Introduction

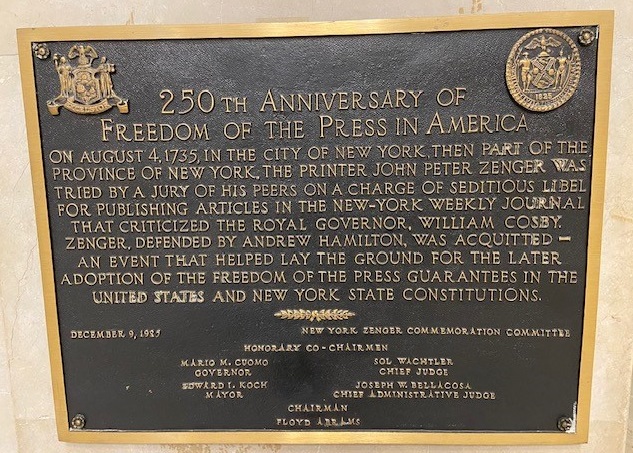

John Peter Zenger was tried for seditious libel in the New York Supreme Court in 1735. He was acquitted by a jury, contrary to the direction of the presiding judge, de Lancey CJ, as to the law. Zenger’s Case was a milestone in the evolution of certain fundamental freedoms in the United States of America, including freedom of the press. This article aims to show why Zenger’s Case is also important to an understanding of freedoms secured by Australian law.

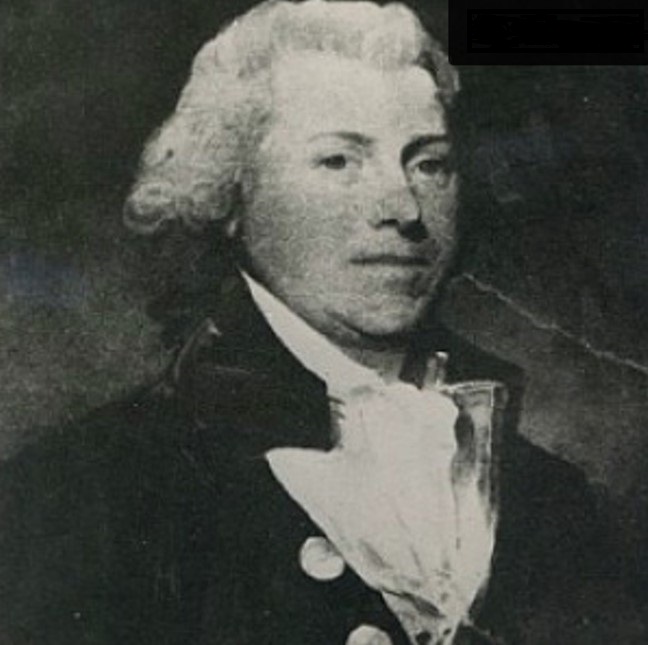

James de Lancey

It is convenient to begin by saying a few words about the presiding Judge, de Lancey CJ.

James de Lancey was born in New York City in 1703.

He came from a wealthy family.

He was educated in England, at Cambridge. He studied law at Inner Temple where he was called to the Bar.

In 1725, he returned to New York to practise law and enter politics.

In 1729, he was appointed to the New York Assembly.

In 1730, he was appointed a justice of the Supreme Court of New York.

In 1733, he was appointed Chief Justice, at the relatively young age of 30. He held that position until 1760. From time to time he served as Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York. In that capacity, in 1754, De Lancey granted the charter (under George II) for the creation of King’s College, now Columbia University.

As Chief Justice, he presided over the trial of John Peter Zenger in the New York Supreme Court in 1735. But there is a back-story.[1]

Cosby v Van Dam

In 1733, de Lancey J sat on a case involving a lawsuit brought by the newly appointed Colonial Governor of New York, William Cosby. Cosby had been appointed many months prior to his arrival in New York from England. Rip Van Dam was acting Governor in his absence. On his arrival in New York, Cosby sued Rip Van Dam, to recover one-half of the salary Van Dam had received in the meantime. Van Dam came from a well respected Dutch family. Cosby was quickly seen by native New Yorkers as an avaristic and nepotistic appointee. Cosby even passed an executive Ordinance specifically to allow him to bring the suit in a Court of Exchequer without a jury. He knew a local jury would rule against him.

Leading New York attorneys James Alexander and William Smith appeared for Van Dam, and argued that the commissions of the judges were invalid for two reasons: first, because they were only during the Crown’s pleasure, and not during good behaviour, and, second, because the Ordinance setting up the Court was made without legislative approval. Justices De Lancey and Frederick Phillipse, having royalist sympathies, rejected those objections and upheld Cosby’s claim. But Chief Justice Lewis Morris gave a strong dissent, which he then had published in pamphlet form.

In his anger, Cosby removed Morris from office, and made James De Lancey Chief Justice in his place.

This created a furore.

The New York Weekly Journal

Up until 1733, the sole newspaper in New York, the New York Gazette, was sympathetic to the government. But German immigrant John Peter Zenger, backed by Morrisite supporters, had lately set up an independent newspaper, the New York Weekly Journal.

Replica of the printing press used by Zenger, on display at Federal Hall, New York.

Zenger published articles critical of the Governor, in his Journal.

For example, it was said:

“The people of this City and Province think as matters now stand, that their liberties and properties are precarious and that slavery is [likely] to be entailed on them and their posterity … I think the Law itself is at an end. We see men’s deeds destroyed, judges arbitrarily displaced, new courts erected, without consent of the Legislature by which it seems to me, trials by juries are taken away when a Governor pleases, men of known estates denied their votes, contrary to the received practice… Who is then in that Province [to] call any thing their own or enjoy any liberty than those in the Administration will condescend to let them do it …”

Zenger was the publisher, not the author, of the critical articles. The authors were anonymous, but history has attributed the articles to James Alexander.

The Governor was furious and determined to have Zenger prosecuted to stop a repeat of those sentiments and in the hope that the identity of the true authors would come to light. Zenger, however, would not betray the identity of the authors.

The Information

Chief Justice De Lancey made two attempts to persuade the Grand Jury to indict Zenger for seditious libel, but on both occasions, unsuccessfully. The Attorney-General then presented an ex officio information for seditious libel, and Chief Justice De Lancey and Justice Phillipse issued a bench warrant for Zenger’s arrest. This was in 1734.

James Alexander and William Smith were retained to act for Zenger, and applied for bail. The evidence was that Zenger was worth £40. Chief Justice De Lancey set bail at £400, plus two sureties of £200 each. Zenger would spend 8 months in prison awaiting trial.

At the arraignment in 1735, James Alexander and William Smith challenged the commissions of the justices of the Supreme Court. That included the ground that the judges were appointed during pleasure. De Lancey CJ adjourned until the next day, where he and Phillipse J held James Alexander and William Smith in contempt and struck their names off the roll of attorneys permitted to practise in the Supreme Court.

Zenger applied to have an attorney appointed to act for him, and the Court appointed John Chambers. He was a newly admitted attorney, and considered sympathetic to the Governor. He was not expected to be very effective. But he surprised everyone. After entering a plea of Not Guilty, he sought a struck jury from the Clerk. The Clerk did not produce the Freeholders’ Book as usual, but produced a list of 48 potential jurors comprised of persons who were not Freeholders but most of whom had, at one time or other, held positions at the pleasure of the Governor. Mr Chambers then applied to the Chief Justice for a struck jury, and De Lancey CJ, probably thinking it would make no difference, ordered the Clerk to draw the jury panel out of the Freeholders’ Book in the presence of the parties, allowing such objections as may be just.

The Trial of Zenger

De Lancey CJ presided at the trial, which took place on 4 August 1735 in Old City Hall (the same building where the first Congress debated what would become known as the Bill of Rights in 1789).

Phillipse J also sat at the trial as second justice.

By the time the matter came on for trial, Zenger’s allies had been able to retain the pre-eminent colonial attorney Andrew Hamilton from Philadelphia. (No relation of Alexander Hamilton). He agreed to act pro bono. After Mr Chambers made his submissions, the appearance of Mr Andrew Hamilton was announced, to the surprise of the Court.

The received wisdom at the time in New York (as well as in England) was that truth was not a defence to seditious libel. All that had to be shown was that the accused authored or published the words, that the alleged innuendo was established, and that the words were in fact libellous. Whether the material was libellous was a matter for the Court to decide, not the jury.[2]

In a master stroke of advocacy, Andrew Hamilton admitted that Zenger had published the words, thereby eliminating the need for the Attorney General to call witnesses who would no doubt have been prejudicial to Zenger. Hamilton then argued that truth was a defence, implicitly admitting the innuendo. He sought to call witnesses of his own to demonstrate the truth of the words, but the Chief Justice denied the request, ruling that truth was not a defence.

Hamilton then proceeded, courageously, to address the jury directly, in a manner which contradicted the ruling of the youthful Chief Justice.[3] He attacked the rule that truth is not a defence; he argued that the rule was inconsistent with the right of freedom of speech; he said the English rule was not applicable in America where the government is the servant of and answerable to the people; he argued that the jury had the power to decide the law as well as the facts; and he appealed to the cause of liberty:

“It is natural, it is a privilege, I will go farther; it is a right, which all free men claim, that they are entitled to complain when they are hurt. They have a right publicly to remonstrate against the abuses of power in the strongest terms, to put their neighbors upon their guard against the craft or open violence of men in authority, and to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty, the value they put upon it, and their resolution at all hazards to preserve it as one of the greatest blessings heaven can bestow…

The question before the Court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern, it is not the cause of a poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying: No! It may in its consequence affect every Freeman that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty … That to which nature and the laws of our country have given us a right – the liberty – both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power … by speaking and writing truth.”

Chief Justice De Lancey instructed the jury that, as publication was admitted, the only matter which should come before them was whether the publication was a libel, which was a matter of law which they may leave to the Court. The summing up, whilst technically leaving the matter to the jury, effectively directed the jury that the publication was libellous.

It did not take long for the jury to return a verdict of not guilty.

The verdict was met with great acclaim in and outside the courtroom.

Reports of the Zenger trial spread throughout America and England.[4] The trial was said to have “made a great noise in the world”.[5] Zenger also published a report of the proceedings in pamphlet form in June 1736, written by James Alexander. It was re-published numerous times as late as 1765 and 1770 and (including in England) in 1784.[6] That report was reprinted in Volume 17 of Howell’s State Trials reports published in England in the early nineteenth century.

There are two main areas in which Zenger’s Case has had an impact: trial by jury; and freedom of speech and of the press.

Trial by Jury

First, Zenger was a stark example of the importance of the jury in providing a constitutional check on executive power. It was an instance of jury nullification – that is where a jury acts contrary to the instructions of the judge as to the law, to prevent an unfair result.

So concerned was King George III about jury nullification that, in the 1765 Stamp Act, violators were exposed to trial in the Vice Admiralty court without juries and which could be held anywhere in the British empire. And British Parliament tried again to undermine trial by jury in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774. By those Acts, Massachusetts county sheriffs (appointed by the Governor) were empowered to appoint juries directly, and the Massachusetts Governor could transfer trials to Great Britain or elsewhere.

It is not surprising then that trial by jury featured in the Declaration of Independence, and was guaranteed by Article III of the Constitution, and in the Sixth and Seventh Amendments.

And, as Sir Owen Dixon recognised, the Australian Constitution was “framed after the pattern of that of the United States”, the framers having studied it with great care.[7]

The reader is invited to consider the similarities between the last paragraph of Article III § 2 of the United States Constitution and s 80 of the Australian Constitution:

“… The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.” (Art III §2)

“The trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury, and every such trial shall be held in the State where the offence was committed, and if the offence was not committed within any State the trial shall be held at such place or places as the Parliament prescribes.” (s 80)

In the writer’s view, it would be wrong to say that the United States Constitution played no role in relation to the inclusion of s 80 in the Australian Constitution.

Freedom of speech/the press

Second, as Professor Levy – the Zenger sceptic – has conceded, “the verdict of history is correct in regarding [Zenger] as a watershed in the evolution of freedom of the press, not because it set a legal precedent, for it set none, but because the jury’s verdict resonated with popular opinion”.[8]

As another commentator put it, “the Zenger case, though it did not directly ensure the freedom of the press, it prefigured that revolution ‘in the hearts and minds of the people’ which was to make an ideal of 1735 an American reality, and it has served repeatedly to remind Americans of the debt free men owe to free speech”.[9]

Because of Zenger, newspapers were emboldened to criticise the policies of King George III; concerns about jury nullification discouraged prosecutions.[10]

In the ensuing years, as the controversy with Great Britain was played out in the press, Zenger was from time to time relied on by those who advocated the right to criticise the policies of King George III and royalist controlled Assemblies.[11]

And though records were not always kept, there are examples of Zenger being mentioned during the debates for ratification of what became known as the Bill of Rights.[12]

Accordingly Zenger led the way for the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press in the United States.

The First Amendment provides:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

In terms of Australian law, the High Court of Australia was aware of the First and Fourteenth Amendments when in the 1990s it recognised an implied freedom of political communication in the Australian Constitution.

At another level, the First and Fourteenth Amendments also played a role in the evolution of the law of sedition.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, it became generally accepted that mere political criticism in good faith and for justifiable ends was not criminal, and truth was relevant evidence for that purpose.

That was the argument made by Alexander Hamilton in People v Croswell, 3 Johns. Cas. 336 (NY 1804), along with the submission that juries were entitled to give a general verdict. That argument was accepted by Chancellor Kent (in the statutory minority). Kent J’s opinion was widely circulated and was acted upon by the New York legislature in 1805[13] and by other States soon after.[14]

However, the writer has found no English case citing Croswell or the New York statute of 1805.

In any event, in 1792, Fox’s Libel Act was enacted in the United Kingdom.[15] By that Act, it was made the province of the jury to give a general verdict of guilt or innocence in criminal libel cases, including whether the offending material was libellous.

Sir Fitzjames Stephen has attributed to Fox’s Libel Act the shift in English law to making malicious intent a necessary element to be shown in seditious libel.[16]

However that may be, it is hard to overlook the significance of the fact that Fox’s Libel Act received Royal Assent on 15 June 1792, a mere matter of months after ratification of the First Amendment on 15 December 1791. The passage of that Amendment must be taken to have been widely known in legal circles in the United Kingdom.

Incidentally, the First Amendment came into force on ratification by the eleventh State, Virginia, whose Constitution allowed truth to be given as a defence and juries to give general verdicts in seditious libel prosecutions.[18]

Then in the year 1899, Sir Samuel Griffith’s Queensland Criminal Code was enacted. This enacted a sedition offence in ss 44-46 and 52 based on the premise that mere political criticism in good faith for justifiable ends was not criminal. For example, it was an offence to use words with the intention of bringing the Sovereign into hatred or contempt or of exciting disaffection against the Sovereign or Government or Constitution of Queensland, unless done in good faith for one or more enumerated purposes, including to endeavour to show that the Sovereign has been mistaken in any of her Counsels or to point out errors or defects in the Government of Queensland.

To like effect, similar sedition offences were provided for in ss 24A to 24D of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), added in 1920,[19] and in Australian Code jurisdictions.

These sedition offences were modelled off the work of Sir Fitzjames Stephen in England.[20] Sir Samuel Griffith adopted Sir Fitzjames Stephen’s Article 93 in his Digest of Criminal Law, 3rd ed 1883 (London: MacMillan) and section 102 of the draft English Criminal Code of 1880 of which Sir Fitzjames Stephen was one of the drafters.[21] But he was fully aware of Zenger’s Case: in 1883, in another publication, Stephen cited Zenger’s Case, describing it as “remarkable”.[22]

The law of sedition has since moved on even further.

The United States Supreme Court eventually (after some roadblocks along the way) came to accept that mere words critical of government cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, be punishable as seditious libel, whether the words were true or not, and whether they were published in good faith or not. Words could amount to sedition, but the speech had to be intended to result in a crime and there had to be a “clear and present danger” that it actually will result in a crime, as held in Schenck v United States in 1919.[23] That test was reformulated in 1969 by the requirement that the words be directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and be likely to incite or produce such action.[24]

Dixon J cited Schenck v United States in his dissent in Burns v Ransley in 1949.[25]

The statutory majority in Burns v Ransley and the majority in another 1949 High Court decision, R v Sharkey,[26] show that Australian law had not at that time advanced to the point reached by the United States Supreme Court. In Burns v Ransley and R v Sharkey, it was held that the offence of sedition under the then Crimes Act 1914 could be committed whenever the accused had an intention to excite disaffection against the government or the Constitution even if there was no intention to excite imminent violence or an illegal act.[27]

However, in 2005, ss 24A to 24D of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) were repealed and replaced with new sedition offences inserted into the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth).[28] These provisions were further amended in 2011.[29]

Under those new provisions, mere words critical of government are not seditious. A person has to, for example, intentionally urge another to overthrow the Constitution or Government by force or violence intending that such force or violence will occur.[30]

The implications of those two 1949 High Court cases remain to be reconsidered in the light of the implied freedom of political communication. This remains a live issue as sections 44-46 and 52 of the Qld Criminal Code are still in force. The common law of sedition applies in non-Code States.

But the present point is that the 2005/2011 Commonwealth amendments were likely influenced by the First and Fourteenth Amendments or at least by the implied freedom of political communication. The Gibbs committee, whose recommendations were adopted in the federal changes in 2005, said that the changes were needed “to accord with a modern democratic society”.[31] Sir Harry Gibbs, who chaired the Commission, would have been aware of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

In any event, the implied freedom of political communication which was discussed in the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee enquiry into the Anti-Terrorism (No 2) Bill 2005.[32]

The Australian Law Reform Commission, in its 2006 report “Fighting Words”, made several references to US law.[33]

Conclusion

At the time the First Congress of the United States debated what would become the Bill of Rights, Governeur Morris, a Founding Father and descendant of Morris CJ, described the Zenger case as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionalized America”.[34]

In the writer’s opinion, the impact of Zenger’s Case is not limited to American law. The ripple effect of Zenger has also been felt in Anglo-Australian law.

[1] The following background and case summary draws on R v Zenger (1735) 17 State Trials 675; and E Moglen, “Considering Zenger: Partisan Politics and the Legal Profession in Provincial New York”, 94 Colum L Rev 1495 (1994). The report in State Trials had been previously published in pamphlet form by Zenger himself, reputed to have been written by James Alexander. That version is available at history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger.

[2] See Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 pp 298-395 (London: MacMillan and Co 1883). See the reference to Zenger at p323 n4. See also “Fighting Words: A Review of Sedition Laws in Australia”, ALRC 104 at pp49-51.

[3] James Alexander is reputed to be the mastermind behind Andrew Hamilton’s argument.

[4] Katz, Introduction to J. Alexander: A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, (S Katz ed 1963) p 26, 30; Alison Olsen, “The Zenger Case Revisited: Satire, Sedition and Political Debate in Eighteenth Century America”, (2000) 35:3 Early American Literature 223, 238; Livingston Rutherford, John Peter Zenger: His Press, His Trial and a Bibliography of Zenger Imprints (1904) p 128; Levy, Emergence of a Free Press, 44 (Ivan R Dee Chicago 1985)

[5] (1735) 17 State Trials 675, at p675.

[6] Olsen, p238; Levy, pp77, 156.

[7] Dixon, “Two Constitutions Compared” in Jesting Pilate (Law Book Co 1965) at p101.

[8] Levy, 37.

[9] Katz, Introduction to J. Alexander: A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, (S Katz ed 1963) p 35.

[10] Alison Olsen, “The Zenger Case Revisited: Satire, Sedition and Political Debate in Eighteenth Century America”, (2000) 35:3 Early American Literature 223; Levy, 17.

[11] Levy, 62, 69, Professor Douglas O. Lindner, “The Trial of John Peter Zenger and the Birth of Freedom of the Press” p8, published in Historians on America, at usinfo.org/zhtw/DOCS/historians-on-america.

[12] Levy, 244, 246.

[13] See Sess. 28, c. 90 (6 April 1805), noted in the report of The People v Croswell, 3 Johns. Cas 337, 411-2 (NY 1804).

[14] Garrison v Louisiana, 379 US 64 (1964) at p 72.

[15] 32 George III, c 60.

[16] Stephen, History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 p359 (1883). As for Australian law, that shift in English law was reflected in the common law received by the Australian colonies: see eg R v Henry Seekamp, Supreme Court of Victoria, unreported, The Argus (Melbourne) 24 January 1855 p4, The Argus 6 February 1855 p5 and The Age 27 March 1855 p5.

[18] Levy, pp211-2.

[19] War Precautions Repeal Act 1920 (Cth), s12, adding ss 24A to 24D to the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth).

[20] See Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101 per Dixon J at p 115; O’Regan, “Sir Samuel Griffith’s Criminal Code” (1991) 14:8 Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal 305, 307.

[21] Section 102 is set out in full in Boucher v The King [1951] SCR 265, 306.

[22] See Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England, vol 2 p 323 n4 (London: MacMillan and Co 1883). Stephen had read the summary of the Zenger trial written allegedly by Alexander Hamilton.

[23] Schenk v United States, 249 US 47 (1919) at p52.

[24] Brandenburg v Ohio, 395 US 444 (1969), replacing the previous “clear and present danger” test articulated by Holmes J in Schenck v United States, 249 US 47 at p52 (1919). It is not necessary to enter the debate about whether the Framers intended the First Amendment to have the operation that it was later interpreted to have.

[25] Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101, at p117, citing Schenk v United States, 249 US 47 at p52.

[26] R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121. R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121

[27] Burns v Ransley (1949) 79 CLR 101; R v Sharkey (1949) 79 CLR 121.

[28] See Schedule 7 of the Anti-Terrorism Act (No.2) 2005 (Cth).

[29] National Security Legislation Amendment Act 2010, Schedule 1, taking effect on 19 September 2011.

[30] Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), Schedule, s 80.2. Similarly, under the post-911 terrorism provisions of the Criminal Code, a person does not engage in a “terrorist act” by mere advocacy if not intended to cause death or serious harm that is physical harm to a person, or to endanger the life of another person or to create a serious risk to the health or safety of a section of the public. Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), Schedule, ss 100.1, 101.1.

[31] H. Gibbs, R. Watson and A Menzies, Review of Commonwealth Criminal Law, Fifth Interim Report (1991) at [32.13].

[32] ALRC 104 at [7.13].

[33] ALRC 104 at [2.36], [6.31], [8.71]-[8.72].

[34] See history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger/

Replica of the printing press used by Zenger, on display at Federal Hall, New York.

Replica of the printing press used by Zenger, on display at Federal Hall, New York.