Author: Jeremy Gans

Publisher: Waterside Press

Reviewer: Franklin Richards

The Ouija Board Jurors is a mystery, a history, an exposé and an exploration. Jeremy Gans, a Professor at Melbourne Law School, uses the& 1994 murder trial, R v Young, as a prism through which to critique the jury system. His work explores in detail how the jury system, initially, faltered but, ultimately, succeeded in delivering justice in this troubling case. The process exposed vulnerabilities in the jury system and the law and brought into focus the particular pressures endured by jurors.

The story begins, as do so many legal stories, with tragedy. ‘Flash’ Harry Fuller, an Arthur Daley type businessman and his new (third) wife, Nicola, are killed in their cottage in Wadhurst, a village in Sussex, England. Harry was shot through the heart downstairs and Nicola shot several times in the head, in their upstairs bedroom. The fatal last shot was fired through a duvet as she lay wounded, speaking to a 999 emergency services call operator.

Suspicion eventually settled upon Steven Young who would face three trials, the first aborted, the second and third delivering guilty verdicts. It is the second trial that is Gans’ subject.

The evidence implicating Steven Young was strong. He had motive, means and opportunity. Young, an insurance broker from Pembury, another small town, was in financial difficulties and had arranged to meet Fuller on the day of the murders and paid some of his debts in cash, the day after. Crucially, Young had a secret arsenal and the bullets found at the crime scene were linked to ammunition and reloading equipment found at his home. Still, in many respects, he was an unlikely killer: family man and active and respected community member.

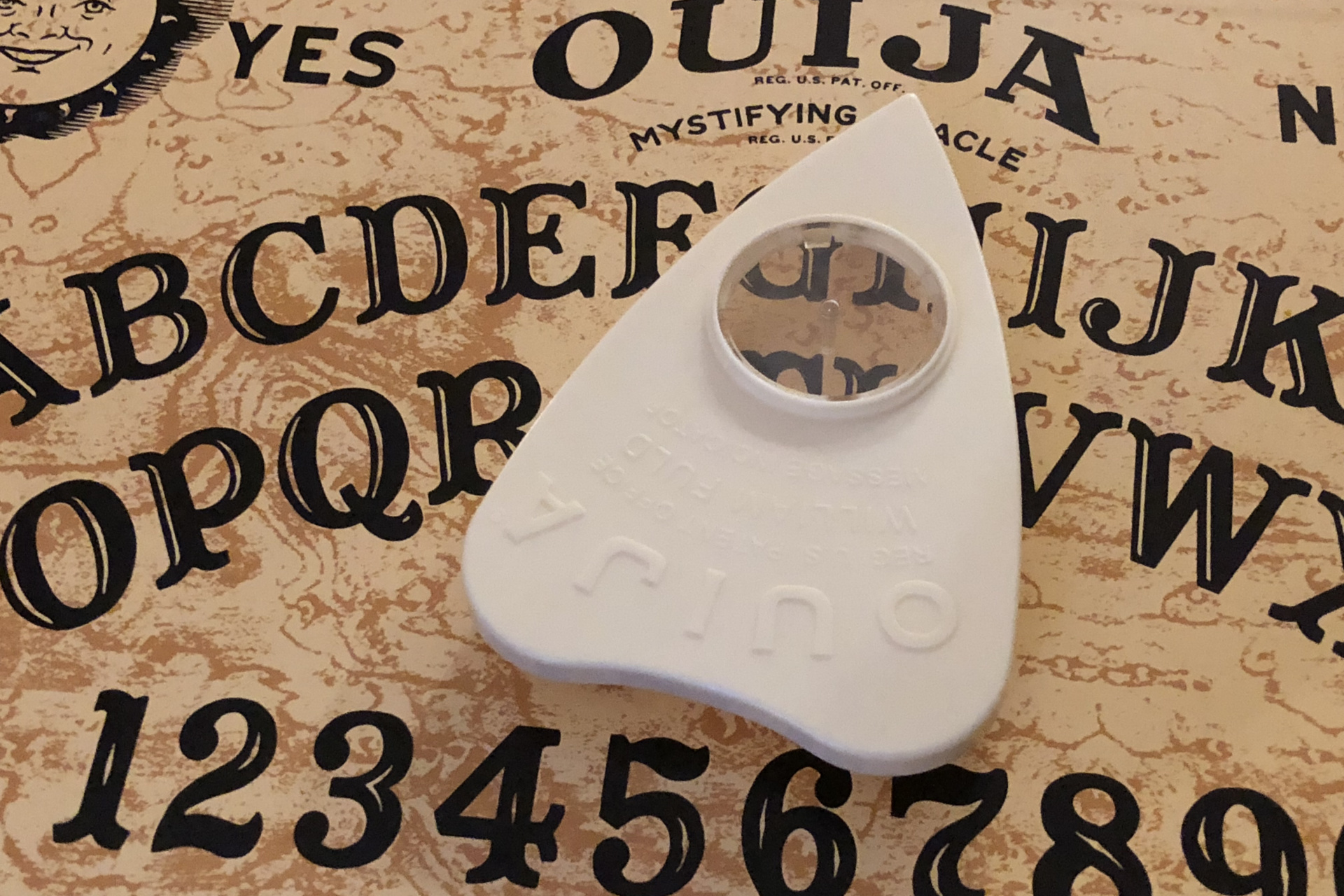

The task of deciding the matter could not have been easy, particularly, given the nature of the evidence, including the 999 emergency call recording Nicola’s garbled last words and the shot that killed her. Deliberations exceeded one day and the jury were locked up overnight at The Old Ship, a Brighton seafront hotel. So it was that four jury members had a few drinks, fashioned a makeshift Ouija Board and sought guidance from dead Harry Fuller. The whole affair might have remained secret had it not been for a fifth jury member writing to the News of the World to express his disquiet about the episode and the verdict.

Gans describes the judiciary’s discomfort and ruminations that followed the revelation, and the appeal process that finally ordered a new trial. The task facing the Court of Appeal was complex and two troubling questions resonated: how was the matter to be investigated and on what basis should the appeal be decided? In the end, the Treasury Solicitor would supervise the investigation into what had happened at The Old Ship. And the question to be decided was whether there had been a ‘material irregularity’ rather than whether the jury got the verdict wrong.

Resolving the relevant issue left counsel struggling for guidance from past cases. One Court of Appeal case from the previous year concerned a juror making a mobile phone call from the jury room. The call was ongoing but solely business related and no ‘material irregularity’ was identified. But what of a ‘call’ made by a few tipsy jurors, to a deceased victim, seeking guidance about the facts of the matter? Finally, and not much assisted by precedent, the Court found ‘material irregularity’, quashed Young’s convictions and ordered a new trial.

Gans has a charming sense of humour that he occasionally exercises in his otherwise sober discourse. For example, he gives a history of spiritualism and the Ouija Board, lamenting the Court of Appeal’s too brief treatment of the subject.

‘The history of Ouija boards, a topic almost entirely neglected in the Court of Appeal’s judgement, commences with the growth in spiritualism among middle-class and upper-class Americans in the mid-19th-century, in part as a response to civil war casualties … The Court of Appeal’s account never mentions that the 1994 owner of the trademark ‘Ouija’ was a familiar name, Parker Brothers, best known for Monopoly, Cluedo, Risk and Trivial Pursuit.’

Gans also has an eye for the absurd, canvasing the myriad ways jury conduct has gone awry over the years and how various jurisdictions have dealt with it. In one such case, a Colorado jury decided not just guilt but also settled upon the death penalty for a rapist and murderer. On appeal, it came to light that a juror brought a bible to deliberations in order to ‘show Jesus the scriptures I had looked up’. Gans mischievously explains, ‘The “Jesus” to whom she showed the passages was not the Christian Messiah but rather a fellow juror, Jesus Cordova.’ The scriptures ‘looked up’ were Leviticus 24:20-21: ‘fracture-for-fracture, eye-for-eye, tooth-for-tooth … whoever kills a man must be put to death.’ The death penalty was belatedly, but not too belatedly, commuted to something less final.

At the heart of this book is Gans’ consideration of the heavy burden carried by jurors in criminal trials: deciding facts and, ultimately, the question of guilt, based upon the evidence before them. It is a very big task and it takes a toll.

In this context, & Gans references Modern Times, a BBC documentary that included recollections of anonymous jurors. A juror from Steven Young’s third and last trial recalled the end of one distressing day: ‘The journey home on the train was very quiet. Very quiet. It just … I didn’t read…I didn’t say …I didn’t think but just one thought was on my mind and you couldn’t think of anything else. Nothing was allowed in, you know, it was …just … you went over and over and over again …’ At home, he showered and shivered in a room his wife found too hot. Later, he drank to forget and to sleep. ‘It worked,’ he said.

In the end, Gans concludes that trial by jury is imperfect, not that the system is hopelessly unworkable or should be replaced. The lesson of this case is that a juror’s task is hard and often thankless, and that this fundamentally important system can be improved. Of the Ouija Board Jurors, Gans writes, ‘Not only should we be prepared to approach their seemingly outlandish behaviour with sympathy but we should always ask: what might we have done if we had to bear their burden?’