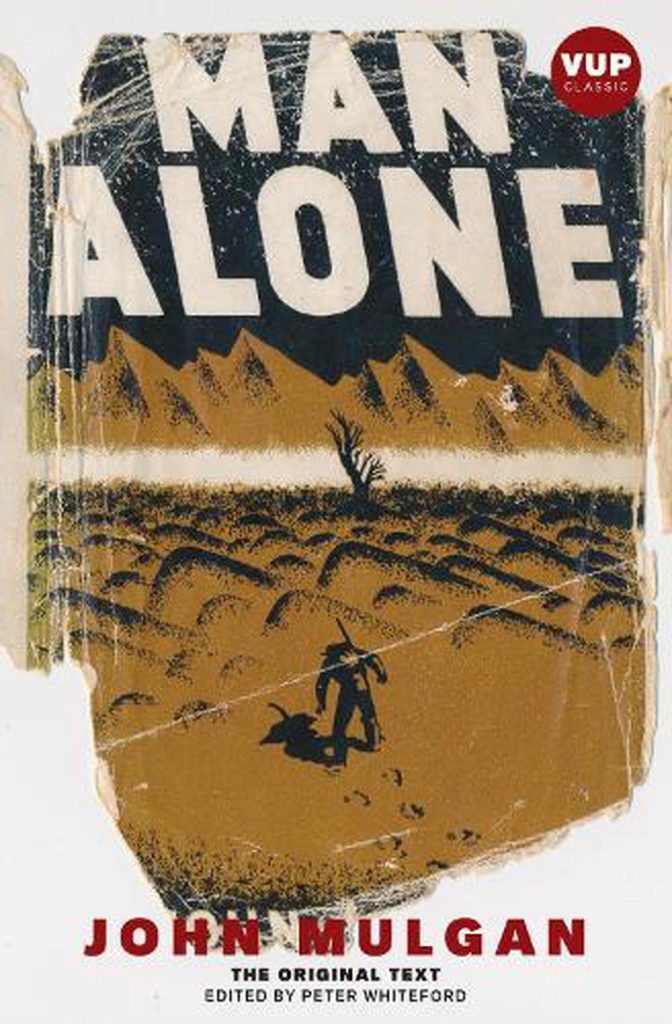

Author (original text): John Mulgan

Editor of this edition (2021): Peter Whiteford

Publisher: Te Herenga Waka University Press[2]

Reviewer: David Marks

Mount Ruapehu is majestic and snow-capped. Silent and godlike, her bulk looms as you arrive in Ohakune.

But travelling the road from Waiouru, you cross a bridge, and come upon the Tangiwai Memorial.

Ruapehu is active. She is dangerous.

The Wellington-Auckland express fell at a rail bridge washed away by a lahar moments before. 151 lives were lost that Christmas Eve, 70 years ago.

Ruapehu.

She, Taranaki, her husband, and Tongariro, her seducer, are more than mountains.

This was plain as we drove into Ohakune in January.

By chance we overnighted there.

We stayed at a trampers’ lodge. We ate at the Powderkeg.

At 1:13am, sirens woke the village. I thought we had bought it.

Ruapehu, lost in darkness and cloud, still loomed, haunting.

Sirens are how the village turns out its volunteer fire brigade.

But we were strangers in a strange land. We did not know that, at 1:13am in the shadow of Ruapehu.

Ruapehu is always there during the climatic incidents of John Mulgan’s only novel, Man Alone.

The ‘great New Zealand novel’, Man Alone, is a canvass on which thousands have projected their thoughts.

Having sampled this literary output, I wondered if we were all reading the same book.

Contrary to one paper I read, the novel is no apology for ideology. Whatever the actions of the hungry and desperate characters depicted, the main protagonist is driven by pragmatism, not ideology, even in the end. He keeps moving, remaking himself.

More substantially, does Mulgan project part of the Maori legend of the three volcanoes on to the lives of these common folk? It is all up for grabs.

Canvass or mirror? No analogy explains how Mulgan’s sparse prose about plain-spoken folk captivates a nation.

Great art reflects more than the light that falls.

Spare, Mulgan’s prose is unstoppable.

You cannot put this down. The Ancient Mariner has begun his tale. Is there redemption?

Mulgan’s protagonist encounters ordinary people, and works hard at simple work. He can milk, strain a fence, clear a yard, and make a road.

This sounds unpromising material.

Yet, the protagonist stands above and outside. Perhaps, he is indestructible. He is flawed like all of us. He accepts this and still moves forward.

Why is there no movie? Once were Warriors & Whale Rider also hold standing as great New Zealand novels, filmed.

It would take the best director in the moody French tradition to render Man Alone’s interior monologue a film.

Time slows between the two World Wars.

Occasional references, to time that has passed, surprise. Mulgan has to remind us that time has passed, in the drear and mud of hard work.

The economic calamity between the Wars drives men and women to despair. Sometimes they err.

There are no excuses. At least – there are no excuses that stick or are worth tuppence.

Actions have consequences. Consequences follow regardless of time and space.

Mulgan’s protagonist is driven up the slopes of Ruapehu, across the Rangipo Desert, and into starvation in the wilderness further East.

In January we drove up the Desert Road, built after Man Alone was published. A stranger does not drive this stretch of ‘State Highway 1’ without local advice. We found a lonely stretch, with a lone traffic cop tolling the careless. You know you are entering upon danger. The road is guarded by gates as you leave Waiouru. They close in Winter, for the ice and snow.

Mulgan takes us there, before this civilising road. There is tussock and a lonely coach track. And then bush on the other side.

There is some redemption in the wilderness, for our Everyman protagonist.

But consequences dog him regardless of apparent escape.

-oOo-

I started reading an older edition. Don’t.

Peter Whiteford has lovingly restored Mulgan’s text, and I should think the VUP edition will become the scholarly edition, and the edition favoured by us common readers.

Mulgan did not live to see the success and acclaim of this novel. Published in England in 1939, the novel risked loss. The plates were destroyed in war. Mulgan died by his own hand in Cairo in 1945, after distinguished service behind the lines in hostile Greece. He was not there to press his novel’s cause in the peace.

When the gravity of this potential loss was later appreciated, Mulgan’s words were inexplicably altered by new, well-meaning publishers.

Whiteford has now restored Mulgan’s intent, as close as can be divined.

But every great work needs its back-story, its mystery, and perhaps some tragedy.

So, here.

I came upon this novel because of the recent VUP book by Gounelas and Parkin-Gounelas, John Mulgan and the Greek Left: A Regrettably Intimate Acquaintance (2023).

But that is another story.

(David is an Australian barrister who keeps close tabs on affairs in New Zealand.)

[1] ISBN 9781776564156

[2] Formerly Victoria University Press