Background

The litigation between two traders in the natural medicine field had been raging since 2001. The central question was whether the trade mark of the applicant (Health World), ‘Inner Health Plus’, which claimed a priority as a common law (or unregistered) trade mark, was deceptively similar to the registered trade mark ‘HealthPlus’ owned by the respondent (Shin-Sun).

There were three applications before the court. Two by Health World for the removal of the HealthPlus trade mark from the register and the third by Shin-Sun for restriction of the Inner Health Plus trade mark which was subsequently registered, to specific probiotic capsules.

Although several grounds entitling the removal were made out, the linchpin to such entitlement was Health World’s standing to make a complaint under s 88 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). As all three proceedings had been commenced prior to the commencement of the Trade Marks Amendment Act 2006, the provisions of the Act applied as they stood prior to the 2006 amendments: (the primary judge at [31])

Health World therefore had to show it was a ‘aggrieved person’, both for the purpose of s 88 and for its second application, the non-use application under s 92(1) and (3) of the Act, which required the ‘aggrieved person’ standing before the amendments.

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of:

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of:

- what constitutes an ‘aggrieved person’ for the purposes of s 88; and

- the circumstances when the Court might exercise discretion not to expunge the mark from the register under the discretion contained within s 88 or s 89,

are instructional but not the focus of this short comment. The observation made by this paper concerns the likely revocation of the Shin-Sun trade mark but for the lack of standing issue of Health World.

The Issue

If Health World had had standing, it would have succeeded on the following:

- The s 59 ground: Health World claimed that Shin-Sun did not intend to use or authorise the use of the HealthPlus trade mark in relation to the goods specified in the trade mark application: (reasons of the primary judge at [15] and [174]);

- The s 88(2)(c) ground: which provides that rectification may be sought on the ground that, by reason of the circumstances applying at the time of the application for rectification, the use of the registered trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion: (reasons of the primary judge at [18] and [182]).

The circumstances which gave rise to these findings are not uncommon. Shin-Sun was incorporated in 1993. Its directors were Mr James Shin and his wife, Mrs Anna Shin. Mr and Mrs Shin were the sole shareholders. Ms Theresa Shin was the general manager of Shin-Sun. She was the daughter of Mr James Shin and Mrs Anna Shin.

Nature’s Hive Pty Ltd was incorporated in 1995. Mr and Mrs Shin were also the directors of that company and Ms Theresa Shin owned twenty of the twenty-one issued shares. Her uncle owned the remaining share.

Ms Shin described the companies Shin-Sun and Nature’s Hive as family businesses, managed principally by her and her parents. In summary, Ms Shin was the General Manager of both companies but they had different shareholders: (the reasons at [60] — [66]).

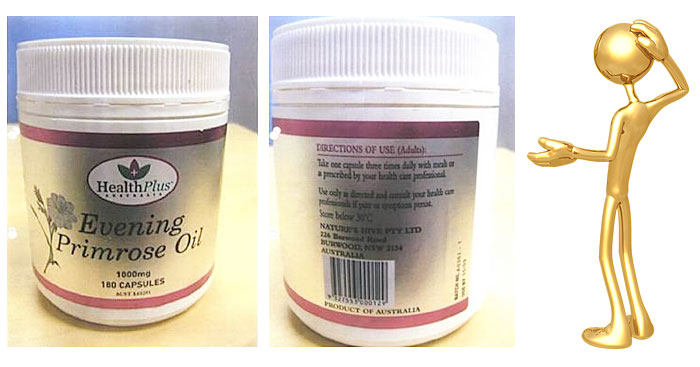

Shin-Sun was the owner of the trade mark Health Plus, however it was Nature’s Hive who manufactured the natural medicines which were sold under the trade mark Health Plus. Further, the name and details on the bottles, was that of Nature’s Hive.2 His Honour therefore noted at [179]:

…at the date of the commencement of the rectification proceedings, the HealthPlus trade mark was used to identify the goods as those of Nature’s Hive, and not those of Shin-Sun…This would give rise to the likelihood of deception or cause confusion because of the failure to identify the registered owner as the source of the goods.

Trade mark law rests upon the ability of a trader to distinguish his or her goods or services from another trader by means of a ‘sign’. The failure of Shin-Sun to associate itself, the trade mark owner, with the goods would have been fatal to the mark. No doubt in the minds of the family, there was no difference between the manufacturer and the trade mark owner, however as noted by his Honour in relation to the evidence of Ms Shin at [171]:

the overall effect of her evidence was that she failed to distinguish between the two separate corporate entities, Shin-Sun and Nature’s Hive. I cannot be satisfied, and I find that she did not pay attention to which corporation she was representing when she took the steps that she relies upon to support the assertion that Shin-Sun intended to use the mark.

In my opinion, Shin-Sun has failed to discharge the evidentiary onus of satisfying the Court that it had a sufficiently clear and definite intention that Shin-Sun proposed to use the mark on goods within class 5 so as to establish a connection in the course of trade between Shin-Sun and the goods.

Isolated instance?

Isolated instance?

The impression appears to be that there may be an inclination to depart from the original purposes in setting up some commercialisation structures by virtue of the level of informality of the operators. Similarly in a recent case,3 Collier J concluded that the opposition succeeded on the s 59 ground, that there was no intention to use the mark in suit.

The basis of her Honour’s finding stemmed from the unclear ownership position of the trade mark in suit. This position was in large measure caused by the interchangeability of roles between the various corporate persona of one person, Mr Lawrence. That did not present a problem when the question of authorised use was considered, as her Honour concluded at [77]:

The evidence before me is that Mr Lawrence tended to confuse his own business interests with those of his companies, and appeared to randomly use companies and trade marks depending on the circumstances. In this respect I consider that it is open on the facts to find that all companies controlled by Mr Lawrence were authorised to use trade mark 967804.

Collier J was clear however, that the basis of the entitlement to lodge an application for a trade mark was ownership, not use, and ownership in this case was impossible to determine on the evidence: (her Honour’s reasons at [92]).

Conclusion

I would suggest that these cases highlight the need to establish clearly:

- Who owns the mark;

- What connection is made in the eyes of the public between the owner and the mark;

- The role of authorised users of the mark.

In this regard, although documented licence agreements will not cure substantive defects, they provide a helpful tool, guideline and starting point for trade mark owners and users as to the requirements on standing relevant to enforcement.

Dimitrios Eliades

Footnotes

- Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 100 (Jacobson J) (Healthworld); upheld on appeal in Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 14 (Emmett, Besanko and Perram JJ): found at http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/FCA/2008/100.html

- See example of the Shin-Sun trade mark and product below.

- Television Food Network, G.P. v Food Channel Network Pty Ltd (No 2) [2009] FCA 271 (Collier J, 27 March 2009)

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

You are invited to dicsusion your opinions on this article in the Hearsay Forum …

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of:

The reasons of Jacobson J (upheld unanimously on appeal) on the questions of: