support of abolition. But the issue really lay dormant until Labor was victorious at the polls in 1915.

There was an attempt to abolish capital punishment in 1916 by the deputy minister for justice. I won’t go into the detail of it — other than to say that it was defeated in the Legislative Council and in any event the public were not particularly interested in it — perhaps because there had been no executions since Labor assumed power.

More momentum built from about 1920.

At the Labor-in-Politics convention then, abolition was elevated to the leading plank in the party’s social reform platform.

By 1921, there were sufficient supporters nominated to the Legislative Council for it to abolish itself.

The first unicameral Parliament opened in Queensland in 1922 & the Labor government immediately introduced the Bill to abolish capital punishment.

In April of that year, when a child murderer was hanged in Melbourne, the Worker ensured that the Labor party’s political agenda was complemented by carrying a feature article calling for the abolition of capital punishment accompanied by an emotive cartoon about the horror of execution — and that cartoon is in the display.

Clearly, the time was ripe & the bill passed by 33 votes to 30.

Statements made against the Bill were to the effect that the Executive could use their prerogative to deal with doubtful convictions, but those who violently killed were a cancer of society and the only thing to do with them was to get them out of the road. It was argued that violent killers were afraid of death and that fear was their greatest deterrent.

Part of the argument of the then Attorney General, John Mullan, in support of abolition included this:

Hanging has proved to be a failure; it is merely a survival of the primitive instinct for revenge and it is time that capital punishment was abolished. We should be more humane and adopt a more humane method. A more humane method would be to inflict the penalty of imprisonment for life. I believe that, as a result of more humane laws in connection with this matter, and more humane methods generally, and more liberal education, together with an improvement in our social conditions, we will do more to mitigate and eliminate horrible crimes than we can do by other means.

As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.

As we know, the bill passed and received Royal Assent on the 31st of July, and the hangman was shown the exit as depicted in the cartoon on the front page of the Worker on July 27, 1922, which is the last piece in the exhibition downstairs.

So with slim majority political will and power and an elevation in moral tone and compassion and humanism in the community and martyrs to the cause, Queensland became the first State in the British Empire to abolish capital punishment.

Thank you.

Soraya Ryan QC

Intro image (top): James and Patrick Kenniff

Stetch: Crowds gathered outside the Supreme Court building in George Street, Brisbane, for the Kenniff trial – from Sunday Truth newspaper, 9 November 1902

Photograph right (bottom): The Hon Justice Hugh Fraser, Soraya Ryan QC and the Hon IDF Callinan AC QC taken at the Oration to open the Supreme Court Library’s Path to Abolition exhibition in the Sir Harry Gibbs Legal Heritage Centre.

Cedric Edward Keid Hampson was born in Ashgrove on 18 January 1933 and passed away in the embrace of his family at his beloved home in Ascot last Saturday, aged 81.

It is not the length of life that matters, but the depth. By any measure, Cedric Hampson lived a deep life.

Cedric’s early life

Cedric was the eldest of three children, with brother Lester and sister Rhonda who are present here today.

During his primary schooling at St Finbarr’s School, Ashgrove he was identified as a child of unusual ability. In his unfinished memoirs [to which I have been granted privileged access] Cedric recalls that in a two year period in grades 1 and 2, he read every book in the school library.

From grade four, he was educated at St Joseph’s Gregory Terrace usually being dux of his class but never less than third. He maintained a lifelong interest in supporting his old school.

Cedric took degrees in Arts and Laws at the University of Queensland where he was President of the student body and represented the university in debating and rugby. Based upon his academic brilliance and sporting prowess, Cedric was selected in 1955 as a Rhodes Scholar and undertook his Bachelor in Civil Laws at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he rowed and continued to play representative rugby.

At dinner at college after an expansive day enjoying the rugby Cedric became concerned that one side of his face was very hot and flushed, only to come to the realization that his head had fallen into the soup.

Marriage and family life

Whilst at Oxford he went on a skiing trip to Austria with a couple of mates where he met and immediately fell in love with the beautiful Catharina Brans Kremers from Amsterdam. After five days he proposed. As Catharina was the apple of her father’s eye, letters were dispatched post haste to the Archbishop in Brisbane and to the Principal at Gregory Terrace inquiring after the credentials of this wild bearded man from Australia. Apparently the response was positive as, six months later, they married with the blessing of Catharina’s family.

Cedric brought his young bride back to Australia to share the privations of a frugal existence in an abode in Auchenflower where their first bed was made from an old door as Cedric worked hard to establish his career at the Queensland Bar.

This loving union produced four very accomplished children, and 10 handsome grandchildren — Oscar, Hugo, Sophie, Casper, Harry, Greta, Eddie, Ava, Jonno and Violette.

While raising her family, Catharina managed to establish herself as a celebrated sculptor and artist, with one of her works gracing the foyer of the Inns of Court. It is surely not entirely coincidental that the depicted passionate advocate in wig and gown pleading for the hapless family bears a striking resemblance to Cedric.

Cedric and Catharina’s elder daughter, Dr. Edith Hampson, has distinguished herself in academic circles as a veterinary scientist. Their younger daughter, Alice, is a highly respected prize winning architect. Their elder son, Leofric, is a member of the Bars of Queensland, England and Wales, and Brussels, practicing in Brussels in European Union business law. Their younger son, Edmund, a graduate of the Queensland University of Technology in building science, has established a successful business in the construction industry.

I warmly acknowledge the presence today of the partners of Edith, Alice and Edmund, namely, Peter Clark-Ryan, Anthony Morris QC and Pepita Hampson.

One of the fondest childhood memories of the children are of life with Cedric at the family macadamia nut farm at Landsborough.

Cedric and Catharina’s younger daughter Alice considers that the twilight years with Cedric were the sweetest for her; a time for sharing both the poignant and the simple moments. Alice recalls that Cedric attended the ultrasound scan of her child Violette in utero and marvelled about how formed and perfect she was at only 18 weeks – “a person” Cedric declared.

In those twilight years, Cedric could enjoy the simple pleasures of life like coffee from every single coffee shop in the neighbourhood; the cafes, the smaller “hole in the wall” type establishments, the businesses with a sideline in coffee, including grocery shops like Sirianis’, even service stations and a family law office at Albion. He knew the coffee from all of them, but his favourite was the coffee from the St Margaret’s tuckshop, especially if it came with a little gingerbread treat.

In these years Cedric’s greatest pleasure came from spending time with his grandchildren. Last evening I was much moved to hear some of Cedric and Catharina’s grandchildren express the love and the deep affection they had for their Opi.

Cedric’s legal career

At the height of his legal practice, Cedric bestrode the Queensland Bar like a colossus.

In his unfinished memoirs, Cedric recalls:

“I was going to be a Priest, a doctor or a lawyer. They were the three choices…………I think my mother wanted me to be a priest.”

Cedric was called to the Bar in 1957 and the Senior Bar in 1971.

He was President of the Queensland Bar Association from 1978 to 1981, and again in 1995 to 1996.

A perusal of the Commonwealth Law Reports and the Queensland Reports since the early 1960s readily demonstrates, not only the huge number of cases in which he appeared, but also the extraordinary diversity of those cases – crime, personal injuries, defamation, commercial and industrial matters, town planning cases, property disputes, and constitutional matters.

It is not only the volume and diversity of cases that is remarkable, but the range of Courts and Tribunals he appeared before.

The Privy Council in London, the High Court of Australia, the Federal Court, the Family Court, the full range of Queensland courts – the Court of Appeal, the Supreme Court, the District Courts, the Magistrates Court and various Tribunals.

Cedric was a true generalist with an amazing breath of legal knowledge and forensic skills. More broadly, he seemed to have a wealth of knowledge about any subject.

In the 70s and 80s, Cedric was regarded as the alpha male of the Queensland Bar.

Counsel regarded a junior brief to Cedric as “like going to Court with your father, nothing can go wrong.”

The rule of thumb for Bar Association deliberations for decades was “what would Cedric do in this situation”.

The Inns of Court, at the corner of North Quay and Turbot Street, stands as a testament to Cedric Hampson’s initiative, foresight and organizational skills. Cedric was Chairman of Barristers Chambers Limited from 1973 to 2006, Chairman of the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting from 1973, and Chairman of the Management Committee of the Bar Practice Centre from 1983 to 1989.

“If you seek my monument”, Sir Christopher Wren declared, “then look around you.” Cedric was not only a leader but a builder of the fabric of the Queensland Bar.

The day before Cedric’s death, the Board of Directors of Barristers Chambers Limited — knowing that Cedric’s health was failing — met, and decided that his immense contribution to the home of the Queensland Bar had not yet been adequately recognised. Although a meeting room in the building is already named in his honour — as is the group of chambers on the 17th Level where Cedric once had his room — a further and more substantial tribute was considered appropriate. Sadly, Cedric did not live to be informed by his successor as Chairman, David Tait QC, about this last of many richly-deserved accolades: the proposed renaming of the Inns of Court Bar Common Room in his honour.

My knowledge of Cedric

At the very peak of his career, when many barristers could be forgiven for relaxing into the routine of an established practice, Cedric’s work as a barrister took a new turn: he became something of a Royal Commission and Public Inquiry specialist. He liked the work. He once explained that it took him out of the constraints of court life and exposed him to people and issues that he would not meet or deal with otherwise.

I first worked with Cedric as a junior Melbourne based lawyer on the national Royal Commission into Drugs chaired by the late Justice, Sir Edward “Ned”, Williams at a time when Cedric was President of the Bar Association. Cedric was Senior Counsel Assisting. I was immediately struck by the courtesy and consideration which he showed to his instructing solicitors, his clients, and his junior barristers. In a 20 year working association, I never observed even the slightest hint of arrogance in his dealings with me or any of the other subordinate personnel. I was also to learn and experience that he was the most generous of hosts.

Sir Edward and Cedric were the perfect team. Sir Edward was full of drive, energy and enthusiasm while Cedric methodically put the Inquiry organization and structure in place. From the first day of the first hearing in a two year inquiry, Cedric was shaping the final report — with issues identified and chapter headings assigned — to be progressively modified as the evidence was received and analysed.

The resultant report on Drugs in Australia was a monumental work of five volumes with the cover designed by Cedric showing Australia breaking apart along its state jurisdictional borders. The Inquiry recommendations led to massive changes to Australian law enforcement and to drug control, for example, the establishment of the Australian Federal Police and the creation of the Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence, to deal nationally, for the first time, with the threat posed by Organised Crime to the Australian community .

Cedric didn’t always have things his own way. While touring the drug production countries in Central and South America, Cedric suggested to Sir Edward that they should take up the invitation of the Mexican Attorney-General to fly over some clandestine drug crops in the mountains so that they could appreciate at firsthand what a law enforcement challenge they represented. As the helicopter crested a ridge and a drug crop in the valley came into view, the crop sitters took umbrage at being spied on by the federales. A bullet ricocheted off one of the rotor blades and the guards on board returned fire. At this point, Cedric began to wonder about the wisdom of his recommendation.

A year or two later I took up the same assisting role when Cedric was appointed to the national Royal Commission into Drug Trafficking [ known colloquially as the Mr Asia Inquiry] chaired by Justice Donald Stewart, another giant in the war against organized crime and corruption. Cedric again played the role of the éminence grise to that inquiry. In the result, every principal member of the Mr Asia gang was brought to justice for their murderous rampage up and down the east coast of Australia and internationally. The report on the Mr Asia Syndicate led, inter alia, to the creation of the National Crime Authority [now the Australian Crime Commission] and to the establishment of the office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions. While we now watch with fascination the Underbelly series on television, Cedric lived the Underbelly experience.

During both the Williams and the Stewart Royal Commissions, Cedric would frequently seek the advice of his brother Lester, then a senior officer in the Bureau of Customs, about how to handle the public sector. Lester invariably came through with a way to thread the labyrinthine processes of the bureaucracy.

Cedric was involved with numerous other important public inquiries including the Fitzgerald Inquiry, the Barrier Reef Inquiry into Oil Drilling, the Northern Territory Land Tenures Inquiry, the Royal Commission into the Nugan Hand Group, etc, and several public inquiries conducted by the Criminal Justice Commission.

Cedric represented Australia at the 1988 United Nations Conference on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.

For his contribution to the Williams and Stewart Royal Commissions, Cedric was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia.

Cedric’s contribution beyond the law

A keen Rugby footballer in his younger days, Cedric continued his interest in sport both as a spectator and as Chairman of the Advisory Committee to the Sporting Wheelies and Disabled Sport and Recreation Association (1990-96).

A former Rhodes Scholar, he took on the presidency of the Queensland Rhodes Scholars’ Association from 1996.

Cedric was a member of the RAAF Reserve rising to the rank of Wing Commander, was appointed as a Judge Advocate, and as Honorary ADC to the Queen from 1976 to 1978.

The business world has also benefited from Cedric’s wisdom and commercial insight, as a director of two listed public companies – Consolidated Rutile Ltd and Cudgen RZ Ltd.

Cedric was very active in the affairs of the Catholic Church.

In 1987 he became the first Head of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem as Queensland Lieutenant and Knight Commander. He was also a Knight of the Order of St Lazarus of Jerusalem.

On behalf of Catharina and the Hampson family, I acknowledge with gratitude the presence of numerous members of the Equestrian Order.

In 2012, Pope Benedict XVI awarded Cedric a Knighthood of the Order of St Gregory the Great.

The Private Cedric

Cedric was a true renaissance man.

Cedric has published six works – Shifting Shadows, Cat’s Eye, Truth in Masquerade, Occasions of Sin, Sicilian Vespers, Betty’s Oxford Short Story and Other Tales, and the Brothers Keid.

Cedric was an accomplished painter of landscapes, portraits and religious scenes.

Cedric was a classical scholar without peer in his generation, and had an encyclopedic knowledge of, and appreciation for, classical music.

Like his father Cecil before him, Cedric was interested in bird breeding and kept an aviary at Ascot housing finches and quails.

A communication from His Excellency, the Governor of Queensland

The Chief Executive of the Bar Association, Robyn Martin circulated the following communication yesterday from His Excellency The Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Governor of Queensland:

“As a Life Member of the Association, and for all reasons, the Governor wishes members to know that he deeply regrets his inability to attend the Requiem Mass for our late colleague Cedric Hampson QC. The reason is the Governor is to preside at that time at a meeting of the Executive Council. The Governor respectfully acknowledges the immense contribution of our late colleague to the law and the administration of the law within our State, and conveys his and Kaye’s deepest sympathies to the family.”

To Cedric’s Family

To Cedric’s siblings, immediate family, and extended family, may I observe that the presence of such a large cross section of the Brisbane, Queensland and Australian communities at this service does great honour the memory of your brother, husband, father, father-in-law and grandfather.

Cedric will be a significant figure in the history of Queensland for many generations to come.

Our thoughts, prayers and condolences are with you today and always.

Farewell

Farewell Cedric,

You have fought the good fight, you have finished the race, you have kept the faith.

Mark Le Grand

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white — then melts for ever;

Or like the borealis race,

That lift ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm…

Tam O’ Shanter,

Robert Burns, 1790

Lamble v Howl at the Moon

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. As is the way of barristers, I had planned for this speech on alcohol-related litigation to be a collection of personal war stories in which I made frequent references to my own forensic triumphs, however distant or tenuous they be. I still have some ambitions in that regard but, unfortunately, I need first to deal with a very recent and spectacular loss in the Court of Appeal.

The case concerned licensed premises at Broadbeach called Howl at the Moon where a patron sustained serious injury when he was struck — outside the premises — by a barman, and the issue became whether or not the proprietors were vicariously liable for the employee’s criminal conduct.

The story is probably best begun in 1949, with a barmaid called Mrs Barlowe and a High Court case that many of you will remember called Deatons v Flew (1949) 79 CLR 370. The Plaintiff was a patron who either made an inoffensive remark, or questioned the barmaid’s “chastity and parentage”, depending on who you believe. In any case, Mrs Barlowe assaulted the Plaintiff by throwing some beer over him and then throwing an entire glass at him, so that he lost sight in one eye.

The Plaintiff alleged that the Hotel was vicariously liable for the barmaid’s assault but the High Court held there that she was actuated by malice or other personal motives unrelated to her duties, and that claim failed.

The issue of vicarious liability was considered in some detail by the High Court in Lepore v State of New South Wales & Anor (2003) 213 CLR 511. You may recall that this litigation was concerned with the circumstances in which a school should be liable for sexual misdemeanours carried out by its teachers. The dicta of Gummow and Hayne JJ summarised Dixon J’s judgment in Deatons v Flew as follows:

“There are two elements revealed by what his Honour said that are important for present purposes. First, vicarious liability may exist if the wrongful act is done in intended pursuit of the employer’s interests or in intended performance of the contract of employment. Secondly, vicarious liability may be imposed where the wrongful act is done in ostensible pursuit of the employer’s business or in the apparent execution of authority which the employer holds out the employee as having. … What unites those elements is the identification of what the employee is actually employed to do or is held out by the employer as being employed to do. It is the identification of what the employee was actually employed to do and held out as being employed to do that is central to any inquiry about course of employment. Sometimes light may be shed on the central question by looking at a subsidiary question of who stood to benefit from the employee’s conduct. But that inquiry must not be permitted to divert attention from the more basic question we have identified. …”

That explanation of principle is, of course, closely aligned with the orthodox statement that where an employee carries out an authorised act in an unauthorised way, the employer will be liable, but not otherwise. Later illustrations are to be found in Gordon v Tamworth Jockey Club [2003] NSWCA 82 where a Plaintiff failed to establish vicarious liability against an employer after a drunken cleaner inexplicably attacked her and Blake v JR Perry Nominees [2012] VCA 122, where a Plaintiff similarly failed after he was injured by a co-worker in horse-play: see also Orcher v Bowcliffe [2013] NSWCA 478. On the other hand, there are many cases — particularly involving security guards — where a worker has gratuitously harmed a patron but, nevertheless, the employer has been found liable because it was related to their actual duties: eg Ryan v Anne Street Holdings [2006] 2 Qd R 486, a case concerning the Beat Nightclub in the Valley.

Which brings us to Lamble v Howl at the Moon [2014] QCA 74. It’s a bar at Broadbeach which is run by an Italian family and mostly caters for a tame crowd: over 30’s, mainly women, who are happy to listen to covers on a piano (by “easy listening” artists, I gathered, like Billy Joel or Don McLean).

Those of you who work for Hotels may have noticed that there is something of a pattern in the litigation. November brings Melbourne Cup lunches and claims by female Plaintiffs. December brings all—you—can-drink Christmas parties for tradesmen and then claims by male plaintiffs.

On 8 December 2006, Mr Lamble and a group of work mates from Currumbin Roof Trusses attended Howl at the Moon for their end of year Christmas party. Late in the night, one of Mr Lamble’s work mates was acting in a threatening manner. He was bundled through some glass doors and restrained by four security guards with some limited assistance from the Hotel proprietors. The rest of his work mates could clearly see the robust manner in which he was being restrained and there was some dissent. One of the proprietors, a Mario Zulli, returned and escorted at least one of the workers to the exit. On any view, there followed something of a fracas between Mr Zulli, on the one hand, and a number of the tradesmen in the mall outside the premises.

In the meantime, a barman at the Club called Anthony had been despatched to clean up some broken glass at the entrance to the premises. He attended with a dust bin on a long handle, together with a dust brush. His evidence was that he looked from the entrance out to the fracas taking place in the mall. He noticed that his uncle, Mr Zulli, was being set upon by other people and he went to his assistance. Mr Lamble, at least at this point, was not involved in the fray. He was standing to one side and, it seems, looking elsewhere. The barman, however, approached him and swung the dustpan at his head so that Mr Lamble fell to the ground, and suffered significant head injuries.

The barman subsequently pleaded guilty to a charge of assault occasioning bodily harm. Mr Lamble, however, did not bring any civil proceedings against the barman but only against Howl at the Moon. He contended that the bar was negligent in failing to properly supervise the barman or, alternatively, it was vicariously liable for his conduct.

The first claim was dismissed by the Trial Judge, Justice Douglas. He held that the barman had been specifically instructed to leave security to the bouncers, and that, in any case, given his impulsive reaction to what he saw, it was unlikely that any lack of direction would have been causally related to the incident.

The first claim was dismissed by the Trial Judge, Justice Douglas. He held that the barman had been specifically instructed to leave security to the bouncers, and that, in any case, given his impulsive reaction to what he saw, it was unlikely that any lack of direction would have been causally related to the incident.

His Honour found, however, that the Hotel was vicariously liable for the conduct of the barman. That determination involved a detailed consideration of the law concerning vicarious liability.

In that regard, the key issue became whether or not the conduct of the barman in assaulting Mr Lamble was sufficiently connected to his employment. The Defendant had the benefit of certain factual matters namely:

(a) The barman had the conventional duties that go with that position of serving drinks, cutting fruit etc;

(b) A number of bar staff as well as a security guard gave uncontested evidence that bar staff had never been involved in crowd control;

(c) The assault occurred outside the Defendant’s premises;

(d) The assault was, of course, an illegal act;

(e) The barman said that he acted impulsively to assist his uncle;

(f) An independent witness gave evidence that the barman’s attack on the Plaintiff appeared to be senseless, disproportionate and unprovoked, at a time when the Plaintiff was not involved in any way in the fracas occurring outside.

As noted earlier, the Trial Judge found that there had been an express direction from the bar proprietors to the barman and to other staff that they were not to become involved in crowd control issues but, rather, was to seek out security.

In the event, and notwithstanding those arguments, the employer was found liable, and that finding was upheld on appeal. In particular, the Court of Appeal found that:

(a) Whilst there was a direction to the barman that he should not engage in security, it was not clear that the direction applied to all circumstances. The Court found that, whereas here, the security guards were occupied elsewhere, in detaining the other rogue tradesmen, the barman was acting in the course of his employment in assisting the bar proprietors.

(b) Since the effect of his conduct was to rescue another staff member and to stop a fight which must have been bad for goodwill, the conduct was in furtherance of the Defendant’s interests.

(c) In circumstances where the bar created the environment for the dispute, by selling alcohol late at night, and the fracas involved patrons recently ejected from the bar, the conduct of the barman was sufficiently connected to his employment.

Queensland Bars and Hotels should take note that they may well be found liable for assaults by their staff on patrons on the basis that the acts come within the scope of their employment, even if they have specifically excluded crowd control from their duties. Indeed, it seems that, even if the conduct is misdirected, it may be enough that one of the effects (as opposed to purposes) of the conduct was to benefit the employer.

That is a matter of some moment. Insurers will generally prefer to cover Hotels and Clubs for which there are security subcontractors. The intention, of course, is to use the independent contractors to quarantine the insurer from the vexed issues concerning crowd control (as was done successfully in Orcher’s case). Given the decision in Howl at the Moon, that may not be a sufficient safeguard. There would need to be a direction that employees not involve themselves in crowd control in any circumstances — that is, even in an emergency – and there should be such numbers of security guards that there is never an occasion where the staff need to intervene.

As noted earlier, there are any number of cases in which Hotels have been found liable for violence committed against a patron. Those cases differ from Howl at the Moon in that, for them, the perpetrator was usually a security guard engaged by the Hotel, so that it might properly be said that crowd control was part of the perpetrator’s employment. Obviously, where the security guard is an independent contractor, there can be no vicarious liability.

Patrons suing Hotels; the different classes

It seems to me that Howl at the Moon falls within one class of cases in which a Hotel might be sued by a patron. If we call that first class Harm Caused by Hotel Staff or Security then a second might be Negligence by a Hotel in Supplying Alcohol. A third might be Negligence by the Hotel in Failing to Supervise Conduct between Patrons. And a fourth might be Occupier’s Liability.

Some Practical and Introductory Remarks

Can I say as a practical issue in all of these classes that it will be relevant to ascertain the extent to which the Plaintiff was affected by alcohol at the relevant time?

You will be aware that sections 46 to 49 of the Civil Liability Act 2003 deal with alcohol and its relationship to negligence claims. Section 46 provides in effect that no greater standard of care is owed because a person may be intoxicated. Section 47 relevantly provides that there will be a presumption of contributory negligence on the part of a Plaintiff if the Plaintiff is intoxicated at the time an alleged breach of duty occurred of at least 25%. There are at least four points that should be made about those provisions.

The first is that section 46 does not apply to licensed premises: that is, conceivably, a higher duty of care might be expected if you appreciate that people are habitually drinking there. The second is that the better view is that the presumption will not work against a Plaintiff who is injured by an intentional tort. That is because the relevant provisions of the Civil Liability Act 2003 deal with breaches of duty, rather than intentional torts: Corliss v Gibbings-Johns [2010] QCA 233. The third point to make is that the definition of “intoxicated” in the Civil Liability Act 2003 is that a person is “under the influence of alcohol or a drug to the extent that the person’s capacity to exercise proper care and skill is impaired” so that a defence lawyer will need to ask the Court to draw an inference from peoples’ observations or to obtain a blood alcohol reading. The second possibility is obviously much less subjective but it is difficult to come across. The fourth point is that the statutory presumption sits alongside, of course, the common law doctrine of contributory negligence.

I would add, incidentally, that the law stipulates that the standard of care for contributory negligence is not to be modified on account of drunkenness. One well appreciates that, where you are dealing with certain characteristics such as youth, the duty might be assessed by that cohort: See McHale v Watson (1964) 111 CLR 184. If, however, you slide down a bannister or ride freestyle on a car roof, you cannot contend that it was normal for your state of intoxication: see French v QBE [2011] QSC 105 at [175].

I would also add that, having regard to rule 150 of the UCPR, you are likely to be prevented from running a contributory negligence argument if it has not been specifically pleaded.

I was recently engaged for a Council being sued by a pedestrian. The pedestrian, on his own version of events, had 10 to 20 XXXX Gold pots and walked home before slipping on steps to a Council underpass. There were some vague allegations that the stairway was in bad condition but the story seemed rather implausible, particularly where it involved binge drinking on mid-strength beer, and walking home in the rain wearing thongs manufactured by R M Williams.

I had my instructing solicitor brief a pathologist, a Dr Hoskins, to provide a report on whether or not the Claimant was intoxicated. When the report came back, it was in two sections. The first section looked much like my childrens’ homework. It took into account a number of variables and then calculated that, if a man weighing X kilograms drank Y beers over Z hours, he would have a certain BAC. It was clear that the extent of any intoxication would depend on the final state of the evidence.

The second section of the report was much more exciting. The doctor said, in effect, that whilst he had been asked to speculate on a range of possibilities, he no longer saw the need. When he looked at the hospital records provided, there were some pathology results obtained immediately after the Plaintiff’s admission. The doctor explained that, translated for lay people, they show that the Plaintiff had a BAC of .17 at the time of the accident! I received the report under cover of a rather gleeful email from my instructing solicitor. It read:

“Hi Damien.

Suspect this is what you were after … I believe the layman’s interpretation of Dr Hoskin’s findings is that the Plaintiff was ‘pissed as a fart’. Also acceptable is ‘two sheets to the wind’, ‘blind’, ‘legless’, ‘gone’, ‘FUBAR’ or ‘munted’.”

The claim did not proceed further.

In short, it should be appreciated that establishing that the Plaintiff is intoxicated has at least two useful purposes. The first is that it invokes the statutory presumption for contributory negligence. The second perhaps is that the Plaintiff’s version of events becomes far more tenuous if it can be established that he or she was in no state to act prudently or remember what happened.

I would add that, where you have a Plaintiff who alleges negligence arising out of a Hotel incident, special scrutiny of a quantum claim will often be rewarding. I ran a trial for the Beetle Bar near Petrie Terrace called O’Connell v First Class Security [2012] QCD 100. The Plaintiff was a backpacker from Liverpool. He had been behaving badly and two police officers were called to the premises. They held the Plaintiff but it was the bouncer’s impression that the Plaintiff was about to wrestle free. The bouncer — who was a Maori and also a rugby player — executed a glorious covering tackle which, unfortunately, broke the Plaintiff’s femur. We resisted the claim on liability and quantum but we were unsuccessful on the first ground, particularly in circumstances where the two police officers were not prepared to concede that they were having trouble with the Plaintiff. The medical records from England, however, disclosed that the Plaintiff had a longstanding problem with alcohol and other drugs. Against that background, he was awarded only $8,600.00 for general damages and $6,000.00 for past and future economic loss!

Negligent Supply of Alcohol

Negligent Supply of Alcohol

I spoke earlier about a class of cases where a Hotel might be sued for supplying alcohol to a person until they become drunk. I should say that such a cause of action will be very hard to sustain on the current state of the law.

The high point, in Queensland at least, was a case called Johns v Cosgrove [2000] QCA 157. At first instance, Justice Derrington found the Chevron Hotel at Surfers Paradise liable. The Hotel was of course situated between two major arterial roads. The Hotel staff were aware that the Plaintiff was in the habit of attending the Hotel, drinking heavily and then walking home through traffic. When he was run over on the subject occasion, Justice Derrington found that the Plaintiff was 45% liable, the motorist 30% liable and the Hotel 25% liable. Interestingly, the decision was set aside on appeal but only because it emerged that the Plaintiff had paid a certain witness to give evidence. It is a particularly useful authority for those who find, shortly after a trial, that the Plaintiff has been fraudulent.

In Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club (2003-2004) 217 CLR 469, the High Court was concerned with a claim by a lady who had attended a football function. I should say that I was attending a lunch recently when a mate said to me that he intended “to get drunk, not rugby league drunk, but pretty drunk”. Mrs Cole adopted a similar approach. She started drinking at 9.30 am. The Club seems to have sold her a bottle of spumante at 12.30pm (which she was seen to drink from the bottle and on her own). She was “absolutely drunk” by 1.45pm. She was refused alcohol at 3.00pm and she had become so obnoxious at 6pm that she was asked to leave. She was offered safe transport home in the Club’s courtesy bus but she declined in rather blunt crude terms. As she walked home at 6.20pm, however, with a BAC of .238, she was hit by a car and badly injured.

Mrs Cole sued both the motorist and the Club, and was successful against each with a finding of contributory negligence (30%; 30%; 40%). The Club appealed and was successful. Mrs Cole then appealed further to the High Court. For her it was contended that the Club should have declined to allow Mrs Cole to leave or should have compelled her to travel home safely, or it should have ceased serving her alcohol. The High Court might easily have decided the matter on the relatively narrow basis that any duty of care had been discharged when the Club offered Mrs Cole a lift home. Alternatively, it might have found that the causal link between the negligence and the loss was severed because it could not be shown that any steps taken by the Club would have prevented the accident. Whilst Gummow and Hayne found for the Club on the latter basis, they cast real doubt on the existence of the duty and Gleeson CJ and Callinan J found that, in all but exceptional cases (eg, the patron is too drunk to make a rational choice), a Club or Hotel does not owe a duty of care to Plaintiffs to protect them from intoxication and its possible consequences.

There is a more difficult manifestation of the issue in the case of Scott v C.A.L. No. 14 Pty Ltd [2009] TASSC 94. That was a Lord Campbell’s Action. The deceased had arrived at the Defendant Hotel in a “funk”. He had provided the Hotel with the keys to his motor bike and he had proceeded to get very drunk (he was later found to have a reading of .253). As the night wore on, the Publican offered to arrange for the deceased’s wife to collect him but he responded by saying “If I want you to call my wife, I’d fucken ask ya”. The deceased later asked for the keys to his motor bike and they were duly given to him by the Publican. He fishtailed down the driveway, drove 7 kilometres and then died in a crash. Blow J dismissed the claim on the basis that there was no relevant duty of care. On appeal, the Chief Justice indicated that he preferred the view of Gleeson CJ and Callinan J in Cole (to the effect that no relevant duty existed), and he found squarely that there was no duty on a pub to withhold the keys. It should be said that the balance of the Court allowed the widow’s appeal. They found that a duty of care was owed and that the Hotel did not take sufficient steps to discharge it.

The matter came before the High Court in C.A.L. No. 14 v Scott (2009) 239 CLR 390. The claim was dismissed and the headnote records the ratio of Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ:

“Outside exceptional circumstances, the proprietor and licensee of licensed premises, while bound by important statutory duties in relation to the service of alcohol and the conduct of premises in which it is served, owe no general duty of care at common law to customers which requires them to monitor and minimise the service of alcohol or to protect customers from the consequences of alcohol they choose to consume.”

The upshot is that it is now very clear that, in the absence of very special circumstances, a Hotel proprietor has no duty to protect patrons from intoxication and its consequences. A finding in the patron’s favour will be more likely where he is incapable of making a rational decision or where the pub has some control over the means of departure.

Attacks by One Patron on Another

Attacks by One Patron on Another

As mentioned earlier, a third class of cases will be those where one patron harms another.

In Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre v Anzil (2000) 205 CLR 254), where the Plaintiff was attacked and injured while making his way through an outdoor car park in a shopping centre, the claim failed because it was held that the occupier could have no control over the criminal conduct of a third party. It was noted in Chordas v Bryant (Wellington) (1988) FCA 462, however, that a Hotel could be liable for an attack by one patron upon another if the first patron was known to be difficult or aggressive when intoxicated. A similar result was reached more recently in Spedding v Nobles [2007] NSWCA 29. That was because Hotels are considered to exercise real control over their patrons.

For those decisions where one patron has been assaulted by another, it will be relevant to consider whether the Hotel had knowingly or recklessly supplied the intoxicated patron with alcohol beyond a responsible point or otherwise failed to remove a threat. Livermore v Crombie [2006] QCA 169, for instance, is a case concerning the Eimeo Hotel in Mackay. Two brothers became embroiled in an argument with a patron because they considered he had looked at one of their partners. The incident was defused and the Hotel continued to serve the two brothers. About 30 minutes later, one of the brothers king-hit the Plaintiff and he was badly injured. He sued the Hotel alleging that it should have evicted the brothers after the verbal argument. The Trial Judge held rather robustly:

“Common sense suggests that if every patron of a hotel who exchanged a cross word with another patron over some perceived slight was ejected on the off chance that they might later launch an unprovoked and unexpected attack upon somebody entirely different, many such establishments would be largely empty.”

An appeal was dismissed because the members — led by Keane JA — held that reasonable care did not require at the earlier point that the brothers be ejected.

In Adeels Palace Pty Ltd v Moubarak [2009] NSWCA 29, a New Year’s Eve function was being held at a reception centre in Punchbowl. I asked my wife – who is Lebanese – to read the judgment and she noted that the function was unusual in that (although it was not the subject of judicial comment) she could see from the names that it was attended by both Muslims and Christians. In any case, there was a physical altercation over a girl called Leila and the assailants then left the function centre before returning to shoot the Plaintiff. He contended that the Hotel was negligent in failing to arrange sufficient numbers of security staff.  On the basis of Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre v Anzil, the Palace contended that it did not owe a duty of care to prevent the criminal conduct of others and submitted that no exception should be made for licensed premises, particularly he was not intoxicated.

The Court held a duty could be owed by a Hotel in the circumstances. In short, the Trial Judge held that Adeels Palace owed a duty of care to patrons at the New Year’s Eve function to take reasonable care to guard against injury from other patrons (whether the conduct of the latter was criminal or not). The Trial Judge found that the security arrangements were inadequate and materially contributed to the injuries.

One might wonder if an unarmed security guard might have prevented injuries by firearms and the Appellant raised that argument in the Court of Appeal. That Court held, however, that the Trial Judge was entitled to find that the use of force against the security staff was quite unlikely.

When the matter went to the High Court, it affirmed the principle that Adeels Palace owed a duty of care to prevent injury to patrons from violent, quarrelsome or disorderly conduct. In the event, however, the decision was overturned (that is, the claim failed) on the basis that it could not be shown that the presence of a security guard at the door of the restaurant or on the floor of the restaurant, would necessarily have deterred the assailant. See also Cregan Hotel Management v Hadaway [2011] NSWCA 338, Portelli v Tabriska Pty Ltd [2009] NSWCA 17 at [60] and Rooty Hill RSL v Karimi [2009] NSWCA 2 at [33] — [35]. In Portelli, in particular, the President of the Court of Appeal doubted a finding of the primary Judge that the duty of care to protect against the criminal conduct of patrons could not extend to the public street. See also Day v Ocean Beach Hotel [2013] NSWCA 250.

In Orcher v Bowcliff (supra) at first instance, the Trial Judge found that, when a glassie crossed the road to strike another person in a gratuitous attack, the actions were borne of some unknown and unexplained personal animosity with no relevance to Mr Paseka’s employment or his employer’s interest so that a claim based on vicarious liability failed. The Judge found, however, that a security guard employed by an independent contractor, Mr Paya, should have intervened in the “developing situation” across the road and the Hotel was found liable. The Court of Appeal in Orcher’s case accepted that the Hotel by its staff owed a duty of care to prevent harm to patrons of the Hotel but it found that the assault occurred without warning so that, considering a possible breach prospectively rather than retrospectively, it could not be concluded that the security company was liable. The Hotel succeeded on the further basis that the security guard was not employed by it.