Marshall Cooke RFD QC

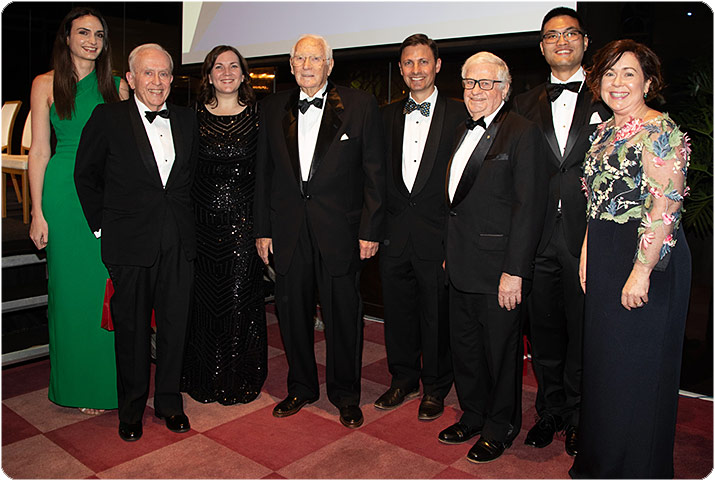

Presented by Justin Byrne

Nelson “Marshall” Cooke, known to most simply as “Marshall”, was admitted as a barrister in 1962 — the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis and also the year of the tragic death of film icon Marilyn Monroe. Closer to home in 1962 the Honourable Sir Own Dixon sat as Chief Justice, Robert Menzies was Prime Minister and Rod Laver won the French, Australian and US Open Titles and Margaret Court, not to be outdone repeated those same feats, French, Australian and US Opens.

Remarkably that was some 57 years ago now, the year when Marshall Cooke first graced the Queensland Bar with his eloquent nature.

Marshall has, over time, developed something of a multi-practice in the areas of Constitutional and Administrative, Property, Planning and Environment, Commercial, and Criminal Law and Marshall was appointed Silk in 1980.

He was also an Officer in the Royal Australian Navy and retired having attained the Rank of Commander and obtained the honour of receiving the Reserve Forces Decoration for his service. He has appeared in many military tribunals (including courts-martial) and inquiries, and whilst serving was in fact appointed as both a Defence Force Magistrate and also as Judge-Advocate in the Australian Navy.

In the mid to late 1960’s Marshall was elected and served as Councillor with the Pine Rivers Shire Council and was then subsequently elected Federal Member of Australian Parliament (Petrie) in 1972, and thereafter, sat as a Member of Joint Committee on Self-Government for the Australian Capital Territory.

Amongst Marshall’s many other achievements are being appointed Commissioner to inquire into financial and electoral corruption in Queensland Trade Unions in the late 1980’s and then Chief Commissioner appointed to inquire into the Privatisation and Sale of Papua New Guinea Banking Corporation in 2002.

Marshall has also held many other professional positions over the years including:

- Was Chairman of Queensland Barristers’ Admission Board

- He served 2 terms on the Bar Association Committee

- Was Member of the University of Queensland Law Faculty Board

- Acted as Counsel for PNG Government at Sandline (Mercenaries) Inquiry

- Had several Constitutional References in the PNG Supreme Court including the reinstatement of a Government Minister and also the Manus Island Detention Centre matter.

Amongst Marshall’s many hobbies and interests, he has in a former life represented Queensland in a winning Debating team when he was at the University of Queensland, and also found time to represent Queensland as a water polo player in the National Championship.

He was the Treasurer and later Chaired the Queensland Swimming Association not long after coming to the Bar, and notably, for his long association with Queensland Water Polo, he was duly awarded a Life membership of the Queensland Water Polo Association.

Marshall has had a long and distinguished career at the Bar. He has seen many aspiring young barristers come and go in that time, and has seen many changes in how we perform our roles from an administrative perspective. Life may well appear to have become somewhat complicated at times in that respect, but the reality is that whether it be 1962 or present day, 2019, the barrister’s role still requires the same certain attributes including:

- Capacity to think on one’s feet and respond to changing situations;

- Ability to think strategically;

- Always remain calm under pressure (or at least not show your panic);

- Speak well and hopefully enjoy public speaking.

These are things that Marshall Cooke has now done well for more than half a century, truly remarkable!

Can you all please join me in recognising Marshall Cooke for his outstanding contribution to the Queensland Bar and the fact that he survived more than 50 years in that regard!

John Gallagher QC

Presented by Sophie Gibson

There is a simply stated theme in John’s time at the Bar, the message is that real friendship is precious and that the bedrock of friendship is loyalty. It is a short credo, but it takes a deal of discipline to act by it.

No biography of John, no matter how brief, could be complete, without mentioning that his nickname is well known as “the Crocodile” or to those affectionate to him, “the Croc”. It is said that he will bite and not bark.

John, also known as “Gall”, was admitted to the Bar in March 1964. Gall did not start in an elite building. He first practised from rooms that were dubbed “Outs of Court”, before he was then able to purchase a room that became available in the actual Inns of Court, but the reality was that the junior Bar was only a group of about 50 barristers at that time, most of whom had served in the second world war, in different theaters.

Junior members would regularly gather together in the common room of the Inns of Court for luncheon provided by Bruno and his wife. Judges would regularly join these lunches on a Friday. Every barrister was very welcome to attend and to sit and discuss the gossip and news of the day. It was a very collegiate place.

The old Supreme Court building burnt down in 1968. When the new courthouse was built it had the then very modern feature of air conditioning. Fees were calculated as a fee on brief with subsequent “refreshers”. Time charging did not exist.

John found that appearing with great Silks was a tremendous learning experience. He appeared with some greats, including Gerard Brennan QC, Cedric Hampson QC and Dan Casey. He remembers Cedric Hampson QC, not just as being the finest practitioner of his era, but as also being a great leader and a great man.

John suffered a deep sadness in the very sudden and unexpected death of his first wife, Wendy, at a time when they had four young children. He remembers and cherishes the friendship of many colleagues who took care of him at that time. One of these was Cedric, another was Ian Callinan, both of whom showed him true friendship by their conduct.

Cedric gave John an instruction about a principle of legal practice. It was that one should never start a fight, but that if someone started a fight with you, you had to finish it. While John adhered rigidly to that principle it is fair to say that he actually did not need any instruction from Cedric about it. He has never thought the Bar is a place for the faint hearted and he believes in fearless advocacy. He also believes that no one should expect a prize for working hard or being intelligent. These are “givens”, as he says.

After many years at the Bar it is friendship and character that remain as the only important values to him. He has seen many great barristers and Judges come and go but good friendships have endured. As John became more senior and took Silk a new chapter of his life at the Bar opened up. I am told that one characteristic of the later years of his career was his encouragement of younger barristers. He saw that encouragement as a natural and enjoyable responsibility of a senior barrister, and as the way the Bar is meant to work.

John eschews the practice of barristers telling war stories that only reflect well upon themselves. It is boring for one thing, and also leaves out the other half of reality, which can be amusing and instructive, namely the stories where things do not go well for us. One of the features of being a friend of John’s is enjoying his great sense of humour, self-deprecating remarks, and his philosophical insights, often delivered with the witty turn of phrase of a keen observer of human nature.

And despite his many happy years at the Bar, John has never been so happy as he is now in retirement, enjoying the love and company of his delightful wife Susan.

Please join with me on congratulating John Gallagher on more than 50 years as a practicing barrister.

Lister Harrison QC

Presented by Rachel Taylor

Lister was born on the 1st December 1944. The youngest of four children, his father had been at the Bar and then went on to become a lecturer in law at the University of Queensland. His mother had lectured there too, in the English Department.

Lister’s mother died in 1945, and his father then died in 1966, which in fact led to him marrying Gailene later that same year, rather earlier he says than would otherwise have happened, since he states that in those days it would have been scandalous for them to live together whilst unmarried.

Lister and Gailene went on to have three children and six grandchildren, all of whom still live in relatively close proximity to their parents. Lister himself attended Church of England Grammar School (now called the Anglican Church Grammar School) Brisbane. Between 1967 and 1968, Lister was Mr Justice Gibb’s associate. He followed his Honour Justice Gibbs from the Federal Court of Bankruptcy sitting in Sydney and Melbourne, to the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory sitting, of course, in Canberra.

Whilst living in Sydney, Lister was able to take advantage of his dual residence to “straddle the dingo fence”, and get admitted in both Queensland and New South Wales. However, when Lister’s associateship finished and upon his return to Brisbane, he then developed a practice principally in crash and bash and legal aid maintenance.

Also, by the time of his return to the Queensland Bar, Lister had noticed that the Barristers seemed to make real money from trials and barristers had a disinterest (at least at that time) in writing opinions. So, he duly adopted the strategy of producing a satisfactorily profitable opinion practice. In 1983, he took Silk.

After a few years at level 17, of the then MLC, Lister set up chambers by himself on level 12 of that same building. When the accountant occupying the space next to him was sent to jail for tax fraud, and that space became vacant, Lister was approached by the now Australian High Commissioner to the UK and former Senator and Attorney General, George Brandis, amongst others, to establish a new group on that floor. These are the chambers that have continued in one form or another to become today’s Gibbs Chambers at No 95 North Quay. David Russell QC, a long-time member of that group and devoted fan of Lister’s, apologises for not being with Lister to celebrate tonight.

Lister’s practice at the Bar has taken him on many travels, including to Johannesburg — for the South African rebel cricket tour, in breach of anti-apartheid sanctions. In the inevitable litigation that followed, when the then Foreign Minister, Bill Hayden, refused Lister’s clients’ visas to come to Australia, Lister and the other lawyers (who included Stephen Charles QC and Peter Heerey of Melbourne) had to travel to Johannesburg to take instructions.

Again, although Lister was briefed extensively for one particular developer involved in the home unit litigation that fed the Bar in the earlier part of the 1980s, much to his consternation he had to return the brief for that client in order to fulfil a promise to Gailene’s mother to take her and the family on a Pacific cruise. But by doing that he avoided the indignity of having to tug the forelock to the representatives of a foreign power when that client’s litigation ultimately ended up before the Privy Council.

However, his attitude to the Crown is now somewhat similar to his attitude to his appendix, that is if it’s not playing up, then best leave it alone. Lister was offered a Centenary Medal in 2001 for “services to the law”, but politely declined the offer.

Lister’s wife tells us that he comes from a long line of spendthrifts to the extent that, for example, in Aesop’s fable of the ant and the grasshopper, he has always sided with the grasshopper. Nevertheless, he advises that he has promised faithfully that once he has paid his current tax bill, he will definitely start saving for his future retirement.

And perhaps consistently with his hopefully new-found frugality, tonight he is wearing a dinner jacket that his father had made for him by Christison and Burnett, High Class Tailors, of the Commercial Union Building, Eagle Street, the typed label in the inside pocket of which bears the date March 1963.

Please join me in congratulating Lister Harrison on his outstanding service as a barrister of more than 50 years standing.

Ian Hanger AM QC

Presented by San-Joe Tan

Ian was called to the Bar in December 1968.

It was an interesting bunch: Lister Harrison QC, Angus Innes, Justice Richard Chesterman, Justice Bob Douglas, Bob Hall, Judge Gary Forneau, Kevin Martin and Judge Philip Nase.

Ian spent 1969 and 1970 in London attending operas, plays, ballets and concerts, working in Lavender Hill, serving in the Royal Green Jacket Regiment and making the acquaintance of a certain Mr McKenzie — whom the world thinks — he befriended. He would deny that, but it resulted in a certain famous case.

After returning overland to Australia — doing some devilling in Hong Kong on the way — his first case was a dividing fences matter. Totally bamboozled by a subject that they didn’t teach in law school, he consulted his master soon to be Justice Bill Pincus — then a successful junior. Bill’s sound advice was that there was actually an Act of parliament called the Dividing Fences Act and perhaps it would be a good idea to start there. Ian did just that.

In those days he cut his teeth with Justices Fryberg, Chesterman, Harrison, and Spender valiantly fighting about $500 claims. Together, and headed by George Fryberg; Richard and Ian began Moore Chambers in the then Ansett Centre.

Subsequently they moved to the level 17 of the MLC Building with Harrison, Pincus, Thomas, Glen Williams, Richard and David Cooper, and David Robin, Jeff Spender and Brian O’Donnell

In 1976, Ian had the privilege of going to the Privy Council as junior to Bruce McPherson and appearing against John Macrossan leading Bill Carter leading Jonathan Sumption. Sometime thereafter, his wife tried to persuade him whilst they were in London, to look up his old client Mr McKenzie whom he had made famous but he didn’t seem inclined to do so.

In the seventies, he accepted and enjoyed doing a great deal of private prosecution work in the District Court and, as a prosecutor, referred in glowing terms to Jack Kimmins DCJ.

Ian enjoyed being in a number of matters with the Solicitor General for Australia Sir Maurice Byers and in that role worked with Bill Gummow and Bob French, both of whom of course went on to became Justices of the High Court. When Mabo was just a letter before action, Sir Maurice, Bob French and Ian spent a full week in conference discussing land rights cases in order to advise the then Commonwealth Attorney General.

Ian was also involved with Bill Pincus in advising on liability in the Agent Orange litigation and in respect of the Commonwealth’s liability arising out of the Maralinga Atomic bomb tests.

In one matter, Warman v Dwyer, he was soundly thrashed by Danny Gore in the High Court and his wife says she is still traumatised about it. This may account for any odd conduct you might have seen throughout the last 20 years.

In 1988 he was Chair of the Committee of Inquiry into the Industrial Relations System in Queensland and his report was praised by both unions and employers. He was senior counsel assisting both the Parliamentary Judges Commission of Inquiry and the Inquiry into the Criminal Justice Commission. As if those inquiries were not enough, he was the commissioner for the Royal Commission into the Home Insulation Program.

He has been an adjunct professor at the University of Queensland and has been made a permanent honorary professor at Bond University.

In 1990 he began mediating — 2,000 mediations later is where he is today. To be fair he is something of an expert, having led workshops in London, Edinburgh and Hong Kong and given talks in many other countries too. As recently as this month he was invited to give a paper at the Malaysian ADR conference. He is a mediator for the Court of Arbitration for Sport and an arbitrator for the Chinese International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission and is conducting an arbitration in Beijing in November.

At the end of last year Griffith University conferred on him an Honorary Doctorate. He has not retired, and we are reliably informed that his wife won’t let him. She often reminds him of Bert Klug’s wise advice “Life is like riding a bicycle. If you stop pedalling, you will fall off”.

Please join with me in congratulating Ian Hanger on more than 50 years as a barrister in Queensland.

Many excellent articles and presentations have been written or given touching upon Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562. The attention so given is entirely appropriate. The decision, especially Lord Atkin’s judgment, has been cited on countless occasions and has had a profound influence on Anglo-Australian law. But it is also worthwhile to spare a moment to reflect on a decision cited by the House of Lords in Donoghue v Stevenson, and the Judge behind that decision. The decision was MacPherson v Buick Motor Co, 217 NY 382, 111 NE 1050 (NY 1916), and the Judge behind it was Justice Benjamin N Cardozo.

In MacPherson v Buick Motor Co, it was held by the influential New York Court of Appeals in 1916 that a manufacturer of an automobile owed a duty of care in tort to a consumer injured whilst driving the vehicle, notwithstanding the absence of privity of contract.

First, a little about the man, Benjamin Cardozo.

Life and career of Cardozo J

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo, of Sephardic Jewish/Spanish-Portuguese heritage, was born in New York City on 24 May 1870 to Rebecca Nathan and Albert Cardozo. He had a twin sister, and they had four other siblings. His grandfather had been nominated a Justice of the New York Supreme Court, but died before he took office. Benjamin Cardozo’s own father was in fact a New York Supreme Court Justice, but he resigned amidst a judicial corruption scandal. This had a profound effect on Benjamin, who was determined to restore his family’s name.

Benjamin’s mother died in 1879, when he was still quite young.

At age 15, Cardozo attended Columbia College, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree followed by a Master’s in Political Science. Then, in 1889, he attended Columbia Law School. He was by all accounts a brilliant student. After two years there, he passed the New York Bar exam in 1891 and began practising law in New York City alongside his brother. He remained in practice with Simpson, Warren and Cardozo until 1913. He gained an esteemed reputation in commercial law.

In 1913, having practised for about 23 years, Cardozo was elected to a 14 year term on the New York Supreme Court, due to start on 1 January 1914. But in February 1914, he was appointed as a temporary Judge on the New York Court of Appeals, the State’s highest court. In 1917, Cardozo J became a permanent member of the Court of Appeals. In 1926, he was elected to a 14 year term as Chief Judge of that Court.

After having served 18 years on the Court of Appeals, Cardozo CJ resigned in 1932 to take up an appointment as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Even though he was a Democrat, he was appointed by the Republican President, Herbert Hoover. His appointment was met with universal acclaim. The Senate confirmed his appointment by a unanimous vote.

Cardozo J was on the US Supreme Court for six years, supporting a number of Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives, as a member of the so-called “Three Musketeers” along with Justices Brandeis and Stone.

He suffered a heart attack in 1937 and a stroke in 1938. He passed away, aged 68, on 9 July 1938, in Port Chester, Rye, New York State.

He had never married. He was a modest man of high principles, loved by his colleagues.

In addition to his many influential judicial decisions, he was a prolific extra-judicial writer. Amongst other works, he is particularly renowned for his work “Nature of the Judicial Process” (1921), designed for judges but which is standard reading for American law students.

MacPherson v Buick Motor Co

Donald MacPherson’s 1911 Buick collapsed on the road to Saratoga Springs when he was driving just 8 miles per hour. He was thrown out and injured. One of the wheels contained defective wood, and the spokes had “crumbled into fragments”. Mr MacPherson had bought the Buick from a retailer. The retailer had bought the car from Buick Motor Co. Buick Motor Co was the manufacturer of the vehicle, though it had purchased the wheel as a component part from Imperial Wheel Co of Michigan. There was evidence that the defect could have been discovered by Buick Motor Co had it carried out a reasonable inspection. The Supreme Court held that Buick Motor Co was liable in negligence to Mr MacPherson, which decision was upheld by the Supreme Court Appellate Division. By majority, the Court of Appeals held that the decision of the Appellate Division should be affirmed.

Previously, it had been the rule in New York, based on the English decision of Winterbottom v Wright (1842) 10 M & W, 152 ER 402, that a manufacturer’s liability for negligence only extended to purchasers with whom they were in privity of contract. That English case concerned a horse drawn carriage. The New York cases recognised an exception to that rule, where the product was “inherently dangerous”, the leading example of which was a case concerning poison which had been wrongly labelled as dandelion extract: Thomas v Winchester, 6 NY 397 (NY 1852). But as the trial judge had summed up to the jury in MacPherson v Buick, “an automobile is not an inherently dangerous vehicle”. The then Chief Judge also noted in dissent that an automobile moving at only 8 miles an hour “was not any more dangerous to the occupants of the car than a similarly defective wheel would be to the occupants of a carriage drawn by a horse at the same speed”.

In MacPherson v Buick, however, Cardozo J, in delivering the leading judgment, closely analysed the cases said to be authority for the exception, pointing out the inconsistencies and uncertainties to which the exception gave rise, and the illogicality of the distinction between products inherently dangerous and those which were dangerous because of negligent construction. He also referred to the need of the law to keep a-pace with developing technology. He considered that what those earlier cases in fact decided needed to be re-visited. He said:

“The question to be determined is whether the defendant owed a duty of care and vigilance to any one but the immediate purchaser… We hold, then, that the principle of Thomas v Winchester is not limited to poisons, explosives, and things of like nature, to things which in their normal operation are implements of destruction. If the nature of a thing is such that it is reasonably certain to place life and limb in peril when negligently made, it is then a thing of danger. Its nature gives warning of the consequences to be expected. If to the element of danger there is added knowledge that the thing will be used without new tests, then, irrespective of contract, the manufacturer of this thing of danger is under a duty to make it carefully. That is as far as we are required to go for the decision of this case. There must be knowledge of a danger, not merely possible, but probable… There must also be knowledge that in the usual course of events the danger will be shared by others than the buyer… If he is negligent, where danger is foreseen, a liability will follow.”

His Honour found those factual matters to be made out in that case. Cardozo J observed, “The dealer was indeed the one person of whom it might be said with some approach to certainty that, by him the car would not be used.” He noted more generally that “it is possible that even knowledge of the danger and of the use will not always be enough. The proximity or remoteness of the relation is a factor to be considered.” But proximity or remoteness were not a problem in the instant case when the above mentioned factors were present.

These pronouncements do not seem all that remarkable to the modern day Anglo-Australian lawyer.

Donoghue v Stevenson

It is not surprising that MacPherson v Buick should have been referred to, and cited by, the House of Lords. MacPherson v Buick was the first common law case dealing with the product liability owed to a consumer by a manufacturer of mass produced products and upholding a duty of care in negligence.

Lord Atkin had this to say (at pages 598-9):

“It is always a satisfaction to an English lawyer to be able to test his application of fundamental principles of the common law by the development of the same doctrines by the lawyers of the Courts of the United States. In that country I find that the law appears to be well established in the sense in which I have indicated. The mouse had emerged from the ginger-beer bottle in the United States before it appeared in Scotland, but there it brought a liability upon the manufacturer. I must not in this long judgment do more than refer to the illuminating judgment of Cardozo J in MacPherson v Buick Motor Co in the New York Court of Appeals, in which he states the principles of the law as I should desire to state them, and reviews the authorities in other States than his own. Whether the principle he affirms would apply to the particular facts of that case in this country would be a question for consideration if the case arose. It might be that the course of business, by giving opportunities of examination to the immediate purchaser or otherwise, prevented the relation between manufacturer and the user of the car being so close as to create a duty. But the American decision would undoubtedly lead to a decision in favour of the pursuer in the present case.”

This was high praise indeed.

The qualification by Lord Atkin in the penultimate sentences in that paragraph was unnecessary, because Cardozo J indicated at several points in his judgment, that the principle would not apply if there was, and was known to be, a reasonable opportunity for intermediate examination or examination before use.

Lord Atkin then continued to state the principle as it applied to English and Scots law (at page 599):

“… a manufacturer of products, which he sells in such a form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care”.

This was masterful in its reduction of the principle to one sentence.

Even if Lord Atkin only “drew support for his own approach” [1] from MacPherson v Buick, the latter decision still had an influence on the result as is evident from Lord Atkin’s glowing praise.

Of course, there is much more to Lord Atkin’s speech than a statement of and upholding of the principle of a manufacturer’s product liability to a consumer. It has been pointed out there are similarities between Lord Atkin’s neighbour principle and the judgment of Cardozo CJ in the case of Palsgraf v Long Island Railway Co, 248 NY 339 (1928). [2] But it is unlikely Lord Atkin was aware of that case, as Palsgraf was evidently not cited in argument, and it is not referred to in any of the judgments, in Donoghue v Stevenson.

Moving on to other Law Lords, the above passage from Cardozo J’s judgment was set out by Lord MacMillan (one of the other majority Judges in Donoghue v Stevenson) at [1932] AC 562, 617-8. That also speaks volumes.

Lord Buckmaster, in dissent in Donoghue v Stevenson, distinguished MacPherson v Buick on the basis that it was a decision that “a motor-car might reasonably be regarded as a dangerous article”: [1932] AC 562, 577. Lords Atkin and MacMillan did not agree with that interpretation of MacPherson v Buick, with Lord Atkin referring (as had Cardozo J) to the illogicality of the distinction between a thing dangerous in itself, and a thing which becomes dangerous by negligent construction (see pages 595-6 of [1932] AC). The fact that Lord Buckmaster felt the need to distinguish a decision from another jurisdiction is testament to the force of its reasoning.

Whether Cardozo J expanded the exception in Thomas v Winchester or laid down a new principle altogether does not matter. They are one and the same thing as a matter of practice. Cardozo J so expanded the “exception” to the point where the privity rule, if not “cut out and extirpated altogether”, was “left with the shadow of continued life, but sterilized, truncated, impotent for harm”: Nature of the Judicial Process, pp98-9.

Cardozo J’s legacy

What is remarkable about MacPherson v Buick Motor Co is not only the significance of what it decided, and the fact that it was the first case to so decide. It is also the fact that it was decided in 1916 barely two years after Cardozo J’s appointment to the Court of Appeals, whilst he was still a temporary judge, and the fact that it was a majority decision, in which Cardozo J’s judgment was given notwithstanding the strong dissent of the then Chief Judge, Willard Bartlett.

Indeed, Cardozo J’s boldness and eloquent writing style are amongst the reasons why Cardozo J/CJ’s judgments have had such a profound effect, not only in the United States but also elsewhere.

MacPherson v Buick is not the only occasion where the judgments of Cardozo J/CJ are cited by Anglo-Australian courts. An austlii search of “Cardozo” in the High Court of Australia directory alone produced a staggering 100 results, including his decisions from a wide range of contexts, as well as his extra-judicial writings.

A few of the more well known examples however are:

-

Wood v Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon , 222 N.Y. 88; 118 N.E. 214 (N.Y. 1917) (“The law has outgrown its primitive stage of formalism when the precise word was the sovereign talisman, and every slip was fatal. It takes a broader view to-day. A promise may be lacking, and yet the whole writing may be ‘instinct with an obligation,’ imperfectly expressed. If that is so, there is a contract”);

- Loucks v Standard Oil, 120 NE 198, 201 (NY 1918) (“The courts are not free to refuse to enforce a foreign right at the pleasure of the judges, to suit the individual notion of expediency or fairness. They do not close their doors, unless help would violate some fundamental principle of justice, some prevalent conception of good morals, some deep-rooted tradition of the common weal”);

- Beatty v Guggenheim, 225 NY 380 (NY 1919) (“A constructive trust is the formula through which the conscience of equity finds expression. When property has been acquired in such circumstances that the holder of the legal title may not in good conscience retain the beneficial interest, equity converts him into a trustee”);

- Wagner v International Ry Co, 133 NE 437 (NY 1921) (“Danger invites rescue”);

- Meinhard v Salmon, 249 NY 458, 164 NE 545 (NY 1928) (“A trustee is held to something stricter than the morals of the market place. Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive, is then the standard of behaviour … the level of conduct for fiduciaries [has] been kept at a higher level than that trodden by the crowd”);

- Ultramares Corp v Touche, 174 NE 441 (NY 1932) (no duty of care where it would lead to “a liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class”);

- Baldwin v GAF Selig Inc, 294 US 511 (1935) (“The Constitution was framed under the dominion of a political philosophy less parochial in range. It was framed upon the theory that the peoples of the several states must sink or swim together, and that in the long run prosperity and salvation are in union and not division”);

- Palko v Connecticut, 302 US 319 (1937) (freedom of speech is “the matrix, the indispensable condition, of nearly every other form of freedom”).

As Lord Atkin shows us all by his example, we should not be reluctant to look to American authorities where relevant. There are many instances where Anglo-Australian law has been influenced by American law, and there is no reason why this should not continue to be so. This is not only at the common law level, but also at the statutory (including constitutional) level. For example, it is not widely known that the Judicature Acts 1873-1875 were influenced by the “Field” Code of Civil Procedure (NY) of 1848, which abolished the forms of action as well as the procedural distinction between suits in equity and actions at law. That followed upon the abolition of the Court of Chancery as a separate court in New York State in 1846. The Field Code preceded the Common Law Procedure Act of 1852.

The above is not to say that cross fertilisation is a one way street. Nor is it to say that we should always reach the same conclusions. But the way American lawyers have grappled with similar problems means that their jurisprudence has been and can continue to be of assistance in resolving disputes according to our own standards. As Cardozo J himself observed in Loucks v Standard Oil, 120 NE 198, 201 (NY 1918), “We are not so provincial as to say that every solution of a problem is wrong because we deal with it otherwise at home”.

Dr Stephen Lee, Barrister

[1] Chapman, The Snail and the Ginger Beer: The singular case of Donoghue v Stevenson, Wildy, Simmonds & Hill, 2010, p42.

[2] Knapp, International Encyclopaedia of Comparative Law (Martinus Nijhoff 1983), p71.

Author: Harry Ognall

Publisher: William Collins

Reviewer: DW Marks QC

Sir Harry was born in 1934 in Lancashire. He read law at Lincoln College, Oxford, starting in 1953. After study abroad and serving as Marshall to Pearson J, he joined chambers in Leeds, practising on the common law side.

This brief memoir (147 pp) is valuable for Sir Harry’s account of his days at the Bar, the greater part of the book. While time has moved on, and some fashions and opinions have doubtless shifted, this account of the arc – from pupil to High Court Justice in England — is topical and engaging. It is in turn serious and humorous.

Several trials are recalled in pithy sketches.

The two trials that made the greatest impression upon me were those of Mr Peter Sutcliffe (aka “The Yorkshire Ripper”) where Sir Harry appeared for the prosecution and of the “Zimbabwe Air Force Six”, where Sir Harry appeared for the defence. Both were demanding and challenging trials.

In the former case, the then Attorney-General, Sir Michael Havers, had decided to lead the prosecution. Sir Michael submitted to Boreham J, at a directions hearing, that in light of the unanimous psychiatric opinion, the prosecution was minded to dispose of the case by way of pleas of guilty to manslaughter, not murder.

Boreham J indicated that he was not prepared to accept the pleas. This dealt Sir Michael out of testing the psychiatric evidence at the later trial. Thus, Sir Michael cross-examined Peter Sutcliffe and Sir Harry had the important task of crossâexamining the psychiatrists.

His account of how he planned that cross-examination, and conducted it, is an object lesson in testing expert evidence.

The trial in Zimbabwe posed other difficulties and challenges.

First, the death penalty was on the table. Secondly, in accordance with Zimbabwean procedure, the confessions of the accused had been confirmed by them before a magistrate.

The threats and beatings, and the systematic way in which prison accommodation had been repeatedly switched so as to deprive the accused of any access to legal counsel, was not before the magistrate, when the confessions were confirmed. This was critical to the defence.

Again, cross-examination of a key witness would be crucial. And so it proved. The men were acquitted by a court presided over by a judge, with two assessors.

Sir Harry’s asides through his memoir are serious, and humorous, by turn. His criticism of the course of the police investigation in Sutcliffe demonstrates (as if it were needed) the danger of targeting (or closing one’s mind to other possibilities). Lives were lost as a result of single minded pursuit of a particular case theory. Sir Harry attributes the fact that Sutcliffe was at liberty to commit at least 13 murders and 7 attempted murders to “a combination of luck and prolonged investigative incompetence”. This is not to say that all involved were incompetent but, from this account, there was enough incompetence to go around.

On the lighter side, from his days as a junior, Sir Harry recalls sitting in a magistrate’s court, waiting for his case to be called, when a self-represented defendant was strongly advised by the chairman to seek legal representation:

-“I don’t want it. The Good Lord will take care of me.”

-“The Bench thinks that you would be well advised to have the services of someone who is better known locally.”

Sir Harry speaks less of his time on the Bench, naturally.

But his account of the adjectival facets of life as a High Court Justice in London, and on circuit, is of interest.

There are a few specific cases noted. I was challenged by his account of the trial of Dr Cox, on a charge of attempted murder connected with the death of a patient. This seemed to have been euthanasia, at the urging of some loved ones concerned at the continued suffering of the patient.

And he gives an account of his treatment by the press, on discharging an accused, Mr Colin Stagg, who had been charged with murder based on a remark in extensive pretext calls from a police officer. It seems that no apology was forthcoming from the Press when, years later, forensic evidence and a confession established that the murderer was someone altogether different.

The attention from the Press was highly focused and lengthy, at the time of the discharge of Mr Stagg, but nonâexistent when the true murderer was exposed.

He also expresses concern about the ability of an accused to defend a case brought many years after an alleged event (p 141). While not minimising the nature of the crimes that might be charged, Sir Harry gives trenchant reasons for caution in this difficult area.

Sir Harry’s memoir accompanied me in recent travels and provided much needed diversion. Sir Harry writes well: pointedly, briefly, and persuasively.

“A Life of Crime – the Memoirs of a High Court Judge” by Harry Ognall, now published in paperback by William Collins, 2017, ISBN 978-0-00-826748-3

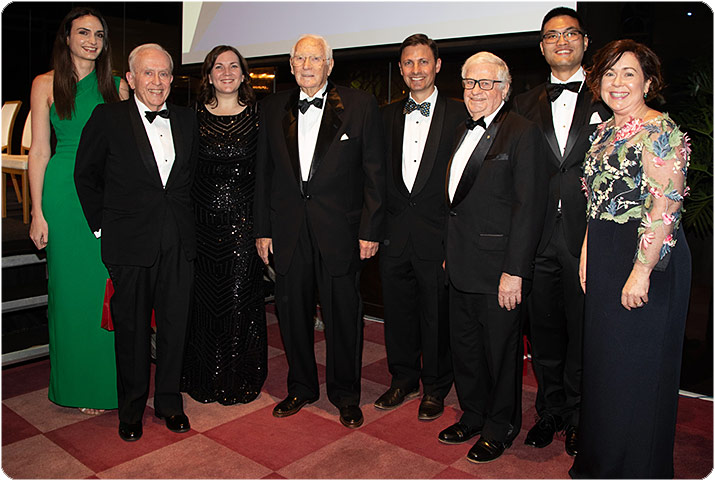

Several members of the Queensland Bar recently attended the Australian Bar Association’s international conference in Singapore on 11 and 12 July.

The program consisted of both plenary sessions and smaller streams exploring a diverse range of issues from consideration of the need for an international commercial court for Australia to cross-border insolvency and third-party litigation funding.

The conference was opened by a joint address by the Honourable Chief Justice Kiefel AC of the High Court of Australia and the Honourable Chief Justice Menon of the Supreme Court of Singapore. Their Honours spoke about the common legal heritage of Australia and Singapore as well as the developing institutional bonds between the courts and legal professions of both countries. Engagement by the Bar as a whole with the broader profession and in the region was a focus of the conference. Sessions including a panel of senior in-house counsel, issues in international arbitration and the report prepared by the Honourable Roger Gyles AO QC on opportunities for Australian barristers in international arbitration. There was a strong feeling among presenters that Australian counsel were under-represented in international arbitration work compared to other overseas lawyers, and particularly members of the London bar.

Practical skills and practice development were also covered across the conference, including sessions on ‘the seven deadly sins of oral advocacy’, digital practice management and expert evidence. Junior members of the bar were particularly appreciative of the opportunity to sit down with senior counsel from around the country at a ‘meet the silks’ session.

Contributions by Queenslanders to the program were well received, with presentations by Peter Dunning QC (anti-suit injunctions), Cate Heyworth-Smith QC (a comparative discussion of ethics in advocacy) and Kathryn McMillan QC (expert evidence – 21st century challenges).

Convergence 2019 concluded with a black tie dinner (with big band) at the magnificent Clifford Pier, capping off a lively program of social events which also included arrival rooftop drinks and a welcome event at the National Gallery of Singapore.

Conference chair Dominique Hogan-Doran SC and her team deserve congratulations for putting together an engaging and comprehensive program. From Singapore, the ABA National Conference returns home, being co-hosted by the Queensland Bar in combination with our annual conference.

Save the date: 2020 BAQ ABA Conference, 5-7 March 2020, W Hotel Brisbane

Jules Moxon, Barrister

Author: Michael Evan Gold

Publisher: Cornell University Press 2018

Reviewer: Dr. Louise Floyd

Ever tried explaining to a young law student how to spot an issue in a problem scenario? Or have you tied yourself in knots trying to explain subjective and objective standards?

These crucial matters, so important to developing an understanding of the law and how to use it, are discussed in a very useful publication by respected Cornell University academic, Professor Michael Evan Gold in his new work: A Primer on Legal Reasoning (Cornell University Press 2018).

This excellent American publication describes itself as being aimed at pre-law and early law students (Introduction at 2). However, I would venture to suggest that anyone wanting a refresher in legal reasoning would find a place for this book on their bookshelf.

The chapters traverse topics such as: Issues (Chapter 1); Identifying the Governing Rule of Law (Chapter 2); Arguments in General (Chapter 6); Arguments Classified by Function (Chapter 7); Arguments Based on Evidence (Chapter 8); Policy Arguments (Chapter 9); Interpreting Statutes (Chapter 16); and Application of Law to Facts (Chapter 18).

Given that most Australian law schools have been instructed by the Committee of Australian Law Deans to re-emphasise some of the fundamentals, such as statutory interpretation, these topics are extremely important.

The book is particularly noteworthy given its US origin. Many US Law Schools use the Socratic or questioning teaching method. This book challenges that approach and underscores the importance of arming all law students with fundamental skills — which we go on to develop and use throughout our legal careers.

Professor Gold is a well-respected member of staff at Cornell. Professor Gold’s US perspective for skills that are universal in the western world of law is enriching for us all.

The inaugural Indigenous Law Student Program commenced on 8 April 2019 with the successful student, Ms Charlotte Batterham, attending the first component of a three tiered internship scheme. The Program is designed as an introduction to life at the Bar, encompassing three weeks experience with the Courts and in Barristers’ chambers. A joint initiative of the Bar Association of Queensland in partnership with the Queensland and Federal Courts, the program provides an innovative and solid foundation to support Indigenous law students with the intention to increase the number of Indigenous Barristers at the Queensland Bar.

Ms Batterham spent her first week at the Federal Court under the guiding hand of the Honourable Justice Collier. An intensive schedule included an introduction to the Registry of the Federal Court and the Federal Circuit Court with case managers, involvement with the Federal Court Native Title team and time spent in Court with Justice Collier and Justice Jarrett. The program, structured by the Court, included an in-depth examination of how a case progresses through the Court systemÂâfrom new online e-lodgement to final judgement.

At the Supreme Court, Charlotte’s second week involved attending Court every day, including observing applications, a civil trial and a criminal trial. Each day the immersive experience concluded in a debrief with the Honourable Justice Phillipides, who provided context and insight into the day’s proceedings.

Ms Batterham described the program as an invaluable experience:

“It is often said, we don’t know what we don’t know until we know it, and how true it is after experiencing a week of seeing our Courts in action. Seeing behind the scenes of the Federal Court and the Supreme Court, along with attending Court, bought together all of the pieces of knowledge learnt while undertaking my law degree.”

The final component of the program, a week in Barristers’ chambers, will take place in the university break in September. The program aims to bring the theoretical learning of study to the real world, crossing a range of legal areas, dependent on the candidate’s interests. Access to the legal system, accompanied with the opportunity to meet and experience the everyday routine of Barristers and the Judiciary, provides the opportunity to break down barriers for Indigenous law students who may be considering life at the Bar.

Ms Batterham encourages other Indigenous law students to apply for the program. “I am grateful I had support to gently nudge me to apply for the opportunity,” she said.

“The Judges and their associates are impressive people, dedicated, genuine and supportive. As Mark Twain says ‘It is noble to teach oneself, but still nobler to teach others’.”

Application for the 2020 Indigenous Law Student Program close on 30 September 2019.

The Association would like to express its thanks to Justice Collier and Justice Philippides for their Honours’ contribution and assistance in making the program such a success.

Nadine Davidson-Wall

Recently, we were fortunate to have psychologist, Hanne Paust, speak to members about resilience at the Bar. The seminar focussed on what resilience means in the context of being a barrister and how we can all improve it.

For those members who did not attend the seminar, either in person or online, it is available for viewing via the Bar Association’s CPD online library. The time invested in viewing this presentation will be rewarded with relevant knowledge that may have long-term benefits to your wellbeing and practice. I recommend it to all members.

Resilience was defined in the seminar as “the ability to respond positively to adversity.” One might think of resilience, in this regard, as a set of skills that is to be developed each day (on a continuing basis). By using the right tools, and being aware of the relevant triggers, we can develop the skills to improve how we respond to adversity on the job.

The BarCare Committee is focussed on and committed to assisting members of the Bar Association in improving their resilience. In this regard, BarCare has a number of initiatives targeted to achieving this goal, which include offering regular CPD sessions on mental health and wellbeing to members.

One of the lesser-known initiatives of BarCare offers direct access to psychologists, for any member who may need such assistance. Each Bar Association member is entitled to avail themselves of 3 consultations each year at no cost with any one of the psychologists included on the Association’s panel.

The service is entirely confidential. You will not speak with anyone from the Bar Association to organise your appointment. You simply contact the relevant psychologist directly, informing them that you are a member of the Bar Association. They will invoice the Bar Association directly, without referring to you at all, and the Bar Association will cover the cost of 3 consultations in any given year.

It is a service that could significantly improve the wellbeing of any member who feels they may need some assistance. Details of the panel of psychologists and how to utilise this service can be found on the BarCare page, which is available on the Bar Association’s website once you have logged on to your member homepage.

Finally, BarCare is also presently in the process of putting together an online “hub”, which is intended to be a comprehensive resource for Bar Association members on matters concerning mental health and wellbeing. More information about the BarCare Hub will be available to members in the near future.

12 December 2018

I wanted to start by dealing with the elephant in the room: it’s been said that, as a group, and as individuals, the new silks aren’t very diverse. Can I say – we resemble that remark? If we were a suburb of Brisbane, we’d be Camp Hill: modestly charming, a little bit vanilla and, amongst our number, one super industrious Greek.

I would, however, make special mention of Lincoln Crowley. He’s not only a new silk. He’s the first indigenous QC that Queensland has ever produced. I would also say on behalf of all the new silks that we are very conscious that the law is at its strongest and most credible when it’s informed by people from every walk of life. We intend to take up the Chief Justice’s challenge this morning and to make sure that, through our work with community organisations, with juniors or with clients, all the different voices are heard.

It seems very strange to be talking about what we would, or could, do as senior counsel when, only a few weeks ago, we were not at all sure that we would make it. The law is so binary in lots of ways, win/lose, get paid/ don’t get paid, but never more so than when you’re opening that letter from the President of the Bar, Rebecca Treston. You don’t know if it’s going to be a snake or a ladder, but you know it’s going to be a very long one. You steel yourself for rejection and then, at the very last moment, you deploy your emotional air bags like some 15-year-old kid, telling yourself, “I know I’m not going to get it and that’s absolutely fine by me”.

Mostly, we’re just grateful to be here.

Which leads me to the theme of my talk. I have approached the new intake about a topic that we might address. We agreed that what we’d really like to do is to acknowledge a huge debt to the older members of the Bar, for the assistance they have given us to date in our careers – teaching us court craft, involving us in strategy and, most of all, showing us what a strong work ethic looks like. As it happens, I had asked the staff at the Bar Association where to pitch this talk. They told me that it would be a good idea to be deferential without being sycophantic, and I thought this theme might be right in the sweet spot…

I approached the new silks for some specific examples of assistance received, but they weren’t very helpful. No one wanted to bell the cat. Andreatidis told me about a time after a big trial where he flew back to Brisbane with his leader, Roger Traves, and they walked over to the airport car park together. Nick reckons he lost his car and then he lost his silk. So he ended up spending an hour driving around the enormous car park with his head out the window of his Mini Cooper, yelling out “Travesy, Travesy!”. I don’t want to make light of how harrowing that must have been for both Nick and Roger, but it didn’t seem especially instructive for the rest of us …

Lincoln told me a story about when he was a reader in Sydney, and he asked a silk what he needed to do to be the best barrister ever. The silk told him, “Mate, it’s all about return sales. It’s like you’re running a shop selling lemon slices. And there’s a whole row of shops all selling lemon slices. You just need to make sure you’re selling the best lemon slices”. That advice seemed kind of Sydney-centric, and a little unhelpful for your Queensland audience. So, I’ve decided I’d best draw on my own experiences with senior counsel.

First, I want to give an example of how silks can put you at ease. I had only been admitted a few years, when I was briefed in a murder trial. It was making me seriously anxious. I was thinking that I hadn’t yet acquired the skills for that level of contest, and I was right. But this old criminal barrister took me aside at the Criterion Tavern. He said, Damo, you know what a murder trial is? It’s an assault trial with one less witness. That was, strangely, rather comforting.

Second, silks can help you avoid hubris. Years later, I was a junior to a fashionable commercial silk. And we were on Day 2 of the trial (so my leader was just starting to grasp all the facts), when he said to me, I’d like you to cross-examine the next witness. I was really chuffed, thinking that he must have spotted something special in my intellect. No. He said to me, “I really want to signal to the judge how desperately unimportant this next witness is, and letting you cross-examine is just the ticket”. He later told me Bill Pincus had said exactly the same thing to him, so I should be chuffed.

Third, silks can help you see the positives. I was working in chambers late on a Saturday night. I think I was trying to understand the rule in Barnes v Addy. I wouldn’t want his Honour Justice Jackson over there to think I wasn’t enjoying myself. I was. But I couldn’t help wondering if my wife and my friends over at the Lychee Lounge in West End weren’t better placed for fun. Anyway, at about 11pm, I make my way to the carpark. And there’s a silk there, and he’s had a big night out with his son at the casino. Which makes me even crankier, thinking I must be the biggest sad sack in Brisbane when even old silks are having a better time. But I talk to him and I grumble that I’ve been working. He says to me, how lucky are you? How’s that, I ask? He says, “Your practice must be really busy that you have to work on a Saturday night!” I walked away with my head held high.

Fourth, silks can keep you grounded. I was working as Counsel Assisting to Geoff Davies on the Patel Inquiry which was set in Bundaberg. The report was coming together rather well, and I bounded into Geoff’s office to tell him, excitedly, about an idea I had for the cover. I said, let’s have an image of a ute that’s taking a winding road that goes through a sugar cane paddock. It communicates FNQ, Focus, Energy and Optimism. Geoff just pointed at the door without looking up, and said: “We will never speak of this again”. He went with a plain purple cover…

The scariest advice I have received from a silk came only two weeks ago. It was from a Rockstar barrister in Sydney who sent me an email with congratulations which continued:

“Being a silk is quite different from being a junior. Being a silk is also quite different from having silk. The change in status, if you will forgive the pomposity, involves some attitudinal changes, in how you present yourself and in how others see you. If you want to have a chat about it, we’ll be at Sunshine Beach for most of January.”

It’s hard to interpret that email as meaning anything except:

(a) Your personality needs major renovations; and

(b) It can’t wait until February.

I tell myself that you probably all received similar notes when you took silk, but you don’t need to tell me straight away.

I would like to say something on a serious note. Its fashionable nowadays for people to say about lawyers that they don’t produce anything, they don’t do anything useful. I don’t agree. When you listen to public debate today, there is such a clumsiness, a violence, a move to outrage and a disconnect in communication. But what our industry, our profession, teaches us is to discuss issues with civility, to present our thoughts logically, to respect opposing views, to argue with clarity and to bring evidence to bear in order to persuade others to a particular position. Those skills are sorely needed in our community.

I was educated at a Catholic boys’ school in Coorparoo and, if you made bad choices, you had to write out a very long essay by Cardinal Henry Newman called the Definition of a Gentlemen. I keep it close nowadays to remind me how to behave when I’m faced with a particularly obnoxious opponent. I actually posted it to a young woman recently who was being treated very poorly by her partner, just to let her know what she was entitled to expect.

There was one part of the essay which resonates with the point I would make. The writing didn’t need to be gendered but it was, and it described a Gentleman in part as follows:

“… He has his eyes on all his company; he is tender towards the bashful, gentle towards the distant, and merciful towards the absurd; he is seldom prominent in conversation, and never wearisome…

If he engages in controversy of any kind, his disciplined intellect preserves him from the blundering discourtesy of better, perhaps, but less educated minds, who, like blunt weapons, tear and hack instead of cutting clean, who mistake the point in argument, waste their strength on trifles, misconceive their adversary, and leave the question more involved than they find it.”

The Chief Justice spoke glowingly this morning about the privilege of being an advocate and the responsibilities of being a leader. As the newest silks, we approach this appointment, this elevation, with a growing sense of certainty about what is of value, with an excitement about the intellectual opportunities the position offers, and with a sense of wonder and humility about our good fortune in joining this tribe.

Damien Atkinson OAM QC

The following summary notes of recent decisions of the High Court of Australia provide a brief overview of each case. For more detailed information, please consult the Reasons for Judgment which may be downloaded by clicking on the case name.

In this case, the question before the High Court was whether, in circumstances of a unique family structure and an artificially-conceived child, New South Wales legislation could be invoked by s 79(1) Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) to help determine whether the appellant, being the contributor of semen for the purpose of artificial insemination, was a parent for the purposes of Pt VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). Ultimately, the Court found that it could not, and the relevant provisions of the State law were inoperative by operation of s 109 of the Constitution.

Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ

19 June 2019

Background

The appellant and the first respondent were, for many years, close friends. [3]. In 2006, the first respondent, who wanted a child, asked the appellant to provide her with his semen so that she could artificially inseminate herself. [3]. The appellant duly did this, and the first respondent ultimately gave birth to a child. The first respondent and the second respondent, her female partner, have primary care over the child. [3]. However, the appellant is named on the child’s birth certificate as her father, and he has maintained a presence in her life, including by supporting her financially. [3]. In 2015, the first and second respondents decided to move to New Zealand with the child. [4]. The appellant consequently commenced proceedings in the Family Court, seeking, among other things, orders conferring shared parental responsibility and restraining the relocation of the child. [4].

Statutory regime

At the heart of this appeal lay the Commonwealth and New South Wales statutory regimes for determining the parents of children, and the question of whether the New South Wales regime is picked up by s 79(1) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) and applied to applications for parenting orders under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). [1]. The respondents relied upon ss 14(2) and 14(4) of the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW). [1]. These provisions establish an irrebuttable presumption with respect to the use of fertilisation procedures that:

“If a woman (whether married or unmarried) becomes pregnant by means of a fertilisation procedure using any sperm obtained from a man who is not her husband, that man is presumed not to be the father of any child born as a result of the pregnancy.”

Part VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) allows for parenting orders to be made. [5]. Of particular relevance is s 60H, which sets out some presumptions as to the parentage of an artificially-conceived child. [10]. However, under s 69U, these presumptions are “rebuttable by proof on a balance of probabilities”. [14]. The majority found that s 60H does not exhaustively define who can be a parent of an artificially-conceived child. [26]. Ultimately, the question of who is a parent under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) is one “of fact and degree to be determined according to the ordinary, contemporary Australian understanding of ‘parent’ and the relevant circumstances of the case at hand”. [29].

Finally, s 79(1) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) provides:

“The laws of each State or Territory, including the laws relating to procedure, evidence, and the competency of witnesses, shall, except as otherwise provided by the Constitution or the laws of the Commonwealth, be binding on all Courts exercising federal jurisdiction in that State or Territory in all cases to which they are applicable.”

The purpose of s 79(1) is “to fill a gap in the laws which regulate matters coming before courts exercising federal jurisdiction by providing those courts with powers necessary for the hearing and determination of those matters”. [30].

The majority’s consideration

The majority, comprising of Kiefel CJ and Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ, began a discussion of the issues by examining the presumptions created by ss 14(2) and 14(4). [32]. Critically, their Honours found that the presumption those provisions create “are ‘irrebuttable’ rules determinative of a status to which rights and duties are attached”. [34]. Consequently, even though the presumption was not able to be relied upon in criminal prosecutions, it was not “procedural”. [35]. Nor was it in fact rebuttable. [36]—[37]. Thus, ss 14(2) and 14(4) did not constitute “a law relating to evidence or otherwise regulating the exercise of jurisdiction. It is a conditional rule of law determinative of the parental status of the persons to whom it applies which operates independently of anything done by a court or other tribunal”. [39]. Therefore, s 79(1) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) does not pick them up.

While this was enough to dispose of the appeal, the majority also sought to deal with the appellant’s submission that, in any event, s 14(2) cannot be picked up “because the Family Law Act has ‘otherwise provided’.” [40]—[41]. Their Honours described the regime established in Pt VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) as beginning with the plain English meaning of “parent”, but expanding it in certain respects, particularly via s 60H. [44]. Consequently, Pt VII is “complete upon its face” and so is not liable to be picked up by s 79(1). [45]. Further, the “evident purpose” of Pt VII is for the Commonwealth to “have sole control of the provisions that will be determinative of parentage” under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). [48]. Thus, s 79(1) would also be prevented from picking up ss 14(2) and 14(4). [48]. It also follows that there is an inconsistency between Pt VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) and ss 14(2) and 14(4) of the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW). [51]. The majority found that, to the extent of the inconsistency, Pt VII prevails by operation of s 109 of the Constitution. [52]. Thus, “that means that the whole of ss 14(2) and 14(4) are excluded”. [52].

Finally, the majority turned its attention to an alternate argument raised by the first and second respondents: that the ordinary English meaning of “parent” excludes a “sperm donor”. [53]. Their Honours relied on the finding that the interpretation of “parent” relied both upon the understanding of the word “and the relevant facts and circumstances of the case at hand.” [54]. The interpretation proposed by the respondents simply did not accord with the facts as found by the primary judge. [54]. Thus, this argument, too, failed. [55].

Edelman J’s reasons

Although Edelman J agreed with the majority’s orders, his Honour wrote separately to expand upon his Honour’s interpretation of s 79(1) in Rizeq v Western Australia (2017) 262 CLR 1. In his Honour’s view, “laws that confer powers upon a court to make substantive orders in relation to the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of persons” are not “laws that regulate or govern the federal authority to decide”. [60]. Together, ss 14(2) and 14(4) constitute “a rule of substantive law”. [69]. Further, it is “inseparable from the court’s substantive powers to determine and declare who is a parent”. [71]. Regardless of which of these two characterisations is preferred, Edelman J was of the view that it is apparent that s 14(2) “is a law that applies of its own force” and so is not picked up by s 79(1). [72]. While that may be the case, his Honour agreed with the majority’s reasons regarding the inconsistency between ss 14(2) and 14(4) of the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW) and Pt VII of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). [72]. It followed that his Honour agreed with the orders proposed by the majority. [73].

Disposition

In the event, the High Court allowed the appeal. [56], [73].

Northern Territory v Sangare [2019] HCA 25

In this appeal, the High Court unanimously confirmed that the impecuniosity of an unsuccessful party, generally speaking, is not a consideration relevant to the exercise of the discretion to award costs. Accordingly, the Court of Appeal had erred in finding that the impecuniosity of the unsuccessful party, without more, was a sufficient ground upon which to deny the successful party an award of costs.

Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, and Nettle JJ

14 August 2019

The respondent, a citizen of Guinea, had commenced proceedings in the Northern Territory against the appellant seeking damages in the sum of $5 million for defamation. [8]. The respondent alleged that a briefing note, provided by the Chief Executive of the Northern Territory Department of Infrastructure to the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship in relation to the respondent’s application for a temporary work visa, was defamatory of him. [7].

The action was dismissed at first instance and on appeal. The Court of Appeal described the appeal against the decision at first instance as “without merit” and “doomed to fail”. [9]—[10], [16]. Notwithstanding this, the Court of Appeal refused to make the usual order for costs because such an order would (on its view) be futile due to the respondent’s impecuniosity. [20].

The appellant obtained special leave to appeal against the decision of the Court of Appeal on the ground that the discretion of the Court had miscarried in point of principle. [21]. The appellant argued that the impecuniosity of an unsuccessful party was not, without more, sufficient to justify a decision to deny the successful party its costs. [1], [21].

The High Court unanimously allowed the appeal. In a joint judgment their Honours explained that the consideration of the respondent’s impecuniosity was not relevant to the proper exercise of the Court’s discretion as to costs. [36]. Their Honours added that “[w]hether a party is rich or poor has, generally speaking, no relevant connection with the litigation”. [32]. In addition, their Honours held that the Court of Appeal was wrong to consider that such an order would be futile. [34]. It could not be assumed that the creation of a debt by an order was of no benefit to a creditor, or that the respondent would never have the means to pay it in whole or in part. [35].

Glencore International AG v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] HCA 26

This case involved an application by Glencore to restrain the Australian Taxation Office from using documents leaked as part of the “Paradise Papers”. The documents were subject to legal professional privilege. However, the High Court held that legal professional privilege operates only as an immunity (from being required to produce documents in certain circumstances), and was not a right that could found a cause in action (such as to support an injunction, or an order for delivery up of the documents). Further, there was no basis for extending the law to allow the privilege to be used as a right; firstly, because the present state of the law already struck a balance between competing public interests; secondly, because doing so would be inconsistent with how the common law develops — through the application of settled principles to new circumstances, not through abrupt change (as the plaintiffs’ case required).

Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle, Gordon, and Edelman JJ

14 August 2019

Background

The plaintiffs — companies in the Glencore group — sought orders against the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) and its officers, restraining them from making use of certain documents, and for delivery up of those documents (the “Glencore documents”). The Glencore documents had been created for the sole or dominant purpose of providing legal advice by the law firm Appleby. They had been stolen from Appleby’s electronic filing system and provided to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, as part of the so-called “Paradise Papers”. [1]— [2].

It was not in dispute that the Glencore documents were the subject of legal professional privilege. [5]. However, the defendants demurred to the plaintiff’s statement of claim, on the ground that no cause of action was disclosed by which the plaintiffs were entitled to the relief sought. [4]. The plaintiffs’ claim for relief was premised entirely on legal professional privilege. [7]. In substance, the question was whether legal professional privilege provided a right capable of being enforced, or whether it operated only as an immunity from providing documents. [5].

Did legal professional privilege afford a right to obtain relief against the ATO?

The plaintiffs contended that the scope of the privilege should reflect its policy rationale (being to further the administration of justice “through the fostering of trust and candour in the relationship between lawyer and client”). That policy rationale would be advanced through recognition of an actionable right to restrain the use of privileged documents. [10]. They argued that for equity to only provide relief where documents retained their confidential character (as with the equitable duty of confidence), revealed a “gap in the law”. Also, they submitted that decisions in other common law jurisdictions had recognised a right to relief in these circumstances. [11].

The High Court unanimously, in a joint judgment, rejected the plaintiffs’ contentions, and upheld the defendants’ demurrer (that there was no basis for the relief sought). [12]. The key reason for doing so was that the plaintiffs’ arguments assumed that “legal professional privilege is a right capable of being enforced”. Instead, their Honours said that the privilege is “only an immunity from the exercise of powers which would otherwise compel the disclosure of privileged communications”. [12]. Such a characterisation was consistent with the history of how the privilege had developed historically, and was reflected in other decisions of the High Court — most notably in Daniels Corporation (2002) 213 CLR 543, where it was described as being an “important common law immunity” (per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ). [23].

As to whether policy reasons would justify recognition of a right to relief, their Honours said that, in the development of the privilege, courts had “struck a balance” between competing public interests. [29]. It was the “policy of the law that the public administration of justice is sufficiently secured by the grant of the immunity from disclosure”. [32]. Further, the submission that common law courts elsewhere had provided for relief on the basis contended for was “incorrect”. [37]. The English cases referred to were based on the equitable doctrine of confidence, not legal professional privilege. [37]—[39]. Lastly, their Honours said that, for the plaintiffs to succeed, there would have to be the creation of a “new, actionable right respecting privileged documents”. [40]. But this is “not how the common law develops. The law develops by applying settled principles to new circumstances”, and so policy considerations “could not justify an abrupt change”, as sought by the plaintiffs. [40]—[41].

Accordingly, the defendants’ demurrer was upheld, and the plaintiffs’ proceeding was dismissed with costs. [43].

Maneesha Prakash

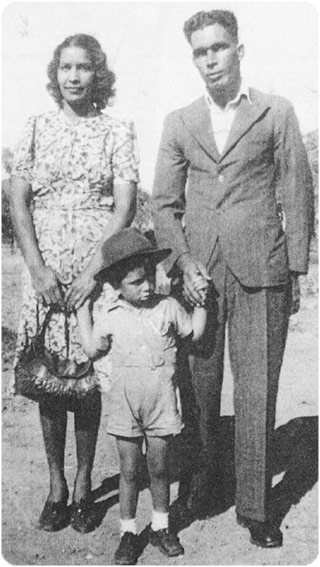

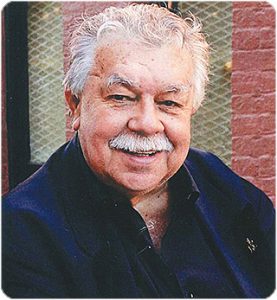

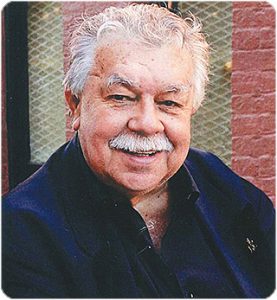

A.K.A. Mullenjaiwakka

6 April 2019 saw the passing of Australia’s first Indigenous barrister, Lloyd Clive McDermott, also known as Mullenjaiwakka. John Fraser wrote this tribute to Mullenjaiwakka after joining family, friends and colleagues at the celebration of Mullenjaiwakka’s life at Randwick Golf Club on 16 April 2019.

Mullenjaiwakka

11 November 1939 — 6 April 2019

It is with great sadness that I write this tribute to the great man, Lloyd McDermott, a.k.a. Mullenjaiwakka, who passed away on 6 April 2019.

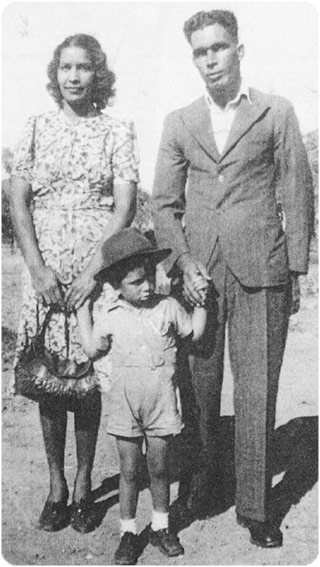

Lloyd was born in Eidsvold in 1939. His father, Clive, worked as a farm labourer. His mother, ‘Aunty Vi’, instilled in Lloyd the need to apply himself.

In 1955 Lloyd’s parents, having saved the necessary money, were able to send Lloyd to Church of England Grammar School (Churchie). It should be noted that Lloyd’s parents were not people of means. Lloyd eventually was awarded an academic scholarship and so was able to finish his schooling at Churchie.

Lloyd was a brilliant sportsman, excelling in all sports, but particularly prominent in Rugby and Athletics. From Churchie, Lloyd went on to study at the University of Queensland. Again, he was prominent in Rugby and was a member of a very successful first-grade team that won a number of premierships. He represented Queensland and, in 1962, was selected to play for the Wallabies against the All Blacks. He was the first Indigenous man to achieve such selection.

In 1963 Lloyd was a certain selection to tour South Africa as a member of the Wallabies. However, Lloyd effectively ruled himself out of selection when he refused to accept “honorary white” status from the South African Government. The man of unfailing principle could not, and would not, accept such a title.

Lloyd later went on to study law and, in 1972, was admitted to practice as a Barrister. Lloyd was Australia’s first Indigenous person to be admitted as a Barrister.

Lloyd worked for a time at the Commonwealth Deputy Crown Solicitor’s office and then, in around 1976, went to the private Bar in Sydney. He practised mainly in criminal law and developed a very busy practice. In recent times, Lloyd was a member of the Mental Health Tribunal of NSW.

In addition to his legal work, Lloyd had a great love of music, reading and travel.

Another one of Lloyd’s great achievements was the establishment of the Lloyd McDermott Development Team, which has helped many young Indigenous men and women play Rugby and Netball. He also had a broader programme of supporting and encouraging young Indigenous persons in their educational pursuits.

Lloyd was a great family man. His two daughters, Phillipa and Judy, are testament to his love and warmth as a father.

I was fortunate enough to attend the Funeral Service for Lloyd on 16 April 2019. It was an inspiring occasion, which lasted about 3 hours and had as its backdrop the beautiful coastline around Malabar (Sydney).

It is very difficult to adequately sum up the life of someone such as Lloyd. He was a trailblazer, in many ways. He was highly successful, but always maintained an air of humility and kindness. His success was even more stunning given the times from which he emerged. As a sidenote, it is remarkable that Lloyd did not start school until he was 11 years old, as Aboriginal children were not allowed to attend school in his town.

Vale Lloyd McDermott, Barrister, activist, sportsman and family man. The world is a sadder place for your departure.

John Fraser, Barrister