The Blokes Book Club has a new member, Damien, a creative type working for “a Brisbane-based multimedia, web design, print services company”. That’s what its website says, anyway. It wasn’t Damien, however, who came up with William Gibson’s first novel, Neuromancer, as our reading task for the month of August. Sci-fi is a secret love of Andrew, engineer and amateur historian of railway bridges and other transport infrastructure. And it was to Andrew’s impeccable, fifteen year old, workers’ cottage to which we trooped to discuss, as part of a wide ranging and rambling discourse, the inner workings of Neuromancer.

As a matter of pure coincidence, Damien also happens to love sci-fi and has read every one of William Gibson’s nine novels.

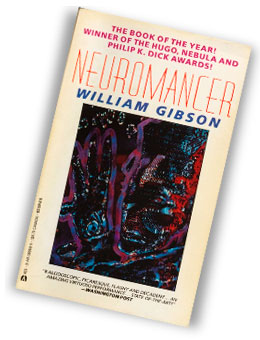

Neuromancer was published in 1984. As with much science fiction writing, the first few lines of Neuromancer sound old fashioned, almost like a two shilling western and then the narrative takes hold.

Case is a former cowboy of the Matrix, the complex of data that allows disembodied travel. He works for criminals who steal from corporations via the Matrix; had been taught by the geniuses of his trade; and was respected for his brilliance. Case is a criminal super hacker imagined before there were things to hack and hacking had become a reality. But he took his ultimate fall. He kept something of his ill-gotten gains back from his employers and was caught trying to flog it off in a black market in Amsterdam. His punishment was not death as he had expected. It was subtle damage to his nervous system which prevented him from having any further ability to ride the Matrix. He was unemployed and unemployable.

The novel opens in Chiba, Tokyo’s port, in a nether world of down market criminality, where Case is making dangerous deals and spending his dwindling supplies of New Yen on a fruitless effort to find a cure for his damaged nervous system. Case is aware that he is one careless error away from oblivion and subconsciously looks forward to the end.

The one matter that complicates his acceptance of his anticipated violent end is his relationship with Linda Lee, another lost soul, whose love for Case is matched only by her physical addiction to the various amphetamine like drugs to which Case has introduced her during their short relationship.

Case’s life, without any effort on his part, takes a dramatic change. He is kidnapped by the beautiful and physically enhanced Molly on behalf of a former war hero, Armitage, and offered an opportunity of the kind that one does not refuse even if one could. He is offered medical restoration of his former capabilities in order to work solely for the principals behind Armitage. The restoration works although Case is informed that, were he fail to continue to cooperate, tiny poison sacs implanted in his body would reduce him to his former state of nervous system disadvantage in short order.

And, so the adventure begins. Molly’s physical enhancements add to her physical prowess and include modifications to assist her role as muscle for her employers. They include blades attached to and recessed into her fingertips. In addition, her vision and perception are also enhanced by microchip inserts.

Molly and Case become lovers as well as colleagues and they work together to find out who lies behind Armitage. The answer turns out to be a form of artificial intelligence called Wintermute associated with a corporate giant, Tessier-Ashpool, whose ventures include a tourist oriented satellite in space called Straylight, a sort of extra-terrestrial cross between Atlantic City and Las Vegas. What is not clear is why Wintermute’s actions and intentions do not seem aligned with the interests of the corporation to which it belongs and who has programmed it and, initially, created it. What is also unclear and of considerable importance is whether Wintermute is, ultimately, a force for good or evil, notwithstanding, case’s limited ability to control his options.

The imagination displayed by Gibson in a book written before 1985 is very striking. His anticipated of a fully-fledged internet under the rubric of the Matrix is very impressive. His depiction of corporate internet security able to be visualised as similar to a vaporous form of ice and its ability to cause damage to any disembodied traveller who approaches too near is both imaginative and impressively predictive of the various anti-viral and anti-hacking devices that are continually developed to protect computers and information, today.

It is a Chinese military device that Case uses to defeat the Tessier-Ashpool ice. Slowly but effectively, the Chinese device engages with the ice and takes it in an embrace that renders it powerless to stop Case’s virtual intrusions. As a metaphor, that piece of inventiveness has gained further kudos as Chinese military hacking has become an increasing problem.

Neuromancer is a brilliant piece of predictive imagining. Its credentials as a classic of science fiction are not to be doubted. Good fiction of any kind, however, requires good characters and Gibson provides an excellent cast from what one might have thought were dubious ingredients. Molly is an avenger for the exploited and the down trodden. Case obtains a moral view of the universe despite his criminal background and his willingness to kill or be killed. And Wintermute, although its primary importance may be as a vision of artificial intelligence whose day is still to come, displays a quirkiness and impishness of which any writer of fiction might well be proud.

The relationship between Molly and Case is in many ways one of convenience. It is also one of subtlety, tenderness and an equitable sharing of teaching, learning and initiative. The relationship between Case and Linda Lee appears to have finished in an unfortunate bout of blood spilling in the mean streets of Chiba. Later in the novel, however, at the behest of Wintermute, there is a sequel which bestows the relationship with longing and significance that surprises Case as much as it does the reader.

The Blokes were divided about Neuromancer. John, the consultant town planner, who understands everything claimed to be still coming to terms with the book’s language and concepts. Damien gave us a potted history of the emergence and career of Gibson and was fulsome in his praise. Others were still undecided. Andrew, who suggested it, was reading Neuromancer for the second time in a few months. Andrew’s idea is not as crazy as it sounds in a world of too many books and too little time. Neuromancer is definitely a book where much that was skimmed over in a first reading is understood at further levels and gains significance on a second look.

I loved Neuromancer. The prediction of the internet and hacking and several other technological changes that have since become reality was impressive enough. What made it an excellent novel, however, for me was the relationship stuff.

The melancholy and longing of a good love story gets me every time.